When then-University President Lloyd Elliott announced that GW would not divest from companies tied to South Africa in April 1986, he had engaged in months of forums about divestment with the Student Government Association, Faculty Senate and other stakeholders.

Now, almost 40 years later, student protesters at GW and across the country have a similar demand — divest from all companies with ties to Israel, as the country’s government continues a military assault on the Gaza Strip following Hamas’ attack on Israel in October. GW has since similarly maintained that they won’t divest.

But this time, officials have kept their decision-making process on rejecting divestment from companies that provide arms to Israel more private, to the chagrin of faculty and students who call for more financial transparency.

University President Ellen Granberg, Provost Chris Bracey, Chief Financial Officer Bruno Fernandes and Dean of Students Colette Coleman invited seven pro-Palestinian student organizations to a meeting in May, two days after local police arrested 33 pro-Palestinian demonstrators after encamping in University Yard to protest Israel’s war in Gaza. Officials said they planned to discuss issues raised during protests like free speech and Islamophobia on campus but will not consider changes to its endowment investment strategy, academic partnerships or student conduct processes.

Pro-Palestinian protesters have since met with University officials several times to discuss their disclosure and divestment demands, but earlier this month, students said they “walked away” from their fourth meeting after determining the talks wouldn’t result in “material outcomes.” Students met with two Office of the Provost officials, who said they had only been involved with discussions about the protesters’ demands “for a few days.”

Fernandes said GW does not support divestment or academic boycotts against Israel, which is consistent with the University’s “long-standing position” on the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement to Israel, but said the mix of investments in GW’s endowment — a financial foundation used to fund professorships, scholarships and construction projects largely from donations — are “fluid” and change to maximize returns in line with GW’s investment policy, which is approved by the Board of Trustees.

He said endowment investments include an array of “complex funds across multiple asset classes” through GW’s investment manager, the Strategic Investment Group.

“GW is contractually barred from providing specific details about these funds in order to maintain a competitive market advantage, consistent with our fiduciary obligations to fund the academic enterprise,” Fernandes said in an email.

The investment firm offers a framework for divestment, noting that they can build “mission-sensitive portfolios,” according to SIG’s Socially Responsible Investing with Hedge Funds packet. SIG is currently aiding GW’s divestment from the fossil fuel industry.

Granberg said last week that it is “virtually impossible” to divest from a specific industry, which trustees and officials realized over the last five years amid GW’s ongoing fossil fuel divestment. She said the way universities invest in companies has changed “so much” in recent years, but when asked why, she deferred to Fernandes, who then declined to say how investments have changed.

“I’m actually going to have to punt based on ignorance, because I don’t want to act like I know,” Granberg said last week.

Fernandes said officials have been working to provide “more and better” information about the University’s endowment. After calls for investment disclosure, officials launched a website last week displaying the University’s publicly available financial documents, containing nine categories of financial data for fiscal year 2023 — including endowment growth, philanthropy and operating expenses — and financial reports for the last five fiscal years.

The website does not include details about GW’s specific investments but does include the breakdown of which sectors of GW’s endowment have grown in the last 10 years.

The University’s current communication on its divestment decision-making differs from past divestment movements, in which top officials demonstrated more of a willingness to discuss specifics and explain GW’s approach to investments.

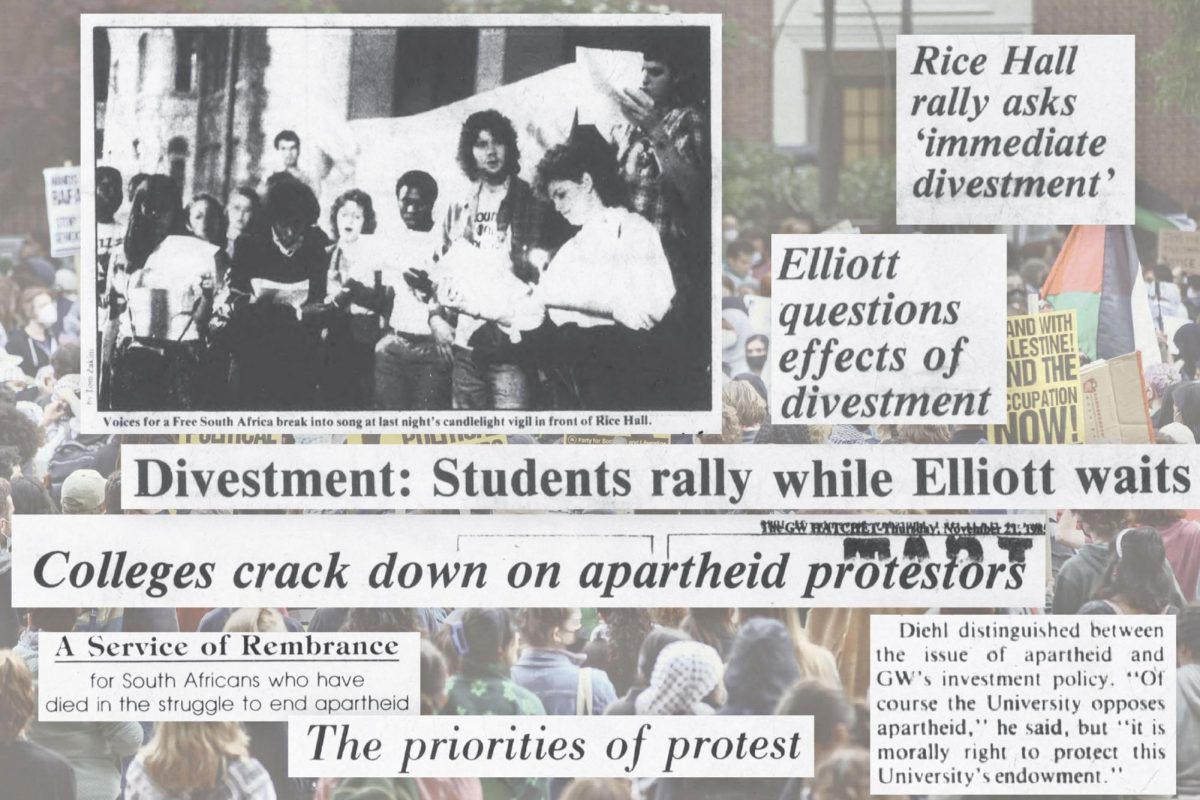

In 1985, a coalition of students who dubbed themselves GW Voices for a Free South Africa set up a campaign to pressure University leadership to pull its investments in apartheid — a government-enforced system of institutionalized racial segregation against the country’s nonwhite majority that lasted from 1948 to the early 1990s.

Students spent the year setting up protests on campus and vigils outside administrators’ offices to bring attention to the issue, garnering support from other students who agreed it was unjustifiable for the University’s endowment to include funds from companies that aided South Africa’s segregation and discrimination tactics.

“No progress can be made until every last vestige of apartheid is removed,” GW Voices for a Free South Africa member David Goldstein shouted at a campus candlelight vigil in November 1985.

Elliott “seriously considered” moving the University’s stock portfolio to a South Africa-free fund beginning in June 1985, according to a 2020 research article detailing GW’s divestment history by alum Andrew Novak, which synthesized University and Hatchet archives.

Trustees had already expressed a “strong and continuing opposition” to apartheid in 1978 and committed that year to only invest in companies that subscribed to the Sullivan Principles, which required companies working in South Africa to desegregate their workforce and enforce equal pay.

A letter from Elliott to then-University Vice President and Treasurer Charles Diehl in 1985 shows that the former University president asked him to research the corporations that GW held stock in and determine which ones had not subscribed to the Sullivan Principles. In September 1985, Diehl set up a meeting with representatives from the Commonfund investment firm, which at the time managed the University’s endowment to discuss what divestment would look like for the University.

But before the meeting, officials called a forum with community leaders to discuss how the University should respond to apartheid.

“President Lloyd Elliott and Vice-Presidents Diehl and William Smith called a meeting last Friday morning with student representatives and active members of GW Voices For a Free South Africa to discuss GW’s most effective response to the South African policy of apartheid,” reads a Hatchet article from September 1985.

In the meeting between students and officials, Diehl pledged to seek a quote from a South Africa-free fund as to investment performance and risk. Then-SGA President Ira Gubernick said officials discussed a timetable for complete divestment, adding that it was a “damn good” start.

During Diehl’s later meeting with the fund’s representatives, they said they could arrange a South Africa free portfolio but refused to manage it because removing large corporations like IBM and Exxon — which were subscribed to the Sullivan Principles — made the risk “too great.” Diehl said it would cost the University between $300 million to $500 million to create the fund and hire enough managers.

Ultimately, he told Elliott that it was “morally right” for GW to protect the University’s finances and advised him not to divest.

In a forum with 50 students, Elliott announced that divestment was not the best response to apartheid because GW would lose influence over the corporations doing business there, and any economic contraction would harm the majority of South Africa’s population, prompting students to ask him questions on the decision.

During the meeting, Elliott said trustees and the University could be sued by GW’s donors if any University investment policy lost money because they’d be failing to meet their “fiduciary duty,” which they were legally obliged to follow.

“To fail to manage [the funds] so as to meet its fiduciary duty as prescribed by law would be a betrayal of the responsibility of the governing board and could be counted on to bring prompt legal channel by donors, their descendants and by potential beneficiaries,” Elliott said at the meeting.

At the time, SGA Vice President Tom Fitzpatrick called Elliott ‘‘remarkably forward” surrounding his openness to discuss divestment with students.

“We were sad and upset and frustrated,” Goldstein, who was a sophomore at the time, said in July. “We thought we had made a good case why the University should have divested from South Africa and how it wouldn’t hurt the University financially. But I vaguely remember there was real concern about the University removing money from the fund, and it would hurt the endowment.”

Novak, an associate professor of criminology at George Mason University, said GW, like other universities, operates like a corporation and is overseen by trustees who have a “fiduciary duty” to earn profit from the endowment and to earn it to the largest extent possible, as long as it remains consistent with the University’s mission.

The mission statement says GW should work to educate individuals in sectors like liberal arts, languages, sciences and other courses of study to conduct research and publish their findings. Trustees shortened the statement in 2019, eliminating a part that touched on “furthering human well-being” due to it being too “broad and expansive.”

The Board’s Committee on Finance and Investments oversees GW’s financial and business affairs, including exercising oversight and governance over the University’s endowment with the goal of “enhancing returns and purchasing power from investments while preserving resources for future generations,” according to its mission statement.

Novak said for GW to divest, activists need to convince trustees that investing in companies that do business in Israel does not align to the University mission, which he said is “hard to do” because the mission is “vaguely worded.”

“If you don’t convince them of that, then they have to invest in the way that is the most profitable, that they have a duty to,” Novak said.