Community members said they are skeptical of the University’s pledge to divest from fossil fuels by 2025 due to a lack of communication from officials, who maintain that they are on track to reach their goal.

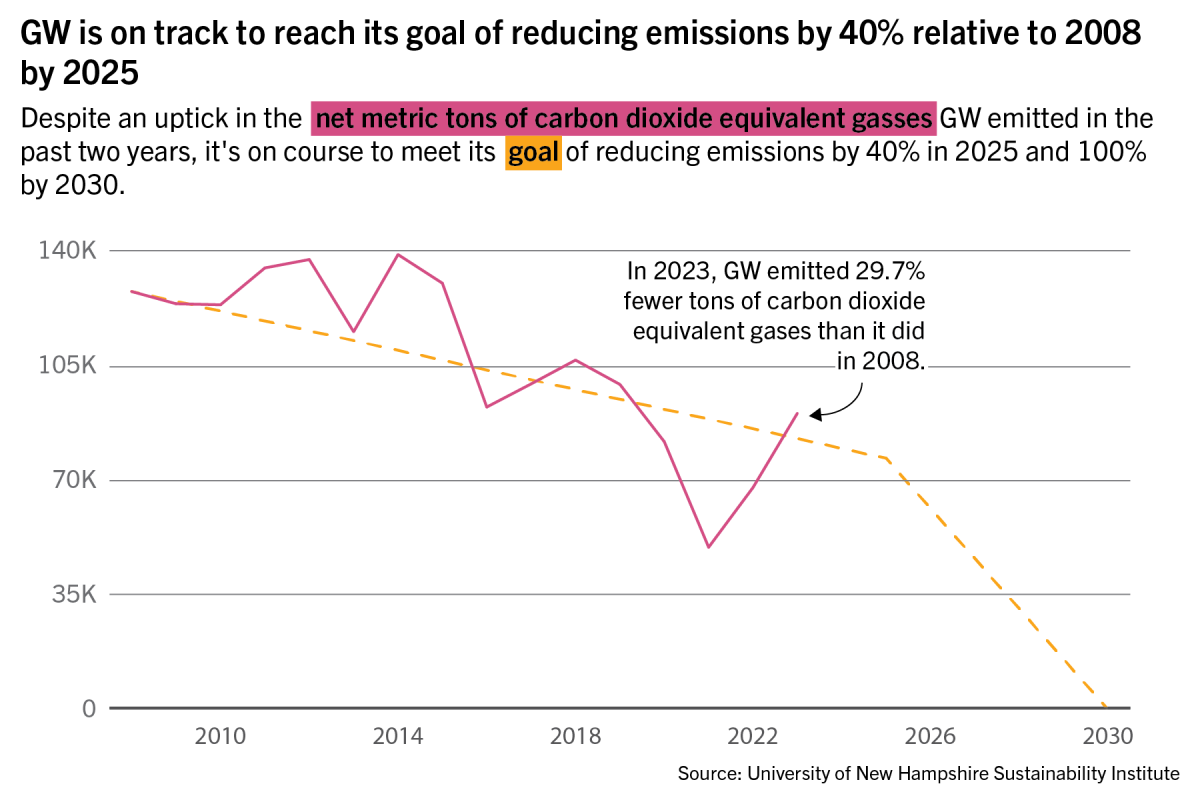

GW reduced its emissions by 29 percent between 2008 to 2023, according to the University’s public emissions report, leaving the University with two more years to lower emissions by an additional 11 percent to hit its target of 40 percent by the end of next year. After almost a decade of student protests for fossil fuel divestment, the Board of Trustees in 2020 established the Environmental, Social & Governance, Responsibility Task Force and adopted environmental recommendations from the group that included total divestment, lowering emissions and a 10-year acceleration of GW’s initial plan to reach carbon neutrality by 2040.

GW Office of Sustainability Director Josh Lasky said the University has a “multi-pronged strategy” to meet its emission reduction goal by next year, with an emphasis on energy efficiency on campus and the administration’s renewable energy development and sourcing. He said officials are currently working to to reduce the University’s energy consumption through lighting, heating and cooling in 43 campus buildings.

Lasky said officials are also developing a “decarbonization plan” to modernize building systems and reduce GW’s carbon footprint but did not specify what the plan would entail, who is developing it or whether officials think the University is on track to become carbon-neutral by 2030.

“GW is on track to meet the interim 40% reduction target by 2025,” Lasky said in an email.

Officials said in May 2023 that GW’s investment in companies that earn a majority of their revenue from burning fossil fuels dropped from roughly 3 percent in 2020 to under 2 percent. Lasky deferred comment on any additional steps officials have taken toward divestment to an April 2023 release, which states that GW worked with a fund manager to create a “fossil fuel free strategy” and invested with a fund manager that will transition remaining holdings.

Lasky said GW is working with an adviser to create a “sustainable transportation strategy” for the Mount Vernon Express, which includes transitioning to electric vehicles, Lasky said. He said the University has already begun to transition the shuttles to liquid propane gas, which reduces emissions by 25 percent compared to diesel vans.

Officials are steadfast in their verbal commitment to the environmental targets, but members of the ESG task force said the University has lacked communication about its progress toward implementing their recommendations.

Jeremy Liskar, a former graduate student and member of the ESG task force, said he would have liked to see more updates on GW’s progress toward sustainability. Liskar said when the ESG task force’s recommendations were adopted by the Board, which included a promise of updates on the University’s progress toward divestment, the task force was notified.

Liskar said the 2020 update was the most recent update he heard.

“There really wasn’t much transparency or follow-up at all,” he said.

Melani McAlister, a professor of American studies and international affairs and a member of the ESG task force, said she hasn’t heard details from officials about how they plan to achieve emissions and divestment benchmarks since their initial commitment to do so in 2020.

“We need to be hearing about that from our leadership, what we can do, what they’re doing, how things are going to change, and I know we just simply don’t,” McAlister said. “I don’t see that kind of messaging when I’m on campus. I don’t get the lessons and how these old buildings that we have are going to be changed.”

She said because the University took 15 years to cut 29 percent of its emissions, she is skeptical that officials will reach their pledge of a 40 percent reduction in the next two years.

“I’d have to see something pretty dramatic, and I haven’t seen it,” McAlister said.

The largest contributor to the 29 percent drop in emissions is the University’s purchased electricity, which shrunk from 74,980 tonnes of carbon dioxide in 2008 to 14,270 tonnes in 2023, according to GW’s public emissions report. About 60 percent of the University’s energy use is obtained through renewable sources, according to the Office of Sustainability’s website.

Lasky said GW has approved the installation of solar panels on more than a dozen rooftops on the Foggy Bottom Campus, including Francis Scott Key, Lerner, Guthridge, South, Stockton, Science and Engineering and Rome halls, Gelman, Himmelfarb and Jacob Burns Law libraries, Building JJ and the University Student Center. He didn’t specify when GW approved the solar panels’ installations.

Lasky said officials are also “evaluating the feasibility” of a ground-mounted solar panel system on the Virginia Science and Technology Campus.

Officials installed solar panels in May 2020 on five other campus buildings. The solar panels have an energy capacity of 497 kWAC. Officials in October 2021 said GW stopped 450 metric tons of carbon dioxide from entering the atmosphere since they began installations in 2020, equivalent to annual emissions from 90 passenger cars.

The University initiated its first solar panel project, the Capital Partners Solar Project, in 2015 in collaboration with Duke Energy Renewables, a renewable energy company in North Carolina. In 2021, a University spokesperson said GW received half of its electricity from three solar panel farms in North Carolina through the project.

Officials said the Capital Partners Solar Project will relieve “conventional electricity” of about 84,900 metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent between GW, the GW Hospital and American University — taking roughly 17,900 cars off the road.

Experts in sustainability in higher education said GW has made steps toward ambitious emission-reduction goals by installing solar panels and expanding sustainability-related academic initiatives.

Andrew Campbell, the executive director of the University of California Berkley’s Energy Institute at Haas, said the implementation of solar panels is a first step toward a University-wide mindset of sustainability. He said the impact of sustainability efforts is measured by how much of a burden the main energy grid is relieved of, which boils down to how much nongreen energy GW uses.

“I tend to think that universities should be focusing on the hard problems, not just the easy ones,” Campbell said. “Solar panels, at this point, are kind of the easy solution.”

Julian Dautremont, the director of programs at the Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education, said he sometimes sees universities take on aggressive goals to push progress further than would have been possible if they aimed to achieve a lower threshold. While a modest goal might be easily obtainable, pushing toward an aggressive goal can yield more progress, he said.

“There are potential benefits of setting more ambitious goals, even if it means you have to readjust and push back the timeline,” Dautremont said. “So I always try to not discourage folks for being ambitious.”

Dautremont said beyond pledging to meet an ambitious goal, universities should expand their initiatives to student organizations, majors, minors and other spheres of going green like composting or minimizing the use of single-use plastics. The University adopted a policy in 2021 prohibiting the purchase of single-use plastics in dining venues, except for when there are no alternatives.

GW also offers a Bachelor of Science in environmental and sustainability science and a minor in sustainability.