In 1984, researchers in Texas found the skull of an ancient amphibian species, but the specimen remained unstudied for decades as it sat in Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History storage. Four decades later, a GW doctoral student determined the skull belonged to an undiscovered species and gave it a familiar name: Kermitops gratus.

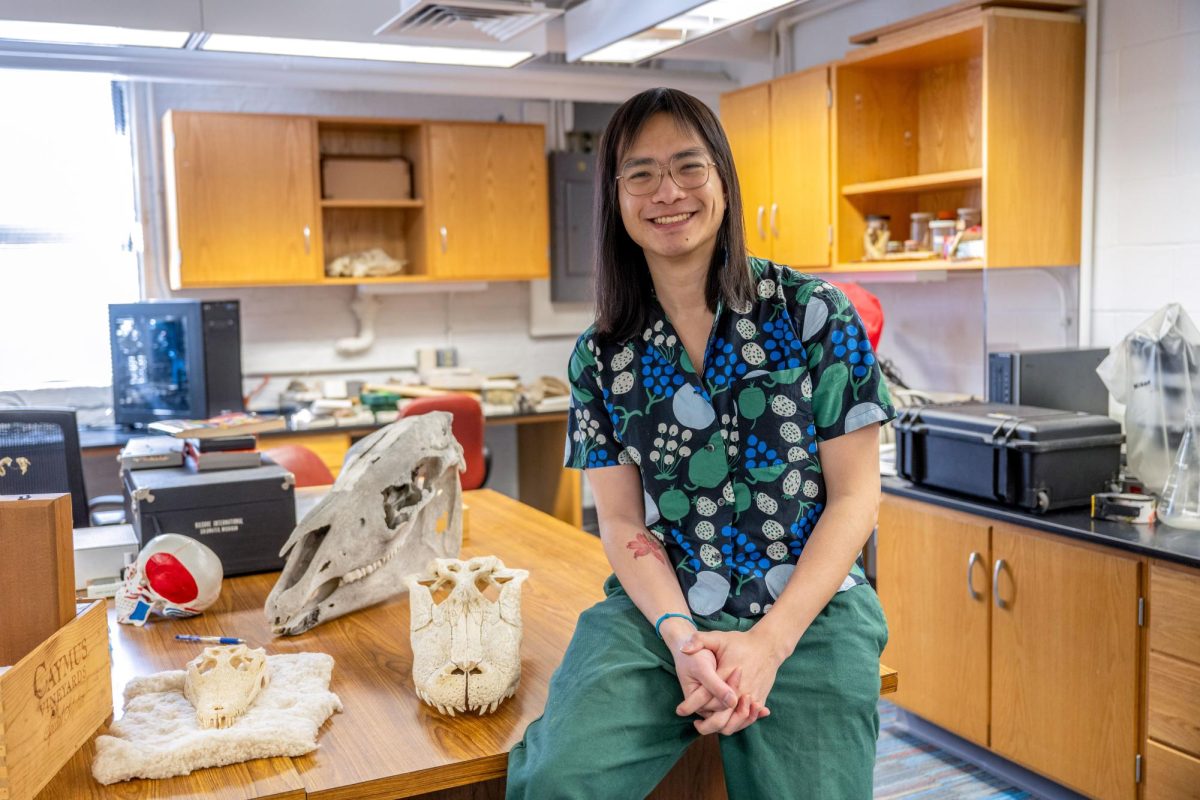

The 270 million-year-old skull — a new genus of amphibian, a broader classification category that includes related species — earned its name for its resemblance to the beloved Muppet Kermit the Frog. Cal So, the study’s lead author and a GW doctoral student, said the skull’s features set it apart from other ancient amphibian ancestors, which led researchers to determine it belongs to a new genus and expanded experts’ knowledge of the ways that modern amphibians like frogs and salamanders could have evolved.

“This bone kind of shakes up our understanding of the evolution of modern amphibians,” So said.

So, a biological sciences student, said the skull has several characteristics that have not been seen in amphibamiformes, a group of ancient animals with bone structures similar to modern amphibians. He said the most notable new characteristic of the bone is the ridge on the back of its skull.

So said Kermitops’ skull has a complex, roof structure, unlike modern amphibians with a smaller, more scaffolding-like enclosure around their brains. He said the skull’s complex structure was a surprise because existing evolutionary models projected the skull to be far simpler since the models only used data from previously known genera.

“What we essentially find is that in this group, where we expect to find things to be simplified, we see that there is actually more complexity,” So said. “It literally is more complex because Kermitops has more bones in its skull than the rest of its group.”

Determining a new species in paleontology is a challenge since researchers cannot study live specimens and rarely have complete skeletons, meaning experts often have to use subtle differences in bone structure to discern differences between species.

So said the researchers decided to name the genus “Kermitops” because its wide eyes resemble Kermit the Frog. He said the group also hopes the name will pique people’s interest in amphibian paleontology.

“The reason we named it after Kermit the Frog was because we kind of thought it did look like Kermit the Frog, especially if you’d look at some of the images that we featured in our article,” So said. “But we also wanted to draw attention to the ways that scientists can be observing and interpreting things in natural history and science in a similar way as artists.”

So said more work needs to be done to find and analyze more specimens in this genus to create a more precise evolutionary model.

“That’s part of my expectation,” So said. “If not somebody else, you know, disproving me, I’ll probably go on to disprove myself as I identify, try and dig up more information about and discover more about amphibian evolution.”

Experts in paleontology said the study has added valuable data to the field for determining the evolution of modern-day amphibians.

Jason Anderson, a professor of biology and veterinary anatomy at the University of Calgary, said the study reshaped evolutionary tree models by showing that amphibamiformes were more diverse than researchers previously thought, which helps researchers understand the origins of present-day amphibians.

“We have the new anatomy of Kermitops, and we have the new tree that their analysis entails,” Anderson said. “So it now has a new cluster of organisms that lead towards, say, the origin of modern amphibians, if that’s what it is that you’re interested in.”

Ben Kligman, a post-doctoral fellow at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, said that compared to other amphibamiformes, the Kermitops’ lengthened snout and shortened rear skull bones make it different enough from its closest relatives to consider it a new species and genus.

“There’s a whole bunch of different details of its anatomy that are unique and definitely warrant naming it as a new genus and species,” Kligman said.

Kligman said the study showed that researchers can find meaningful data from fossils that have already been collected and are in storage. He said the discovery is promising since researchers can use specimens currently in storage to make new advancements like this.

“Another cool aspect of this is that the authors found this little skull, which is about the size of your thumb, in a drawer. And it had been collected decades ago and just kind of overlooked and forgotten about,” Kligman said. “So this just tells us about how much diversity is sitting in museums in cabinets that no one’s opened in decades.”