A team of biomedical engineering students has partnered with a humanitarian organization to produce dozens of 3D-printed prosthetic limbs for children at an affordable cost.

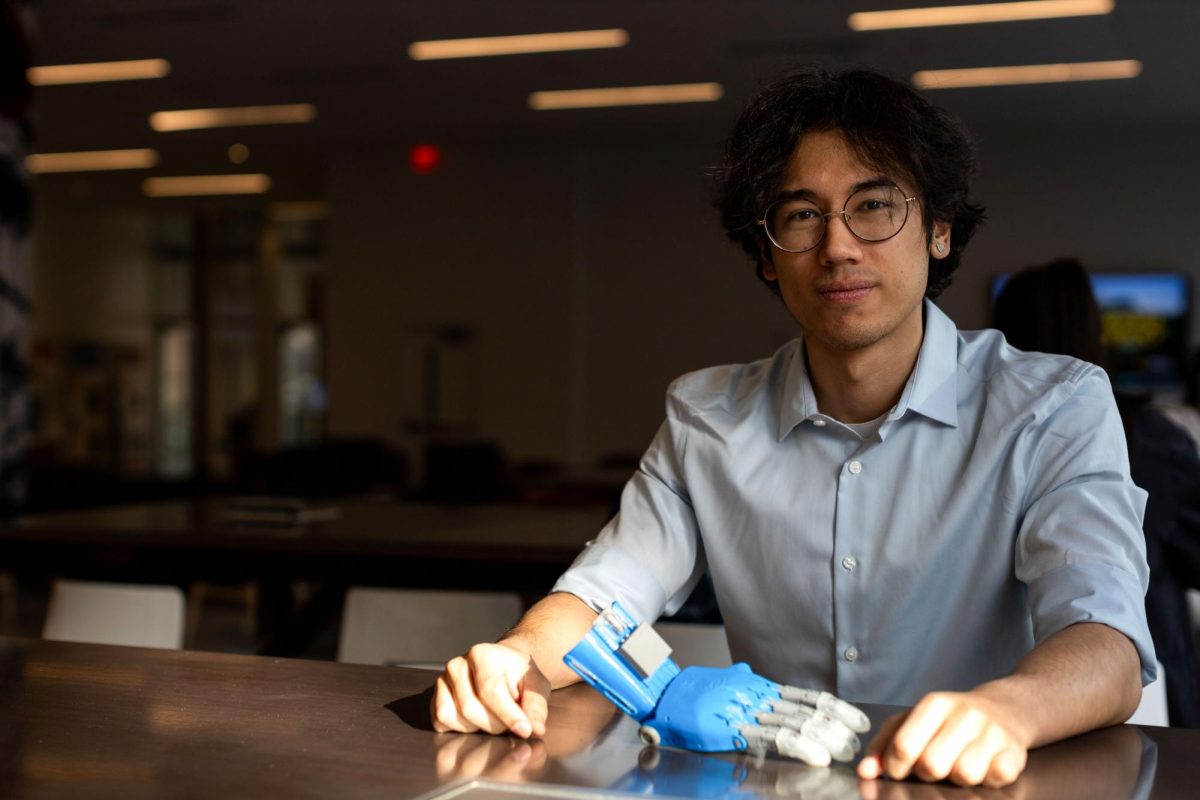

Senior Alec Tripi, a member of the GW Biomedical Engineering Society, has led a partnership since last year with e-NABLE — a national organization known for creating the first 3D printable prosthetic hand and sharing open-source designs for assistive devices — which connects amputees with prosthetics free of cost. Tripi said his team has donated dozens of these medical devices over the past few months to organizations like Infinite Technologies Orthotics and Prosthetics, which works with child amputees who frequently outgrow their devices.

“Children are not often covered by insurance for prosthetics, because they’re constantly changing in size,” Tripi said. “It’s hard to justify giving a child specifically upper-limb prosthetics because they’re constantly growing out of them, kind of like how kids grow out of shoes.”

Tripi said the partnership began with a prosthetic workshop last spring — one of a handful of philanthropic projects run by GW BMES, an engineering group focused on professional development and community outreach. He said through the workshop, members of GW BMES produced devices to donate that cost roughly $20 to manufacture, accounting for parts like printing filament and screws.

“These are very rarely covered by insurance because they’re not deemed medically necessary in a lot of cases,” Tripi said. “Additionally, they require a lot of maintenance. If they break down, you have to pay the copay fees, the repair fee, everything.”

Tripi said e-NABLE is dedicated to making affordable 3D prosthetic printing processes as widely available as possible by acting as a medium for creators to share 3D prosthetic design files. Tripi said he downloaded premade 3D models online, modified them using design software like Fusion 360 and printed them using GW’s facilities to reduce production costs.

“I’ve made my own modifications throughout the years to make it more simple, like changing where the holes are for better leverage, the tensioning, and that sort of thing,” Tripi said. “Very small modifications have been made, but the base files of these exist on the internet, they’re very easy for anybody to download, rather than having to design a hand completely from scratch.”

Tripi said he sees potential for future growth beyond the workshop last spring, and that as a researcher, he’s worked with sensors for prosthetics. He said he hopes to find a cheap way to integrate tactile feedback into his designs so that people using prosthetics can sense feeling in addition to being able to grab.

The workshop has already donated “a couple dozen” 3D-printed prosthetic limbs to local organizations like Infinite Technologies, an Arlington orthotics and prosthetics clinic, since the beginning of the partnership last spring, he said.

“I definitely hope to see this project pursued further at GW,” Tripi said. “I will actually be here next year for my master’s, so hopefully I can help whatever organizations are here and interested in furthering this project.”

Tripi said he is passionate about the seeing positive impact reducing the cost of prosthetic limbs can have on patients in becoming more mobile and active. He said the devices keep patients healthy, fit and happy, and that lower costs make the prosthetics more accessible.

“It also reduces the burden on the health care system by people being able to go out and engage and do all these things, but then also the mental health aspect of feeling normal and being able to actively participate in things is huge,” Tripi said.

BMES Co-President Zaynah Khan has recently been working with another co-president on the early stages of a project that aims to reduce patient costs for hearing aids, she said. Khan said they plan to use the 3D printer to produce the hearing aids and to donate the devices.

“It’s kind of the same idea as the prosthetics — it’s helping to design low-cost hearing aids,” Khan said.

Innovation Center Lab Technician Phoenix Price said he helped Tripi produce prosthetics for BMES last spring. Print jobs on this scale require students to cover filament costs, about $20 in Tripi’s case, but the Innovation Center in the basement of Tompkins Hall could help Tripi print the devices, Price said.

“He came about two months early and we scheduled a time and made plans for how to print the items, we printed a couple prototypes for [Tripi] using our own filament just to make sure we got the sizing right, and the costs and filament usage estimated properly,” Price said. “Then he gave us a deadline, and we made sure the printer just got his pieces out in time.”

Price said the Innovation Center is a useful resource for students working on a wide variety of projects because of its many tools and materials like 3D printers for students to use.

“Come check out the space. We do more than printing. We have textiles and electronics and sewing and knitting and crafts — everything under the sun. So if people don’t want to work on personal projects in their dorms, it’s a great space to do it,” Price said.