The University is the top private landowner in the District, but it has not ranked in the District’s top 10 property taxpayers in the past two years.

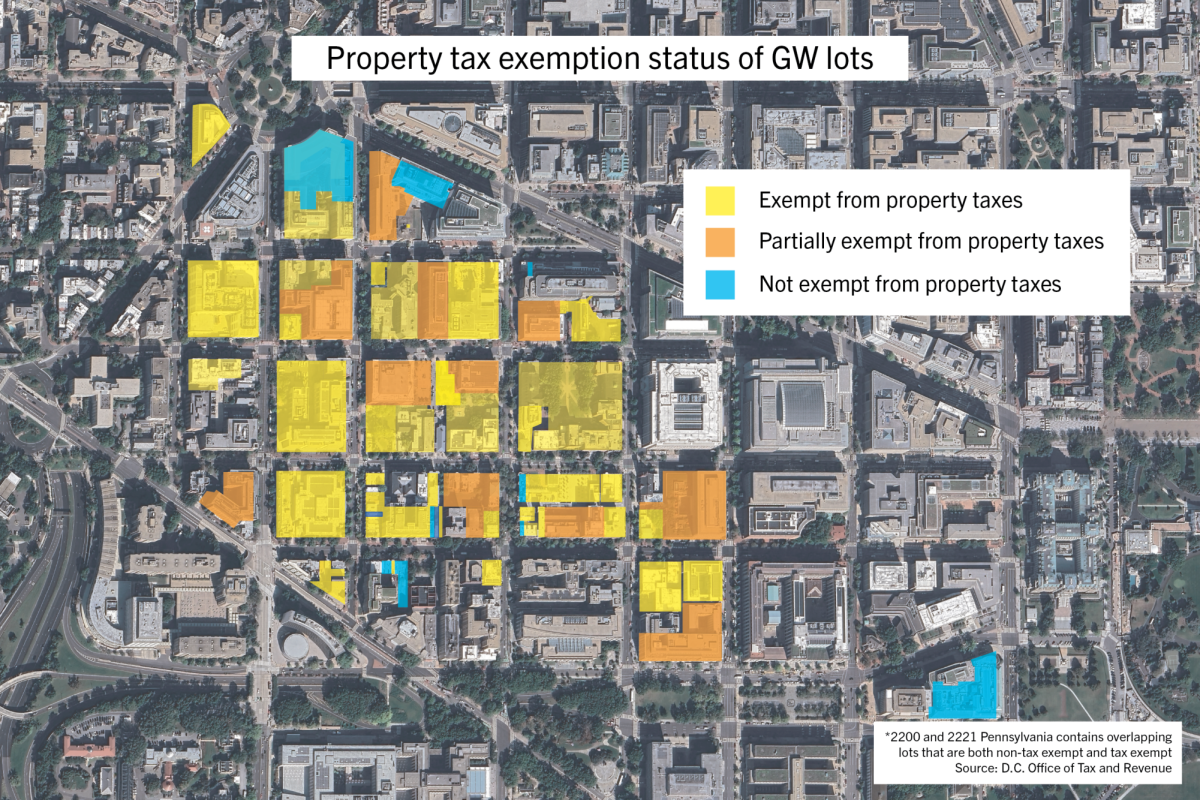

GW has a total real estate portfolio of more than $4.4 billion, including its educational and commercial buildings, according to data from the D.C. Office of Tax and Revenue. As a nonprofit, most of GW’s properties fall under an educational tax exemption, including its residence halls, gym and parking lots, exempting the University from paying more than $27 million in property taxes across 82 of its property lots in 2023, according to records from the D.C. Office of Tax and Revenue.

About 30 percent of GW’s assessed real estate value consists of fully taxed properties that include office buildings, commercial retail spaces and residential spaces. In 2022, GW made over $40 million in rental property income.

In 2023, the assessed value of GW’s fully tax-exempt properties was more than $1.7 billion, according to records from the Office of Tax and Revenue.

Tax policy experts said nonprofits like GW receive tax abatements for the educational and research value they provide, but large-scale expansion can harm the communities immediately surrounding campuses.

Adam H. Langley, the associate director of tax policy at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, said the general rationale behind universities’ tax abatements is that higher education provides massive benefits for society, like improving productivity and facilitating research.

Langley said universities and other tax-exempt nonprofits should make payments in lieu of taxes, or PILOTs, to give back to the area they work in. He said some local governments have formed agreements with schools where they pay a fraction of what they would usually pay in property taxes to offset some of the costs of hosting higher education institutions. GW has not yet instituted a PILOT program.

“The benefits are probably dispersed but the costs in terms of foregone revenue is borne fully by city residents,” Langley said. “So that geographic mismatch is one important reason for why nonprofits should be making PILOTs, including universities.”

GW has been situated in Foggy Bottom since 1912, previously having been located between 14th and 15th streets NW above Florida Avenue. Former University President Cloyd Heck Marvin added nine structures to campus over his tenure between 1927 and 1959, and former University President Lloyd Elliott expanded campus between 1965 and 1988, but University President Stephen Trachtenberg significantly bolstered campus real estate between 1988 and 2007.

Between 1985 and 2002, GW acquired more than 35 Foggy Bottom buildings, including apartment buildings and private clubs. Residents opposed GW’s expansion into the neighborhood. Michael Thomas, the then-president of the Foggy Bottom Association, argued in a 2001 op-ed that the District’s elected officials should protect nonstudent residents “at all costs.”

LaDale Winling, a history professor at Virginia Tech University, said in the second half of the 20th century, the GI Bill incentivized higher education institutions across the U.S. to expand rapidly. Winling said residents living in the areas immediately surrounding university campuses were typically the lone dissenting voices.

“The cost of that expansion happens block-by-block and neighborhood-by-neighborhood around universities,” Winling said. “And so certainly this is what neighbors in Foggy Bottom have been complaining about for decades.”

Winling said perceptions that cities were in crisis, coping with high crime and poverty led to universities attempting to take control of their surroundings by expanding their footprint between the 1950s and ‘80s. Universities extended their purview past their campus borders, taking their surroundings into their own hands.

“Essentially, they were going to have to take over the surrounding neighborhoods,” Winling said.

GW leases the ground at 2100 Pennsylvania Ave. to Boston Properties and its property at 2000 Pennsylvania Ave. to Westbrook Partners and MRP Realty.

Davarian L. Baldwin, the founding director of the Smart Cities Research Lab at Trinity College, said universities can harm the affordability of nearby housing. He said in addition to paying PILOTs, institutions of higher education should engage with and benefit the communities in which they dwell.

Today, Foggy Bottom is one of the most expensive places to rent in D.C. GW’s presence and the neighborhood’s desirable location have made it unaffordable for many long-term residents.

“Universities can provide housing. So what would it mean if we say for every university development, you expand on 20 percent of that land has to be reserved for affordable housing for the long-term residents?” Baldwin said. “What would it mean if we say that if you are going to be the biggest employer in your community for low-wage workers, that you have to provide a living wage?”

Baldwin said the factors that measure a university’s prestige, like low acceptance rates and luxury buildings, often contribute directly to them being more expensive and less accessible to low-income and long-term residents.

“How are you really serving the public good if, No. 1, you have a high rejection rate, No. 2, you have extremely high tuition and No. 3, you have unaffordable housing?” Baldwin said.