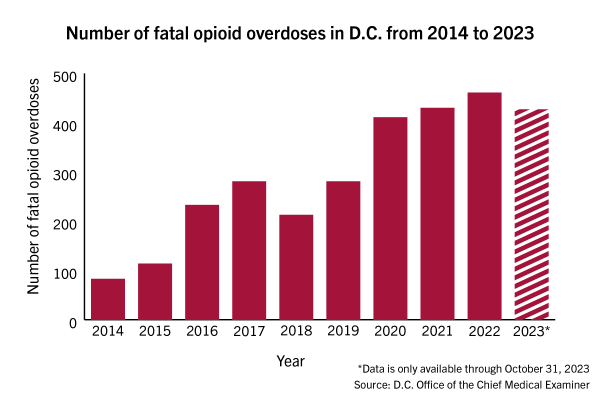

Opioid overdose deaths in the District increased last year, according to data released last week.

The D.C. Office of the Chief Medical Examiner recorded 427 overdose deaths in the District in the first 10 months of 2023, which experts in addiction and behavioral health said suggests the year’s total will likely surpass the previous year’s record high of 461 fatal overdoses. Experts said the increased prevalence of fentanyl in D.C.’s drug supply and a lack of addiction treatment resources have driven the rising opioid-related deaths in the District.

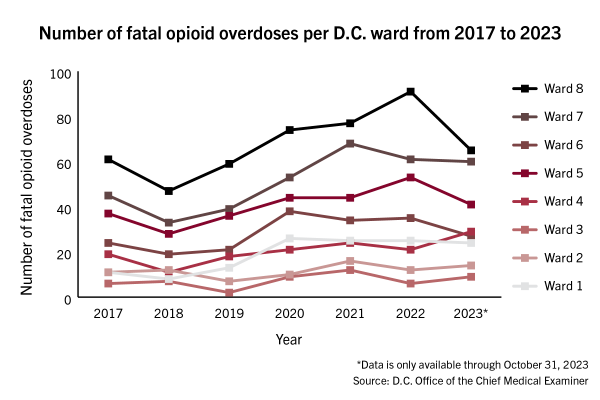

The data shows that in the first 10 months of 2023, there were 14 overdose deaths in Ward 2, which encompasses GW’s Foggy Bottom Campus, while Wards 7 and 8 sustained 60 and 65 overdose deaths in 2023, respectively. Black individuals made up 85 percent of overdose deaths, in line with the previous six years, despite the group accounting for only 45 percent of the District’s total population, according to the report.

D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser declared a public health emergency over the opioid crisis in November in response to public pressure following the steady growth in overdose deaths.

Mark LeVota, the executive director of the D.C. Behavioral Health Association, said the increase in fentanyl in D.C. directly correlates with the rising number of overdose deaths in D.C., with 98 percent of opioid overdose deaths in the District in 2023 involving fentanyl compared to 62 percent in 2016, according to the data. He said D.C. has one of the highest overdose death rates in the country because of the high levels of fentanyl circulating in D.C.’s street drug supply.

He said D.C.’s historic heroin use, an epidemic dating back to the 1960s, might have made the District an “attractive” target for drug dealers because D.C.’s opioid epidemic has primarily related to street drugs, unlike other parts of the country where the opioid crisis is linked to prescription drugs.

“That continuous street drug market for opioid drugs has also contributed to the District being one of the jurisdictions that has the highest penetration of fentanyl,” LeVota said.

He said older Black men residing in Wards 7 and 8 historically represented the largest population of heroin users in D.C. and the District historically did not provide access to treatment resources to this population. He said older Black men in Wards 7 and 8 are still impacted by structural racism surrounding the allocation of resources in D.C and continue to be disproportionately likely to overdose as opioids become more deadly.

The District’s first stabilization center — providing emergency crisis intervention, counseling and resources to sustain long-term recovery for individuals experiencing substance-use disorder — opened in October in Northeast D.C. LeVota said the center is primarily staffed by people with “lived experience” in opioid use. He said the stabilization center has provided services to roughly 400 individuals since its opening.

“It’s a good additional resource for our first responders so that they can take people where they can stabilize, where they’re willing to go, even if they may not be willing to go sit in a hospital emergency department,” LeVota said.

In April, D.C. officials rolled out six harm-reduction vending machines stocked with Naloxone, or Narcan — a medication that rapidly reverses an opioid overdose — and fentanyl test strips in areas with higher average drug overdoses, like Wards 6, 7 and 8. LeVota said people have taken about 4,000 items from the vending machines since their implementation.

Wilson Compton, the deputy director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse and an addiction psychiatrist, said Naloxone distribution is a life-saving strategy and that vending machines can increase access. He said individuals need to have Narcan on hand before an overdose occurs because if someone stops breathing, there are only a few minutes to resuscitate them.

“What is a little unnerving though, is you need to have it beforehand, because there often isn’t time to go run to the vending machine, figure out how to use it, obtain the product, and then administer it,” Compton said. “That may take too long.”

He said fentanyl’s unpredictability makes it lethal because similarly sized packages of fentanyl can have different potencies depending on if the drug was diluted with other agents. He said drug dealers are also contaminating other drugs with fentanyl without disclosing it, meaning people using methamphetamine or cocaine might be unaware they are ingesting fentanyl.

Josh Lynch — the chief medical officer and founder of MATTERS, a site based in New York that facilitates referrals for outpatient treatment for opioid use disorder — said COVID isolation caused an uptick in opioid-related deaths because pandemic shutdowns obstructed people’s ability to connect to treatment.

“Besides that, the other major factor in causing increased overdose deaths is that the opioid supply — which for the last part is fentanyl, it’s really not heroin as much anymore — but a lot of fentanyl has been contaminated with something called xylazine,” Lynch said.

Xylazine, also known as Tranq, is a veterinary sedative, and since it is not an opioid, Narcan does not reverse its effects, Lynch said. The District has recorded an increase in xylazine-related deaths, rising from three in 2020 to a dozen in 2023, according to the data. In 2021, the Drug Enforcement Administration reported a widespread threat of fentanyl mixed with xylazine, and the agency seized drugs containing the mixture in 48 states.

Lynch said the people most vulnerable to overdose are those who went through a period of nonuse, like jail time or in-patient rehabilitation, because once they have access to opioids again, they consume the same amount of drugs as they did before but with lower tolerances.

“Getting solid linkage to treatment is super important, especially in those transitions,” Lynch said.

Nancy Nielsen, a senior associate dean for health policy at the University of Buffalo’s Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, said public health experts need to partner with first responders and law enforcement to get people into treatment in a nonpunitive way. She said drug courts, courts specifically for cases involving addicted defendants facing nonviolent misdemeanor or felony charges, offer an approach to helping addicts receive treatment and prevent more criminal activity.

For a first-time offender, possession of a controlled substance in D.C. results in a misdemeanor, up to 180 days incarcerated and a $1,000 fine, according to D.C. law.

“That’s really important because that gives people who are going to be jailed the opportunity to try to get clean with the help of medication and it avoids stigmatizing them as a hardened criminal and acknowledges that they did a criminal thing and they may have to pay for that,” Nielsen said.