The Title IX Office reported a 6 percent increase in the number of new complaints of sexual harassment, sexual assault, domestic and dating violence, and stalking filed at GW in the 2022-23 academic year, according to the office’s second annual report released last month.

The report states that the Title IX Office received 405 new reports of sexual harassment, sexual assault, stalking, dating violence, domestic violence and retaliation in the Title IX process between July 1, 2022, and June 30, 2023, compared to 380 the previous year. Asha Reynolds, the Title IX Office’s director and coordinator, said the increase in reports does not necessarily reflect an increase in incidents but could indicate more awareness of campus resources and engagement with the Title IX Office’s supportive measures, like academic accommodations or a mutual no-contact order between two individuals.

The Title IX Office’s annual reports expand on GW’s Annual Security and Fire Safety Report, which discloses the locations of crimes, semester breakdowns and who reports an incident. The Title IX report’s data on sexual assault, domestic and dating violence and stalking differs from the annual security report’s data, which has separate incident reporting criteria for the GW Police Department under federal law.

“This report highlights the need to continue to expand upon sexual harassment prevention and education efforts,” Reynolds said in an email.

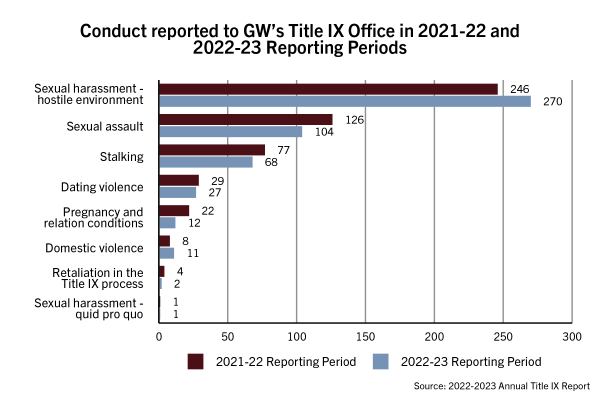

Of the 405 reports filed last academic year, 270 were cases of sexual harassment, 104 were sexual assault, 68 were stalking and 27 were dating violence. Eleven were domestic violence, two were retaliation in the Title IX process and 12 were requesting support for pregnancy and related conditions, according to the report.

In the 2021-22 academic year, 246 of the 380 reports filed were cases of sexual harassment, 126 were sexual assault and 77 were stalking, according to the office’s first-ever Title IX report last year. The office also received 29 reports of dating violence and 22 for pregnancy and parental services that year, per the 2021-22 report.

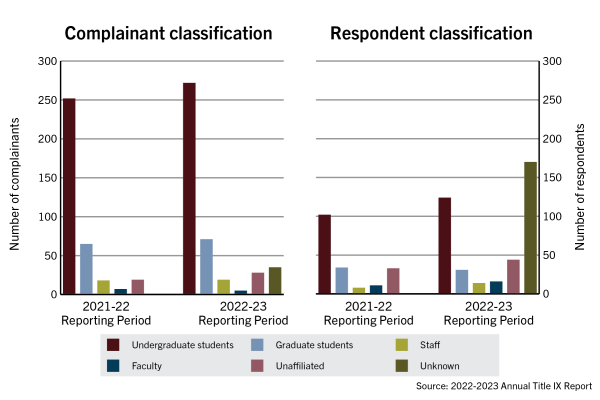

Reynolds said last year the Title IX Office tracked when there was an “unknown party” associated with the report, meaning the reporter did not provide the Title IX Office with a first and last name for either the complainant or the respondent. This year the report separated “unknown party” into “unknown complainant” and “unknown respondent,” she said.

Unknown respondents — individuals reported to be the perpetrator — represented the highest number of reported respondents with 170 reports, followed by 124 undergraduate students, 44 unaffiliated respondents, 31 graduate students, 16 faculty and 14 staff respondents, according to the report.

Reynolds said without the respondent’s identity, the Title IX Office can’t engage in the resolution process that determines whether there was a Title IX policy violation, but complainants can still access supportive measures.

“The high number of unknown respondents is directly related to how the Title IX Office strives to respect complainant autonomy throughout their engagement with the office,” Reynolds said. “One of the most common ways that is achieved is by not requiring a complainant to share the identity of a respondent unless they would like to.”

The report states that 272 complainants were undergraduate students, 71 were graduate students, 35 were unknown, 28 were non-GW affiliates, 19 were staff and five were faculty.

Like the previous year, the majority of reports were filed by designated reporters — GW community members like faculty and staff who are required to report suspected or alleged sexual harassment to a Title IX Coordinator — who filed 253 reports, an increase from 217 the previous year. Complainants filed 110 reports on their own behalf, 26 students made reports on behalf of someone else, non-GW affiliates made six reports, those reported to be perpetrators made two and eight cases were reported anonymously, per the report.

The report states that similar to last year, the majority of complainants chose not to initiate a formal resolution — when the Title IX Office determines a policy violation occurred and considers subsequent disciplinary action — or an alternative resolution, when both parties and the University agree on a resolution. Almost 150 complainants chose to obtain supportive measures, 122 chose not to respond to the Title IX Office’s outreach email following the filing of their report and 84 chose not to request further action.

The report states that the Title IX office worked on four formal resolutions and five alternative resolutions to formal complaints, compared to seven formal resolutions and 12 alternative resolutions the previous year.

The Title IX Office, in conjunction with the Office of Advocacy and Support, also launched in June the Sexual Assault and Intimate Violence Helpline, a confidential resource for community members who have experienced sexual assault, sexual harassment, stalking, and dating and domestic violence, per the report. Reynolds said clinically trained professionals who can provide crisis counseling, safety planning and emotional support staff the helpline.

“In the immediate aftermath of an incident, it is important that community members have a resource that they can speak to confidentially regarding their option to report and what reporting might entail so that they can make an informed decision about whether reporting is right for them,” Reynolds said.

Title IX experts said annual reports can inform campus community members about the Title IX Office’s resources and procedures and that increases in reports likely signify more awareness of resources.

Kristi Clemens, the assistant vice president for equity and compliance and the Title IX coordinator at Dartmouth College, said Title IX reports can show campus community members that complainants decide the actions that come after they file a report, like whether they seek supportive measures or pursue a formal or informal process. She said providing public Title IX data can change the perception that Title IX offices don’t take reports seriously.

She said many factors could contribute to increases in reports, but higher numbers of reports generally correlate with increased awareness of Title IX Office resources and trust in Title IX processes, instead of the increased prevalence of Title IX violations.

“I do think that it correlates to an increase in awareness of resources and trust in the process,” Clemens said. “Trust that if I make this report, I’m going to be taken seriously. I’m going to receive support and resources and I’m going to have options for resolution.”

Christian Basi, a spokesperson for the University of Missouri, said not every student reads their university’s Title IX report but that it’s beneficial for students to have the data to so that they can utilize the report to find Title IX resources.

He said the University of Missouri’s Office of Institutional Equity, which encompasses Title IX, uses their report’s data to watch for trends like repeated reports about a particular person or a particular action to decide to launch campaigns to inform students with tips to mitigate chances of being a victim, instead of increases in total reports.

“Nowadays when we see increases it’s really difficult to pinpoint to a particular reason for an increase,” Basi said. “What our Office of Institutional Equity watches for is, as they have cases coming in or reports coming in, they watch for trends in those individual reports.”