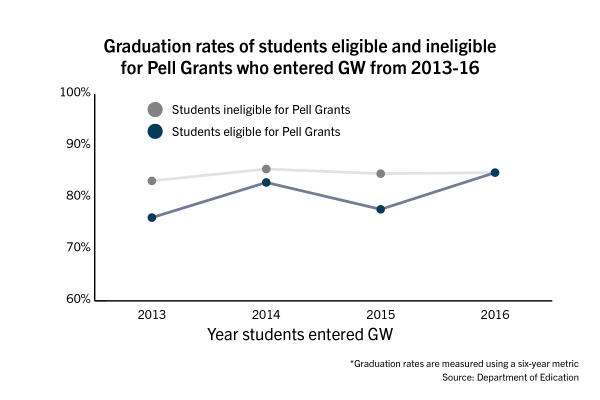

Students who entered GW in 2016 and received Pell Grants graduated at the same rate as those who did not, according to new institutional data.

Students who entered the University in 2016 had a six-year graduation rate of 84.8 percent, closing the gap in graduation rates between students eligible and ineligible for the Pell Grant, according to the Department of Education. DOE data shows the lack of a gap between Pell-eligible and non-Pell-eligible students is an improvement from students who entered GW in 2013, which showed students were 7 percent more likely to graduate if they were not eligible for the grants.

Pell Grants are federal aid awards given to students with high financial need, which is calculated from their expected family contribution toward tuition and a university’s cost of attendance. The six-year graduation date is a common measurement point for academic metrics since it’s the average time taken to earn a bachelor’s degree.

The graduation rate gap between Pell-eligible and non-Pell-eligible students at GW shrunk to 2.6 percent for students who entered in 2014 — when 85.5 percent of non-Pell students graduated, compared to Pell students’ 82.9 percent graduation rate — and swelled to 6.9 percent for 2015’s entrants.

University spokesperson Julia Metjian said GW supports Pell students through programs like a new summer recovery academy for students who were not meeting their “academic progress goals” and “success coaches” for students who are struggling academically.

The Office of Student Success’ Summer Academy is an invite-only program for students on academic probation or behind on earning credits toward graduation and offers to cover housing costs for some students based on financial need. Students, faculty and staff can refer a student to the CARE Team, a group within the Division for Student Affairs that provides resources for students to stay and succeed at the University.

“Financial support has been provided to help students coming from families with lower adjusted gross income levels,” Metjian said. “Additionally, active use of the early alert and CARES notification system has allowed for expedited engagement with students experiencing varying stress levels both in and outside of the classroom.”

Then-University spokesperson Tim Pierce said in 2022 that roughly 14 percent of first-year students have qualified for Pell Grants since 2017.

Experts in college access and affordability said it is “easier” for selective schools like GW to close the gap between Pell-eligible and non-Pell-eligible students’ graduation rates because their student bodies tend to have fewer educational barriers to overcome.

Jeremy Wright-Kim, an assistant professor of education at the University of Michigan, said Pell-eligible students at most universities graduate at a lower rate than non-Pell-eligible students because many Pell-eligible students have to work to financially support themselves during college, limiting time for their studies. He said many Pell recipients are also first-generation college students who have to navigate higher education without support from parents who have experienced it firsthand.

He added that universities should provide cultural programming because many Pell students are racial minorities, which would allow them to ease into a culturally supportive college environment.

“We know that if you feel engaged at your institution, if you’re supported, if you feel like you belong, you’re more likely to persist,” Wright-Kim said.

Wright-Kim said many Pell-eligible students attend less-selective universities because of inequity that starts in their youth. He said some Pell-eligible students’ high schools are less likely to offer Advanced Placement courses and extracurricular activities that would boost their college applications, leading more students to end up at less-selective universities with lower graduation rates.

He added that universities’ consideration of their applicants’ financial need during admissions may also decrease the number of Pell-eligible students they accept because they may not be able to afford matriculating into the University. Officials admitted in 2013 to placing hundreds of applicants on the waitlist because they could not afford GW’s tuition.

“A lot of the onus, I believe, should also be on these institutions to address their cost issues, to address their information disconnect and for their own admissions processes,” Wright-Kim said.

Sandy Baum, a senior fellow in the Center on Education Data and Policy at the Urban Institute, said selective institutions like GW tend to have higher Pell student graduation rates than less selective universities because they recruit “promising” students, regardless of their family’s income. She added that universities may give more consideration to applicants’ socioeconomic statuses during admissions to recruit a diverse student body after the Supreme Court barred the consideration of race in college admissions in June.

Baum said university resources, like writing centers and preparatory courses for admitted students before entering their first year, can boost Pell recipients’ performance in the classroom. She said universities can provide an emergency aid system that grants financial assistance for unexpected events like stolen laptops or medical procedures.

The GW Cares Assistance Fund provides short-term financial aid of up to $1,000 for full-time and part-time undergraduate and graduate students. The School of Media and Public Affairs offers the Cokie and Steve Roberts SMPA Student Support Fund, an emergency fund that grants financial assistance of up to $7,500 to undergraduate SMPA students on a rolling basis.

“There are things other than ability and motivation that influence how well students adjust to a college environment,” Baum said. “And lack of familiarity with that environment is a real barrier. It’s not the student’s fault.”

Zoë Corwin, a research professor of higher education at the University of Southern California, said universities can ensure Pell students graduate college by offering financial assistance for “hidden” costs associated with higher education like transportation and family visits. She said universities can also offer housing stipends for students to live on campus during the summer and work an unpaid internship, which would help increase Pell students’ career success after graduation.

The Center for Career Services offers the Knowledge in Action Career Internship Fund, which grants $750 to $3,000 to undergraduate and graduate students working unpaid internships. The SMPA Career Access Network Internship Fund grants $1,000 to $3,000 for rising juniors and seniors working an unpaid or low-paid internship during the summer.

The Gilman International Scholarship Program, which provides up to $5,000 for Pell recipients to study abroad, named GW as a top producer of Gilman Scholars in December.

Corwin said the graduation rates of Pell students is reliant on the commitment of the universities to Pell student success.

“It’s one thing for a university to say, ‘We welcome a diverse group of students and recruit a diverse group of students to the university,’” Corwin said. “It’s another thing to ensure that they have the programs to support students while they’re there.”

She said GW can maintain the absence of a gap between the graduation rates of Pell-eligible and non-Pell-eligible students by allowing the accomplishment to “guide” their practices as a university.

“It needs to stay at the front of leadership practice, leadership concerns and how faculty and staff are thinking about supporting students,” Corwin said.