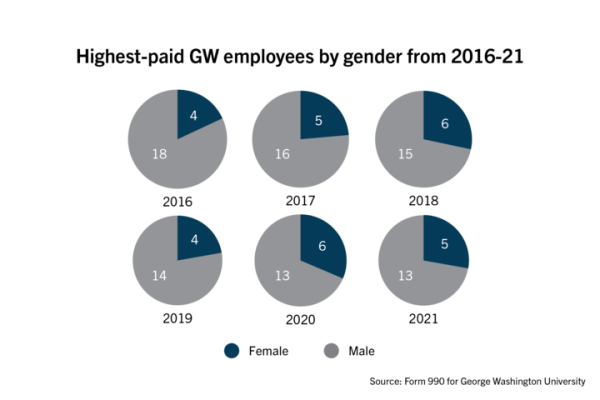

Five of GW’s 18 top-earning employees in 2021 were women, according to University tax forms.

The bump in representation is a slight increase from seven years ago, when four of the top 22 earners in 2016 were women, according to the University’s Form 990 — a tax form for nonprofit institutions that lists the organization’s officers, directors and highest compensated employees. Experts in higher education administration diversity said women are underrepresented in top university roles across the country due to a lack of pay equity and a low prioritization of hiring women.

“Institutions may have made more of an effort, but it hasn’t had as much of an impact,” said Lynn Pasquerella, the president of the American Association of Colleges and Universities. “In fact, the situation for women has gotten worse as a result of COVID-19, when many women had to serve as caregivers for children or for other family members in ways that stalled their careers.”

The number of employees reported on the form fluctuates each year because organizations are required to report current and former officers, directors, trustees and “key employees” — the five current highest-compensated employees.

The University’s gender disparity among its highest-compensated employees has remained largely consistent since 2017, when five of 21 were women. Women accounted for six of GW’s 21 top earners in 2018, four of 18 in 2019, and six of 19 in 2020.

Barbara Bass, the vice president for health affairs and the dean of the School of Medicine and Health Sciences; Beth Nolan, the senior vice president and general counsel; Dana Bradley, the vice president and chief people officer; Donna Arbide, the vice president for development and alumni relations; and Lynn Goldman, the dean of the Milken Institute School of Public Health, were the five top-earning female employees listed on the 2021 form.

The form reveals that Bass received the highest compensation of the women — receiving $1,324,917 in 2021 — with Nolan coming in second with a compensation of $825,497. All five women fall into the top-10 highest-earning employees of the 18 employees listed, according to the form.

Pasquerella said faculty and staff may not be aware of gender pay disparities, and women tend to not negotiate for higher pay.

The number of female faculty members decreased from 646 faculty members in 2019 to 604 in 2021. Faculty said female professors left the University when the pandemic put stress on their familial roles.

“It’s not that institutions are unaware of the problem,” Pasquerella said. “It gets back to the hidden barriers and biases that militate against women taking on leadership roles.”

Ann Marcus, a professor of higher education and director of the Steinhardt Institute of Higher Education Policy at New York University, said universities need to be proactive about seeking women out when positions open for hire.

Last spring, GW announced the hiring of Ellen Granberg, the University’s first female president, amid a national wave of female university president hirings.

“They have to bring the issue to the forefront of the consciousness of people who do the hiring,” Marcus said. “There’s been some progress because institutions will be more intentional about how they recruit people.”

Marcus said GW has more women in senior positions than many other universities because there are several women in vice presidential roles.

“Having that many women at such high salaries is pretty striking,” she said.

Five of GW’s 12 peer schools — University of Miami and Northeastern, Tulane, Wake Forest and Georgetown universities — have a lower percentage of women in their top-paid roles, which all list male athletics coaches as their top-paid employees, with the exception of Northeastern, whose highest-paid employee was their university president.

Five of GW’s other peer schools report a higher percentage of women in their top-paid roles, ranging in growth from 4.3 percent to 27.3 percent. Two universities, University of Pittsburgh and Syracuse University, have a matching rate of women in their highest-compensated roles, according to their schools’ Form 990s.

Mary Churchill, the program director of higher education administration at Boston University’s Wheelock School of Education and Human Development, said 24 percent of top earners at top research universities across the country are women.

“Even if you hire men and women at the same rate, men are more likely to negotiate and ask for more throughout and then this pay inequity rises even within the same position,” Churchill said.

Churchill said women often feel “uncomfortable” negotiating for higher pay and do not realize the market value of their work. She said hiring men and women at the same initial pay rate presents one way universities could alleviate the disparity.

She said if universities share their employees’ compensation with all faculty and staff, it will be easier to close the wage gap for top positions.

“I think the more you show what’s happening on campus and make that transparent, you will see more institutions being more equitable,” she said.