There are only so many puns to make about an intensely local, yearslong dispute over two “Transformers” sculptures outside of a Georgetown townhouse. So here goes nothing – there’s more than meets the eye when it comes to this quintessentially Georgetown quarrel.

The life-size statues are built out of an assortment of car parts and bear a striking resemblance to Bumblebee and Optimus Prime. If you haven’t had the pleasure of seeing these artful Autobots yet, you can find them standing guard on the sleepy sidewalk of Prospect Street. But you should hurry. The Old Georgetown Board, a federal panel with the power to approve or deny architectural and aesthetic changes in the neighborhood’s historic district – which effectively encompasses all of Georgetown – ruled earlier this month that the statues must come down because they threaten the neighborhood and its “historic character.”

The Board and neighborhood groups argue the sculptures stick out like a sore thumb in a neighborhood of federalist architecture, cobblestone streets and grand 18th-century manors. Most neighbors of Newton Howard – the Georgetown University neuroscientist who owns the disputed duo – decorate their homes with planters instead of reflecting mankind’s relationship with machines.

These sculptures don’t spoil the neighborhood’s history or its character. But they are different, and that seems to be a cardinal sin in Georgetown. When I cast my gaze across Rock Creek from Foggy Bottom, I see a deeply suburban mindset behind Georgetown’s drive for sameness. While the neighborhood is far from a master-planned community, its attitude toward anything different reminds me of where I grew up in the suburbs of Atlanta.

Community swimming pools, cookie-cutter homes and, most of all, conformity define towns like Johns Creek and Cumming, Georgia. Homeowners associations measure the height of your grass, check the color of your shutters and track when you put your trash out – at least mine do, anyway. The homes in these tightly run neighborhoods lack the centuries-old history of Georgetown’s housing stock, but the overriding focus on preserving “neighborhood character” – not to mention property values – is the same. Anything out of the ordinary, from an untrimmed shrub to a car parked in the street, incurs the wrath of angry neighbors and the Nextdoor crowd.

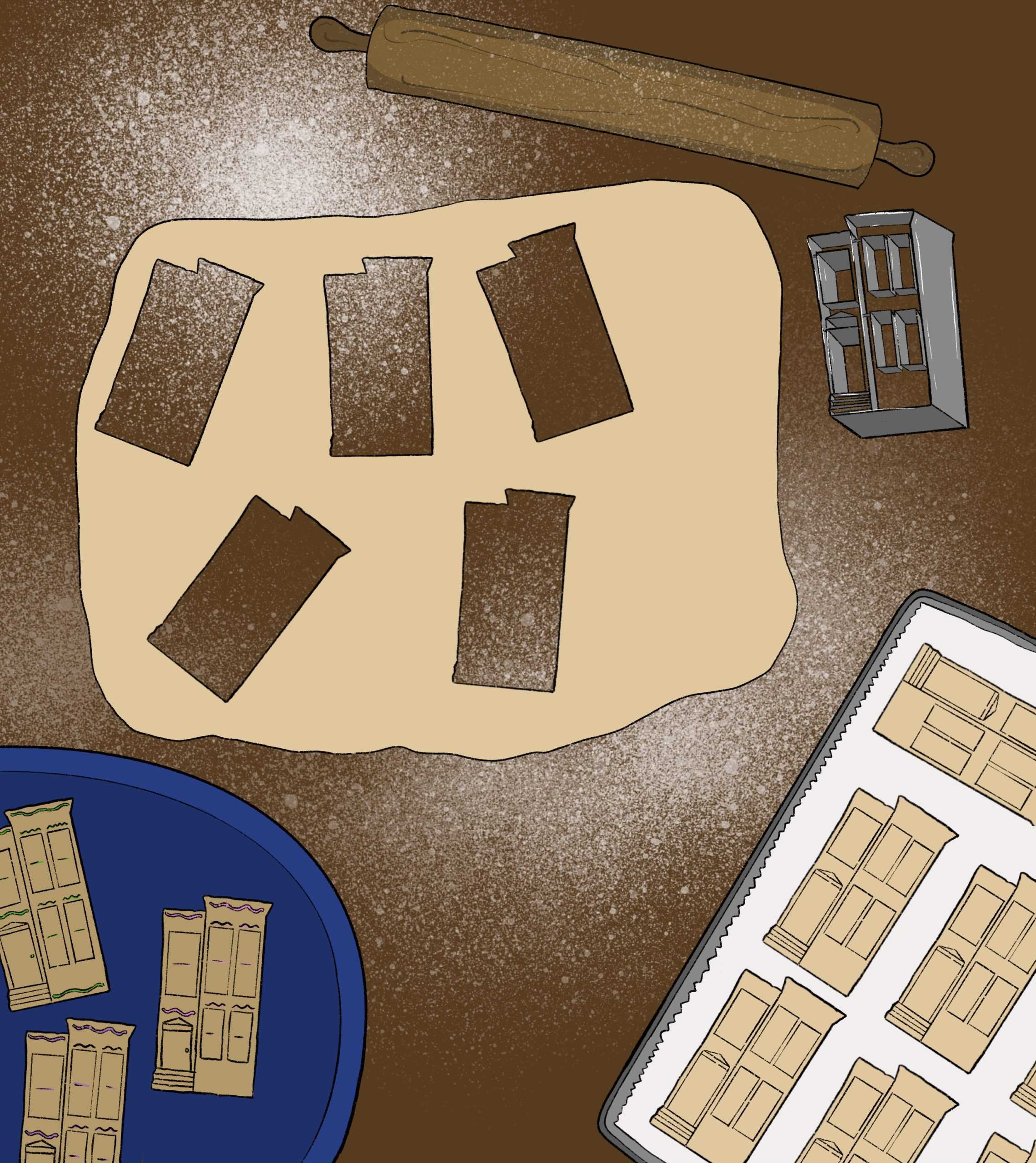

Maura Kelly-Yuoh | Staff Cartoonist

But not everyone wants to keep up with the Joneses, even if they live in a historic neighborhood or a shockingly authoritarian subdivision. From Georgia to Georgetown, people are quietly rebelling against the same old same old, the rules of HOAs and federal boards be damned. Come to my neighborhood in Georgia, and you’ll understand what I mean. Stroll past that faux skeletal triceratops that lounges on my neighbor’s lawn, chowing down on the leafy contents of a potted plant. Admire the bravery of the homeowner who dared to use a chain link fence instead of a wooden one. Stop by the house on the corner – though Christmas comes but once a year, its enormous, illuminated sign reading “JOY” is the gift that keeps on giving all season long.

But whether it’s a triceratops or a Transformer, the gaudy and the garish still aren’t world- or neighborhood-ending threats. At a certain point, they’re just part of the neighborhood.

I’ve gone to bat for historic preservation on campus after the University in 2021 demolished Waggaman House, which housed the Nashman Center for Civic Engagement and Public Service, and razed Staughton Hall in 2022. But the Old Georgetown Board’s decision isn’t an attempt to maintain historic or noteworthy architecture – that’s not what’s at stake here. Howard isn’t tearing down his historic, $4 million townhouse or starting new construction, two actions that would fall under the purview of the Old Georgetown Board.

Instead, the Board and residents are focused on preserving a nebulous vibe of “old.” You can maintain a building, but freezing a neighborhood in time is impossible – Georgetown has traffic lights and stop signs, and its well-to-do residents seem to have swapped the horse and carriage for BMWs and Range Rovers. If automobiles pass the test in tony Georgetown, then why can’t Autobots?

Juxtaposition, not homogeneity, gives neighborhoods their character. Just look at Foggy Bottom’s Historic District, where apartment buildings and hotels mingle with historic row houses. The past and the present complement each other and so do historic preservation and self-expression. Who wants to live in a museum piece? A little individuality here or there is a fair price to pay for the maintenance of D.C.’s historic architecture and urban fabric. The best neighborhoods can make room for new buildings and uses or, at the very least, people who want to be different.

Whether I stay in D.C. or move elsewhere once I graduate next year, I’ve realized I don’t only want a neighborhood with character – I want a neighborhood with characters. Georgetown may be as staid as ever, but let’s not let historic preservation quash self-expression.

Ethan Benn, a junior majoring in journalism and mass communication, is the opinions editor.