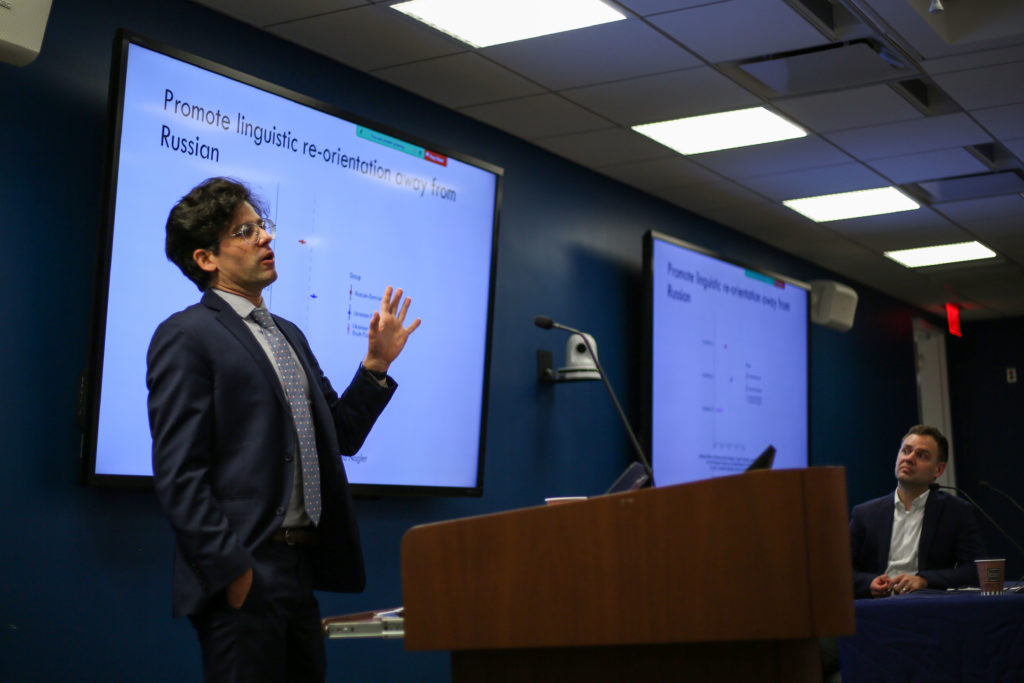

Aaron Erlich, an assistant professor in the political science department at McGill University, spoke about pro-Kremlin propaganda in the context of the invasion of Ukraine Thursday.

The event, titled “Pro-Kremlin Propaganda’s Failure in Ukraine: Evidence and Lessons Learned,” was hosted by the Institute for European, Russian and Eurasian Studies in the Elliot School of International Affairs and the Program on New Approaches to Research and Security in Eurasia, a group of academics mostly based in North America and post-Soviet Eurasia located at IERES and the Elliott School. David Szakonyi, an assistant professor of political science at GW, introduced Erlich to the audience both in person at the Elliott School and on Zoom.

Erlich discussed his research in the role propaganda plays in Ukrainian or Russian support for the Kremlin, saying Ukrainians are able to resist pro-Kremlin propaganda with higher levels of critical thinking than other societies.

“What we’ve seen is, no matter where you are on the Russian orientation spectrum, the more you engage in analytical thinking, the less likely you are to believe pro-Kremlin disinformation and the more likely you are to believe true stories,” Erlich said.

Erlich also discussed the role Russian television and language plays in support or opposition to current Russian President Vladmir Putin.

“What we find is that people who generally spoke Russian, trusted Vladimir Putin more,” Erlich said.

Erlich said Russian public opinion of the war continues to be “fairly high” in favor since Russians prefer state media over foreign media that is critical of the country. He also said the Russo-Ukrainian war has split families not just physically but ideologically as well.

“Of our sample, of the 534 people, 54 percent said there was no change, that they weren’t able to actually influence their relatives at all,” Erlich said. “But, I want you to notice that the eight percent there is a relatively small level of backlash, overall. Much smaller than the positive effect that people reported having.”

Erlich also said the empirical results would be difficult to prove since the particular study he referenced required participants to self-evaluate their circumstances.

Szakonyi and the audience then asked questions of Erlich covering topics like how age affects susceptibility to Russian propaganda.

One audience member asked Erlich about whether concerns surrounding current threats of foreign propaganda and disinformation campaigns worldwide were over-exaggerated or not talked about enough.

“To the extent that we care about actually really engaging with very specific kinds of types of disinformation, that’s going to be context and time specific,” Erlich said. “And we need to know each society’s particular vulnerabilities.”