The U.S. Supreme Court’s conservative majority’s skepticism about race-conscious admissions could upturn how GW and other universities evaluate prospective students. Students for Fair Admissions, an organization led by anti-affirmative action activist Edward Blum, alleges that Harvard University’s and the University of North Carolina’s admissions policies unfairly reject Asian and white applicants because of their race. The two cases have been working their way through the legal system since 2014, the latest in a series of legal battles stretching back to the 1970s challenging what factors higher education institutions can consider in their admissions processes.

Demanding that universities ignore the backgrounds of their applicants in the name of “race-blind” admissions misunderstands the role of diversity in higher education. “Diversity encourages students to question their own assumptions, to test received truths and to appreciate the complexity of the modern world,” the brief GW and 15 other institutions filed in support of Harvard in the affirmative action lawsuit in 2018 states. And with or without affirmative action as we know it, such diversity is worth defending.

As federal legislation in the 1960s and 1970s aimed to eliminate discrimination against minority groups in education, employment and government contracting, affirmative action programs extended these opportunities to people of color, people with disabilities, women and other minorities in the public and private sector. In the realm of higher education, affirmative action pushed public universities like UNC and private universities that receive federal funding like Harvard to actively enroll students of color after decades of discriminatory admissions.

GW, with its own sordid history of segregation, is no exception. From 1927 to 1959, then-University President Cloyd Heck Marvin ruled the University with an iron fist, suppressing academic freedom, curbing student self-governance and abetting racial intolerance, according to a 1940 Alumni Committee report. In 1938, Marvin wrote that “students of any race or color perform their best” when they are in a “homogenous group, and the University, in its tradition and social environment, has long preserved this policy.” GW officially accepted all students regardless of race in 1954 despite Marvin’s opposition. It was the last D.C. area university to desegregate its admissions process.

Desegregation and officials’ subsequent consideration of prospective students’ backgrounds as part of the admissions process has transformed GW’s student body. Granted, GW is still a predominantly white University – 47.1 percent of all students enrolled in 2021 were white. But from 2012 to 2021, the percentage of Hispanic, Black and Asian students enrolled at GW has respectively increased from 5.9 to 10.2 percent, 8.7 to 10.7 percent and 8.6 to 11.5 percent for Asian students, according to the University’s enrollment dashboard.

Living and learning alongside people whose experiences, identities and perspectives differ from each other is critical to the mission of any university. And while officials at GW and other institutions could certainly do better to clarify their “holistic” admissions process, those who cry foul over affirmative action or bemoan “reverse discrimination” should know that no U.S. college admits or denies prospective students solely because of their race. Race-conscious admissions treat an applicant’s race as one of many factors, like academic performance or extracurricular interests, rather than a decisive one. Doing so expands minority students’ access to historically segregated institutions of higher education.

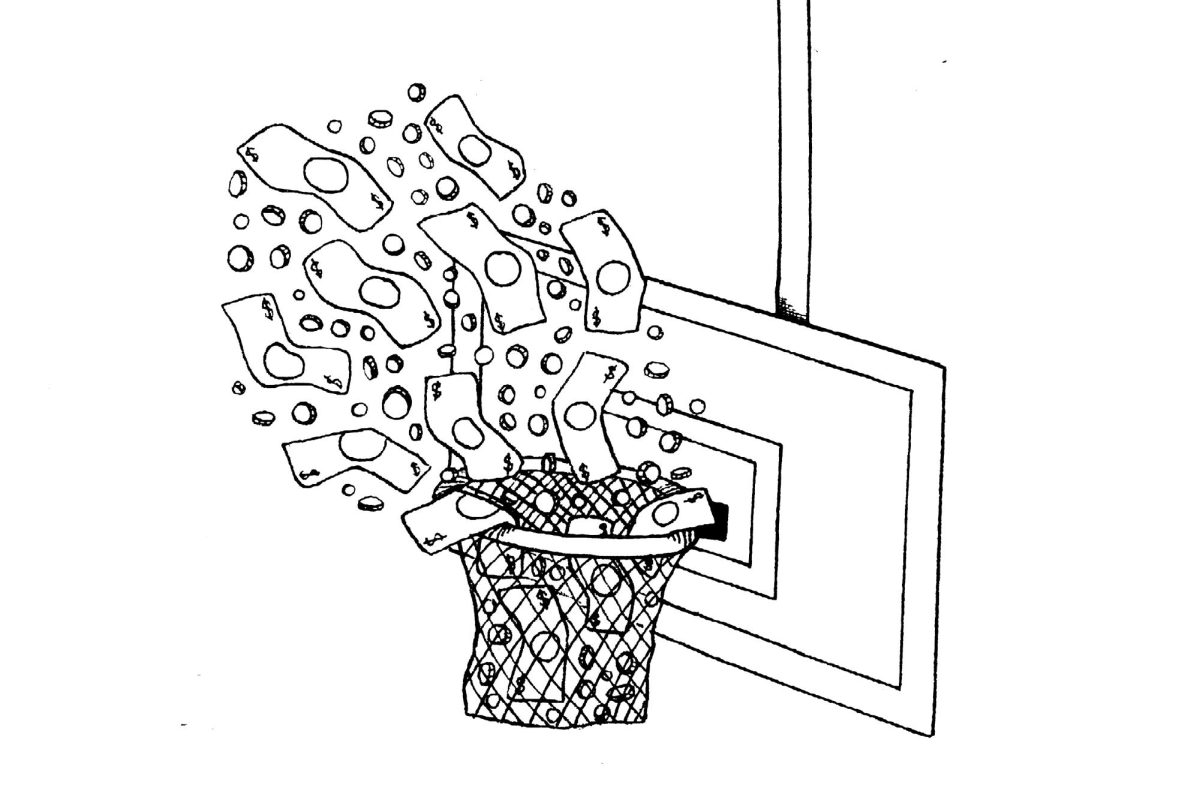

Affirmative action isn’t the problem – an already exclusive higher education industry that favors wealthier, whiter legacy applicants over others is. In 2011, The Hatchet reported that applicants with a parent who attended GW are 1.5 times more likely to be accepted into the University. So instead of litigating who among thousands of applicants deserves each and every crumb, the solution is to make the metaphorical pie bigger and admit more students of all backgrounds.

Still, the Supreme Court’s conservative majority stands poised to toss affirmative action into the dustbin of history. If they do, GW and universities across the country will have to reevaluate their admissions process, either salvaging their current one or preemptively recruiting more minority applicants through outreach programs, local recruitment offices and scholarship programs. The universities of Michigan and California have been barred from using affirmative action in admissions for more than a decade, and both university systems have struggled to enroll Black, Hispanic and Native American students at their respective campuses. Supposedly race-neutral admissions policies that result in single-digit enrollment percentages of minority students aren’t fair – they’re cutting students’ academic careers short before they can even start.

The University should seize this opportunity to explain how it evaluates an applicant’s race in its admissions process, recognize the members of its student body and put this anti-affirmative action hysteria to bed. Officials have yet to publish the results of this year’s University-wide survey of diversity, equity and inclusion at GW, but the future of its admissions policy is an early and urgent test of its values.

Desegregation marked the beginning of the end of one GW, but creating a diverse student body is a work in progress. Whatever the fate of affirmative action, wiping out prejudice – and acknowledging every facet of students’ identities – will always remain relevant at GW.

The editorial board consists of Hatchet staff members and operates separately from the newsroom. This week’s staff editorial was written by Opinions Editor Ethan Benn and Contributing Opinions Editor Riley Goodfellow, based on discussions with Research Assistant Zachary Bestwick, Sports Editor Nuria Diaz, Copy Editor Jaden DiMauro, Culture Editor Clara Duhon, Contributing Culture Editor Julia Koscelnik and Contributing Social Media Director Ethan Valliath.