Actor and TV star Matthew Perry received a standing ovation at the start of his live tell-all and dug deeper into his childhood, critical success and challenges of coping with his addiction in promotion of his newly released memoir.

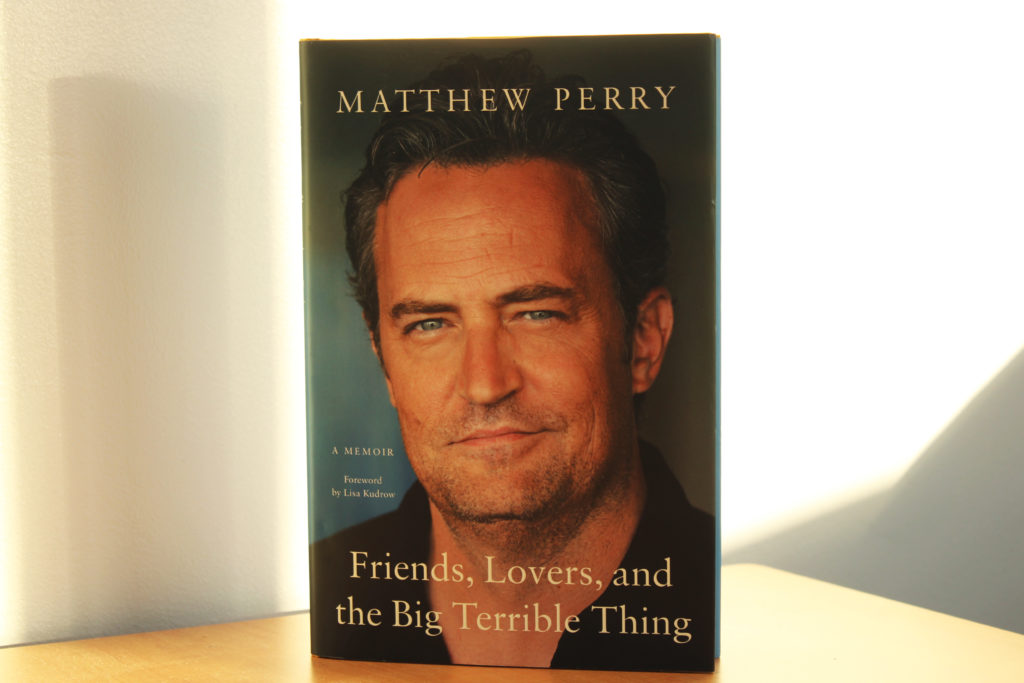

Perry said his goal to finish writing “Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing,” was to ensure that his sobriety would remain “safe,” while also providing hope to help other people struggling with the serious nature of addiction. The live interview marked the third out of four stops on Perry’s book tour and was led by New York Times journalist Lulu Garcia-Navarro last week at Warner Theatre downtown.

Perry rose to stardom playing the sarcastic but sweet role of Chandler Bing in the hit sitcom “Friends,” but performed on camera as early as 1991 during a guest appearance in the original “90210.” He nabbed two Emmy nominations for his dramatic portrayal of Associate White House Counsel Joe Quincy, a conservative lawyer who starkly contrasted the liberal staffers on “The West Wing,” all the while silently suffering from his double life of fame and addiction.

“I knew how I wanted to start it, which was this horrible night in my life,” Perry said of the start of his book. “I almost died. I wanted to tell that story and how I came out of that and how my resiliency and my strength that I didn’t really know was there came out and I was able to get better enough to be here.”

Before embarking deeper into the conversation about “the big, terrible thing,” Perry touched on growing up in the shadow of his accomplished parents – actor John Bennett and former press secretary of Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau Suzanne Perry – and his struggle growing up with divorced parents, who separated when he was only a year old. Perry said the original title of his memoir was to be “Unaccompanied Minor,” in reference to his frequent flights to Los Angeles to visit his father alone at the age of five and how he found comfort in gazing at the view of the city from a distance as he internalized reuniting with a parent soon.

Continuing the conversation on his complex filial relationships, Perry said his affinity for comedy stemmed from a desire for parental attention, even when it came to basic needs.

“I became funny as a result of my mother not giving me proper attention, sometimes crying, not feeding me,” Perry said. “When I would make her laugh, joke or fall down or whatever the funny thing was, she would be present and laughing and give me dinner which is what I really wanted.”

Perry and Garcia-Navarro shifted the discussion to Perry’s first encounter with alcohol and drugs and his subsequent descent into the “linear” nature of addiction, which he describes as only worsening as it continues. Perry said he felt all his problems drift away when he drank an entire bottle of wine as his first taste of alcohol at the age of 14 – a feeling he thought “normal people” experienced often.

“Nothing was wrong, fighting with my mother, being, feeling alone, none of that stuff,” Perry said. “I was just looking at the clouds, and it all went away and I felt wonderful.”

Perry said his experience early in his career as a young actor struggling to make it in Los Angeles further normalized the drinking culture and party life of the 1980’s, referencing his association with actor Hank Azaria and the Brat Pack – a friend group of famous actors – in his book. As his addiction continued, Perry said he always knew that “something was wrong,” as he continued to drink heavily even during the high points of his life, which pushed him to keep his struggles a “secret.”

“In that, my greatest moments, I would, in the back of my head, I’d go ‘why,’ and I say that in the book, ‘Why? Why can’t I stop drinking? Julia Roberts is your girlfriend! Why can’t I stop drinking? What’s the matter?’” Perry said. “It wasn’t until years later that I found out what was going on.”

When asked how he approached the character of Bing, Perry said he developed his cadence and line delivery in his youth with childhood friends Brian and Christopher Murray who would say things like “could this teacher be any meaner,” inspiring Bing’s sarcastic catchphrase that he eventually implemented in “Friends.” Yet even with the displays of “comedic genius” and rise to greater fame and success that came with the role of Bing, Perry said “the big, terrible thing” worsened as he continued to mask his addiction from his outward life.

“The toughest thing is having all your dreams and wishes come true and having it not fix what’s wrong with you,” Perry said. “I got the American dream. I got everything. I’m famous. I wanted to be famous really badly, and I enjoyed it for about six months. And then it fell off a cliff.”

Perry recalled transitioning to pills to further satisfy his addiction in secret, describing the lengths he would go to maintain his dosage of 55 vicodin per day. He said he would pretend to have a headache to receive pill prescriptions and attend various open houses to steal pills from medicine cabinets. Perry said his addiction was a “two-pronged disease,” split between mental obsession and a physical “allergy” in its pursuit to satiate itself.

Perry said eventually, “the big, terrible thing” became outwardly visible to his “Friends” costars, recalling that Jennifer Aniston first approached him in private out of concern because she and other cast and crew members could smell the alcohol on him. Then, at one point, he said 40 members of the cast and crew confronted him in his trailer and told him to “get help,” which he would agree to in the moment, but he knew there was no helping himself with his “fear-based addiction.” He said while people working on the show told him to get help, they left the responsibility up to him while they prioritized the continued production of the “money-making machine” of “Friends.”

Perry said he had to “lock” himself up by checking into rehab a total of 14 times when he felt fear take over. The actor, who has not had a drink since 2005, said he felt a desire for life and wanted to experience as much of humanity as possible, which sustained his perseverance.

“I got scared, and I thought, if I keep this up, I’m going to die,” Perry said. “And I don’t want to die because I haven’t learned everything there is on this land yet. And I want to learn. I want love. I want to have a child.”

Perry said a conversation with a spiritual leader during one of his first visits to rehab at 26 helped him internalize the nature of addiction as a disease and understand that his addiction was never in his control.

“He said ‘This isn’t your fault that this happened to you,'” Perry said. “And I went, What? What are you talking about? And it’s the first time I’d ever heard that.”

As Perry neared the end of his tell-all, he shared some words of wisdom with the audience that reiterated his message of relentless perseverance for anyone struggling with “the big, terrible thing.”

“You can get as far down on the scale and you can still come back from it,” Perry said. “Don’t give up. It’s not a death sentence unless you let it be.”