GW faculty and staff donated more than $275,000 in this year’s midterm elections to candidates and political action committees.

University faculty and staff donated nearly exclusively to Democratic congressional campaigns, which raked in 95 percent of employees’ donations, while Republican campaigns and other parties’ made up about four percent of donations. Faculty and staff donated $156,503 to Democratic congressional candidates in 2022 while Republican candidates reeled in $5,415 from employees, according to OpenSecrets.

“Being in D.C. has great influence on various individuals because there is much more discussion and information about the political issues that arise in Congress in the D.C. area,” Ann Ravel, the former chair of the Federal Election Commission, said in an interview.

Three Democratic political action committees – the Democratic National Committee Services Corporation as well as the Democratic Senatorial and Congressional Campaign Committees – received more than $84,000 from GW employees.

Faculty and staff contributed more than $17,000 to the reelection campaign of Sen. Raphael Warnock’s, D-GA, the largest amount given to a single candidate.

Employees donated the most to Rep. Lauren Underwood, D-IL, Rep. Tim Ryan, D-OH and Heather Mizeur – the Democratic challenger for Maryland’s 1st District – out of all Democratic House candidates, with a total of $32,084 in contributions between the three. GW employees donated just under $4,000 to GOP House of Representative candidates, with Zach Nuun, a candidate vying to represent Iowa’s 3rd District, receiving the highest donation of $2,000.

Professors in the Milken Institute School of Public Health donated the most of any school at GW with more than $8,300 to Democratic organizations and candidate campaigns, like Reps. Sharice Davids, D-KS, Lauren Underwood, D-IL and the Virginia House Victory PAC, according to data from the Federal Election Commission.

Professors from GW Law and the Elliott School of International affairs contributed a total of more than $4,650 to Democratic congressional candidates, organizations and candidate campaigns, according to FEC data.

Overall national donations for this year’s midterm elections are nearly $2 billion higher than those reported in 2018, which experts said is the result of a growing political divide.

Among the University’s 12 peer schools, New York University employees contributed the most to the 2022 midterms, totaling $1.6 million in donations, followed by the University of Southern California where employees delivered more than $560,000 in contributions so far this year. GW ranked seventh among its peer schools in donations, trailing behind Boston University, where faculty and staff raised more than $363,000, and outpacing Northeastern University, which surpassed $239,000 in contributions.

Experts in campaigns and finance said a university’s location might contribute to where their faculty donates because policy positions and ideological commitments may impact a professor’s contribution choice.

Ann Ravel, a board member of OpenSecrets and the former chair of the FEC, said faculty could be more politically involved because of GW’s location in D.C., which could result in more campaign donations than universities isolated from the political sphere. She said professors may be more likely to donate more money to state or local races rather than congressional elections because the candidates elected will more directly affect their lives as residents or employees in a certain area.

“I would assume that for state races for example, where probably the impacts are clearer on those professors or other employees who are working in the universities, that may be a place where they could have a little more impact,” Ravel said. “And I would assume that they might be contributing greater amounts.”

She said unlike this year, the share of presidential election contributions typically exceed those for midterm elections.

Total candidate and committee spending for the midterms is estimated to total more than $16.7 billion according to a report by OpenSecrets Thursday. Federal candidates and political committees are expected to spend $8.9 billion, and state candidates, party committees and ballot measure committees have raised about $7.8 billion.

The 2020 election broke records as the most expensive election in history to date with $14.4 billion in donations, while 2018 federal midterm donations totaled $14.5 billion when adjusted for inflation.

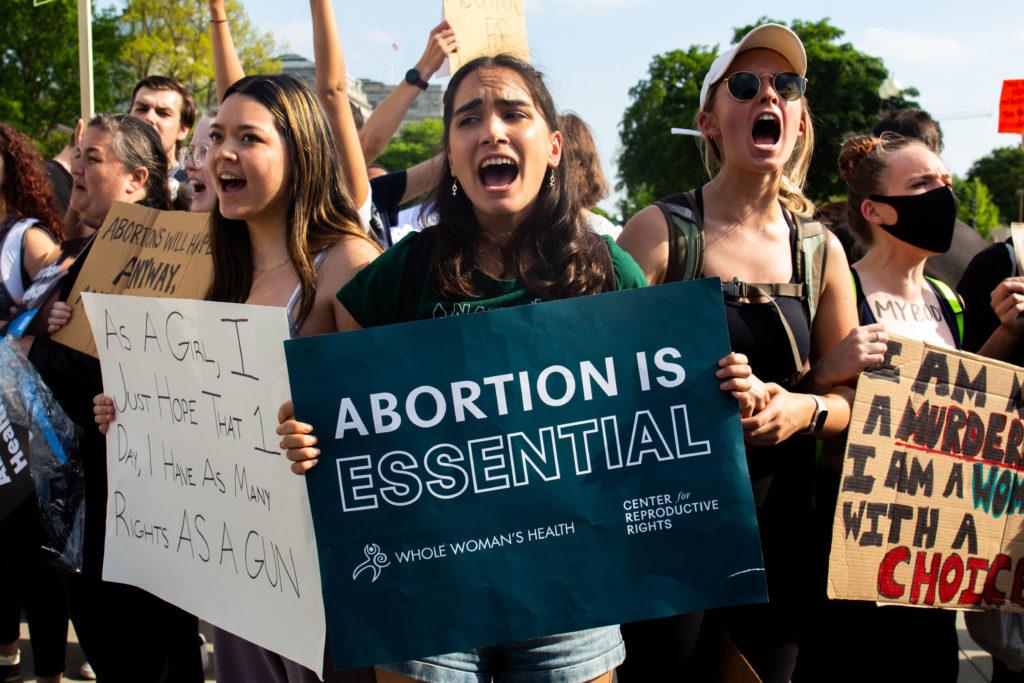

Ravel attributes the increase in contributions to the growth of political division nationwide, stemming from the 2020 presidential election denial and the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v. Wade, which she said created a “greater interest” in Congress’ decisions. Ravel said while individual contribution numbers are “interesting,” the majority of campaign funding comes from political action committees that “funnel” donors’ money to different campaigns.

“It is quite true compared to the rest of the country that people in D.C., all the way up from cab drivers to professors, are very involved in political issues,” Ravel said.

Mitchell Brown, a professor of political science at Auburn University and a GW alumna, said the opposing party of the sitting president typically wins midterm elections because the races highlight any “discontent” with the presidential administration, usually making governing harder for the remaining two years of the term. Republicans’ odds of winning back the majority in the U.S. House of Representatives are 83 out of 100, according to election data from FiveThirtyEight.

Brown said there is research suggesting that donations from academics tend to lean more Democratic, but partisan contributions ultimately depend on a professor’s field. The Center for Responsive Politics reported that employees from the highest-donating schools in the 2010 midterm elections — Harvard, Stanford and Columbia Universities — gave at least 75 percent of their total political contributions to Democrats.

“People do make campaign donations to candidates and other places,” Brown said. “That happens all the time, usually aligned with party or some other kind of ideological commitment or policy position.”