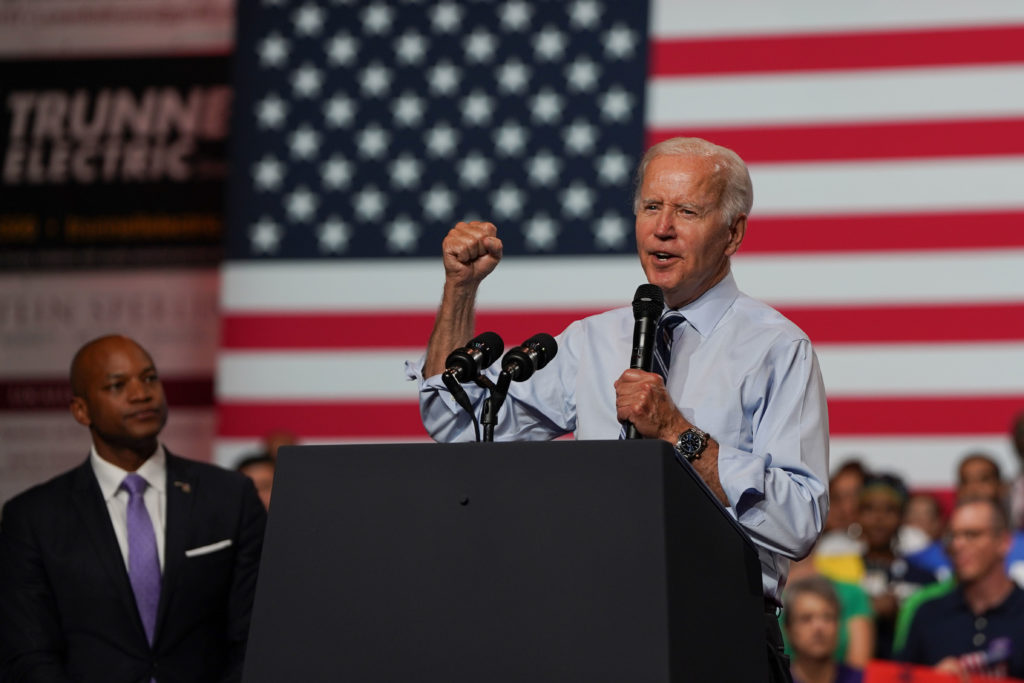

After President Joe Biden announced a $10,000 student debt cancellation for eligible borrowers, experts said the move could have gone further to equitably distribute economic relief to Americans.

In a move that will likely affect tens of millions of borrowers, President Biden announced Wednesday that the federal government will forgive up to $10,000 of student loan debt for individuals with an income below $125,000 and up to $20,000 of debt for Pell Grant recipients. Higher education and finance experts said while the program will relieve millions of Americans, the plan should more proportionally aid all Americans of different income levels.

The debt relief is intended to hold universities accountable for maintaining a “reasonable” cost of attendance and quality of education instead of maintaining a reputation for student debt, a White House news release states. Student loan borrowers received the option to pause monthly loan payments in March 2020 amid the COVID-19 outbreak, and the White House extended the pause through Dec. 31 last week in the federal order.

Steven Brint, a professor of sociology and public policy at the University of California, Riverside, said he is “skeptical” about the loan forgiveness program because the relief will be distributed to individuals from wealthier backgrounds who had the financial privilege of attending college, unlike their non-college-educated counterparts who may not have had access to the same opportunity.

“Unless it’s really targeted towards people who are struggling I don’t see the rationale for it myself,” Brint said.

Difficulty repaying student loans falls disproportionately on Black borrowers, who on average owe $25,000 more than white borrowers, according to a White House Initiative on Educational Excellence for African Americans study in 2016.

Higher education experts said the $10,000 loan forgiveness may not benefit GW students who have taken out larger loans given the nearly $80,000 cost of attendance.

“This plan offers targeted debt relief as part of a comprehensive effort to address the burden of growing college costs and make the student loan system more manageable for working families,” a White House release states.

Brint said a degree from private universities like GW provide a boost for post-graduate employment, but due to the competitive job market, some students might struggle to find a job in the five to 10 years out of college. He said income levels should determine the allocation of loan repayment programs to accommodate graduates who may not immediately find a job.

“There are going to be people who are going to be grateful for it, and there are certainly some people who will benefit and will get them on their feet,” Brint said.

Robert Toutkoushian, a professor of higher education at the University of Georgia, said the government should automatically determine who is eligible for the program and prioritize forgiving loans for borrowers who did not graduate because their incomes tend to be lower than college graduates.

“It is a thorny and debatable issue,” Toutkoushian said in an email. “There is no question that student borrowers will benefit from this program. People will always prefer to not pay for something.”

He said the student loan forgiveness program will place the responsibility of loan repayment on the public instead of students who take out loans because the program will use funding from federal tax revenues. He said taxpayers could possibly criticize the program for placing their tax money toward the debt of a student who opted to go to an expensive university like GW.

But he said Biden’s plan would also improve the economy because students will be able to more easily purchase goods and spend the money that they otherwise would have used to repay their loans.

He said applying for and repaying loans can be confusing for some students, and even with the cancelled debt, the federal loaning process will continue to pose challenges for students enrolling in higher education.

“Many students do not understand how loans and interest work and what the financial implications are of borrowing to pay for college,” Toutkoushian said.

In 2019, before the student loan repayment moratorium, about two percent of GW students who took out student loans were not able to repay them in fiscal year 2016, placing GW’s student loan default rate – the percentage of student borrowers who have outstanding loans within three years of beginning repayment – well below the national average of 10.1 percent.

David Schultz, a professor of political science at Hamline University and a professor of law at the University of Minnesota, said colleges and universities could use the forgiveness program to market their school’s affordability and possibly entice students who could not afford their cost of attendance, because mounting debt will be a less-severe obstacle.

“I think that may be one of the things that higher education is hoping for is that students who didn’t finish because of the affordability issue or people who they would like to lure back to college but can’t do it because of student loans or costs, maybe brings more students back at this point,” he said. “But that’s yet to be seen.”

Schultz said many borrowers will have to continue making regular payments in Jan. 2023 toward their student debt after the Dec. 31 moratorium expires, which could complicate transitioning back to a regular payment plan. He said the government could allow borrowers to discharge their debt when declaring bankruptcy to ease the burden of resuming loan payments.

“If we look at it from a broader perspective of, let’s say, trying to fix the cost of higher education then this doesn’t solve anything,” Schultz said. “It’s kind of like the Band-Aid on a much bigger problem that really still needs to be addressed in our society.”