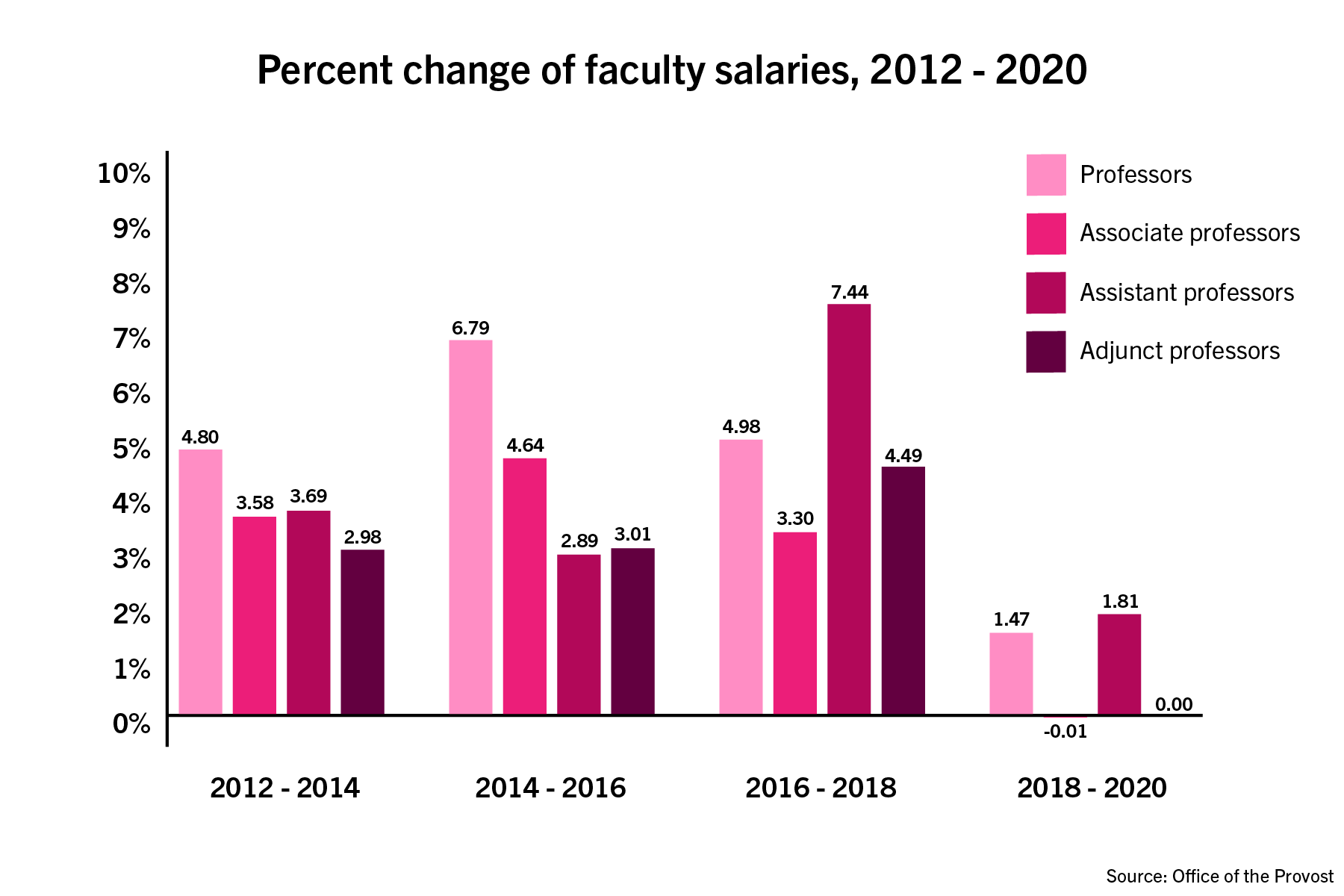

Salary increases for full-time faculty have outpaced pay raises for part-time faculty during the past decade – a trend adjunct faculty union members said they are trying to address in part-time contract renewal negotiations.

The University pays adjunct faculty with top degrees at least $4,467 for a three- to four-credit class – about 10 percent more than the $3,915 course minimum they were paid in 2011 – but the increase lags behind about the roughly 19 percent jump for full professors and 17 percent jump for assistant professors in the same period. Part-time professors said the University’s adjunct faculty union is wrapping up yearlong negotiations with GW in an effort to come to an agreement to increase their pay and benefits and improve academic recognition among adjunct faculty.

Associate professors have seen their average salaries grow by about 11 percent during the same period as full and assistant professors, according to GW data.

Kip Lornell – the head of the adjunct faculty union and an adjunct professor of music, history and culture – said the contract the union is negotiating to establish “equity” for part-time faculty compensation through increased pay, professional experience recognition and added benefits for part-time faculty.

“We’re trying to get rid of those inequities,” he said. “We’re trying to make it a fairer place to work, and the University basically just puts a thumb down and said ‘We want status quo.’”

The adjunct union negotiates a collective bargaining agreement with administrators every few years to improve pay and benefits for part-time faculty on campus. Adjunct union leadership and representatives from the Service Employees International Union, which represents GW’s adjuncts, negotiate a new CBA when the previous one expires.

On average at GW, full-time professors earn $186,000, associate professors earn about $118,000 and assistant professors earn about $101,000, according to GW’s Core Indicators Report on students and faculty academic affairs. The University’s regular part-time faculty – returning adjunct professors who hold the highest degree possible in their field and have additional responsibilities like advising or assisting with their department – receive a $24,683 salary, according to the CBA between 2019-21.

Nicholas Anastacio | Graphics Editor

Howard University adjunct and non-tenure track faculty threatened to strike last month until coming to a tentative labor agreement with Howard officials to increase pay and access health insurance. American University students and faculty demanded officials increase wages amid ongoing adjunct faculty union negotiations during a protest last month.

Lornell said the union wants to increase part-time faculty pay to align with GW’s peer schools in the area, like Georgetown University, which pays adjuncts significantly more than GW for the standard three- to four-credit classes.

Georgetown’s minimum adjunct faculty pay has increased each year since 2017, and as of 2019, totaled about $7,000 for a course of three or more credits, according to Georgetown’s 2017-20 CBA.

Lornell said GW’s individual adjunct faculty requests for pay raises are oftentimes denied, so most adjunct faculty – even those with years of experience at GW – are only paid the CBA’s minimum salary or slightly above.

Adjunct faculty can receive a roughly $190 yearly pay increase if they have a terminal degree – or the highest degree in their field, like a doctorate or juris doctor degree – while those without a terminal degree receive only a $167 increase, according to the 2018-21 CBA.

“If you ask for a raise, the answer is almost always, ‘We can’t afford it,’” Lornell said. “We want to put a system in place where it recognizes excellence, years of service and professionalism.”

University spokesperson Tim Pierce declined to say how officials determine pay raises for adjunct faculty, what salary adjunct faculty members have been paid during the past five years and what non-pay benefits adjunct faculty receive. Pierce also declined to say how the pandemic impacted the hiring of part-time faculty and how peer schools’ pay rates help determine GW’s adjunct faculty compensation

“The University continues to appreciate all the hard work its dedicated part-time faculty provide to GW, especially during a challenging pandemic and is hopeful that resolution on a new agreement will be reached soon,” Pierce said in an email.

GW’s 2018-21 collective bargaining agreement includes a “no strike/no lockout” clause, which bans all union leadership and all adjunct faculty from participating in any strike that disrupts “normal operations” of the University.

The adjunct faculty union represents all part-time faculty members at GW who are all automatically enrolled in the union and given the option to pay an increased rate to be a full SEIU union member. The union negotiates new CBAs with officials and offers discounted insurance and health care to all full union members.

Jill Brantley, an adjunct professor of sociology and a member of the adjunct union, said officials can more easily adjust the number of adjuncts when planning courses than full-time faculty because most adjuncts are on short contracts.

Adjunct faculty teach about 42 percent of GW’s courses, while full-time faculty teach about 58 percent of the courses, according to the Core Indicators Report. GW employed about 100 more part-time faculty members than full-time faculty members in the 2020-21 academic year, according to institutional data.

Brantley said while full-time faculty members have other University responsibilities, like conducting research, bringing in grants and performing other institutional service, part-time faculty are expected to produce the same quality of instruction as full-time faculty but with less compensation.

“The work is exploitative, if you measure what an adjunct faculty member gets paid for a course, and we are expected to deliver at the same quality as the full-time faculty member,” she said.

Ashley Le, an adjunct professor of journalism in the School of Media and Public Affairs, said she spends extra time outside of the journalism capstone class she co-teaches answering questions in office hours, grading assignments and giving students extra assistance with their video projects.

“I would say that every week, especially the week when projects are due, I would spend almost every evening, Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, whenever I have time, to come in to do one-on-one lessons on editing, to give help to students,” Le said.

Ellen Zavian, a member of the adjunct faculty union and an adjunct professor of law, said students view adjunct and full-time faculty as the same resource and will go to both of them for the same assistance with letters of recommendation and career advice. Zavian said administrators are not receptive to the problems all adjuncts face, and there is no official mechanism like the Faculty Senate for adjuncts to report their struggles.

“We’re trying to bring it to them – this is what’s happening,” she said. “And the response we’re getting is, ‘Well, is that only one person or is it 10 people?’ and we’re just saying, ‘This is what our membership is coming to us with.’”

Zavian said it takes months to prepare a class for students, and in the case that students have additional questions, adjuncts also have to stay up to date on all the current events happening in their respective field, which is extra time they are not compensated for. She said adjuncts also do not have control of their own classes, so officials can increase class sizes or cancel classes without consulting the adjunct professor.

“I’m not part of that conversation,” she said.