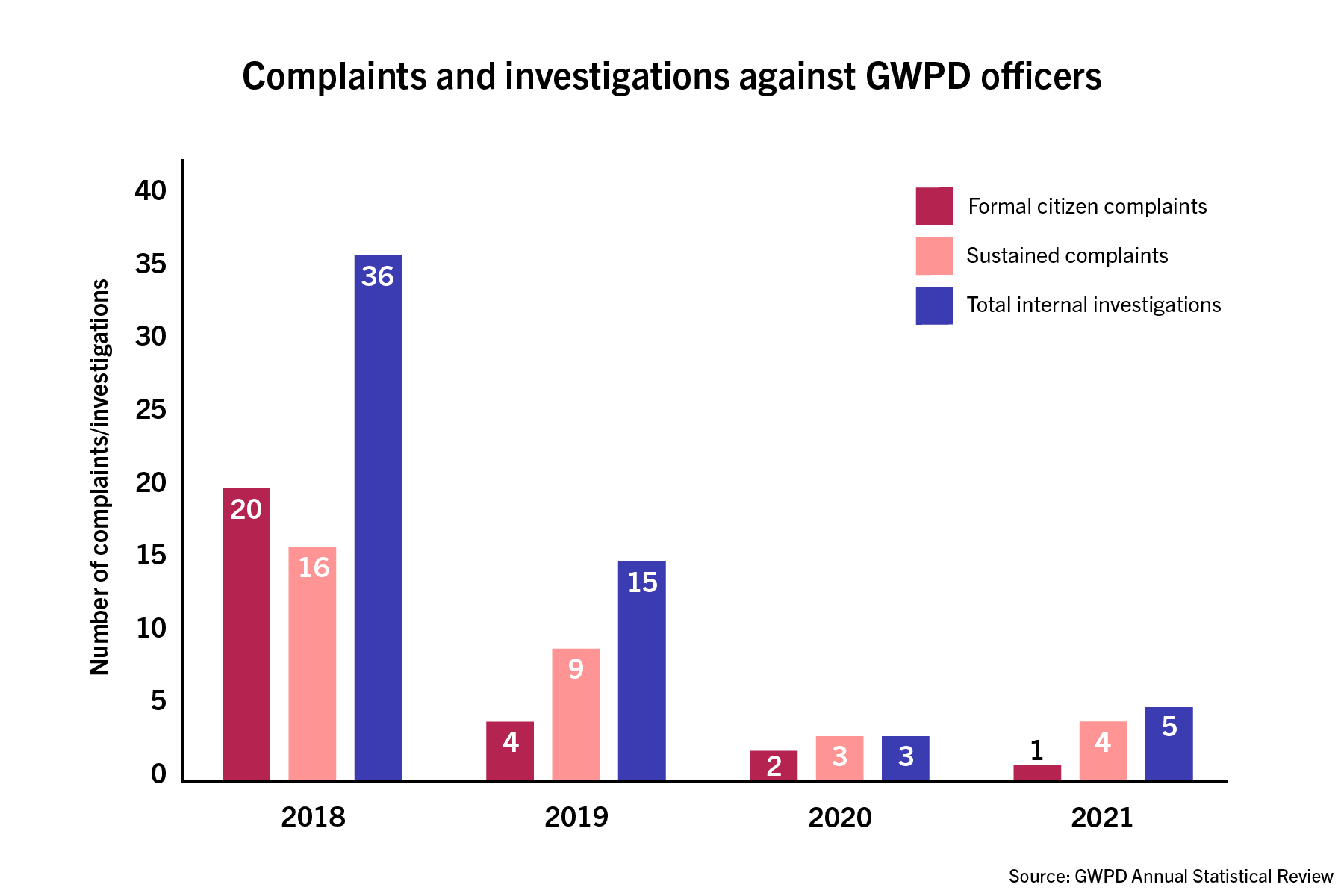

The number of complaints against officers and internal investigations at the GW Police Department remained low among the past four years after a resurgence in campus activity amid the University’s COVID-19 reopening.

The GWPD Annual Statistical Review, which the University debuted last year, reports that GWPD performed five internal investigations, recorded one citizen complaint and registered four “sustained complaints” – officer violations that result in departmental action – in 2021. The report shows similar totals to when the department recorded three violations and three investigations in 2020, a year when crime in Foggy Bottom dropped dramatically as students left campus following the initial outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The numbers mark the second straight year of a major downturn in complaints filed against GWPD officers, despite the surge of campus activity during fall 2021 when the University completed its phased reopening. The report states that GWPD recorded nine violations and 15 investigations in 2019 after registering 16 violations and 36 investigations in 2018 – totals that GWPD Chief James Tate called “very high” during an interview last year.

Between 2018 and 2021, the number of violations among GWPD officers dropped by nearly 69 percent, and the number of investigations plummeted by more than 85 percent, according to GWPD data. Tate attributed GWPD’s 36 investigations in 2018 to management and human resources issues within the department, like investigations into officers who regularly showed up to work late.

Nicholas Anastacio | Graphics Editor

Tate said reforms he’s implemented since joining the department in 2020, like improved de-escalation training and body-worn cameras, have improved GWPD’s relationship with students.

“We’ve also increased GWPD’s efforts regarding community engagement in an effort to create positive relationships and to be viewed as a resource to our students, staff and faculty,” Tate said in an email. “We also believe implementing the use of body-worn cameras increases transparency and accountability, which builds trust with our community.”

Tate said GWPD investigated cases of improper language, negligence, an improper search, a “search and seizure” violation and an “arrest and detention” violation in 2021. He said each investigation led to corrective action, like additional training or disciplinary action or a combination of the two.

“We’ve enhanced training at the officer and supervisor levels, which leads to officers exercising better judgment when interacting with the community,” Tate said.

Tate organized two 40-hour, weeklong training sessions in 2020, with 18 focus points that included defense tactics, unconscious bias training and de-escalation skills meant to improve community interactions. In November 2020, Tate said the department would require “a higher level of training,” moving exercises to Maryland-based police academies that offered more than twice as many training hours.

The report states GWPD responded to 6,403 calls for service in 2021 – an uptick from the more than 5,700 calls in 2020 but fewer than the nearly 15,000 in 2019. Tate said he is still “mindful” of the effects the pandemic had on the year’s statistics.

Some students credit Tate with the drop in investigations after he reformed departmental policies upon his arrival at the University, which came on the heels of a tumultuous turnover within the department in 2018, when GWPD’s chief and assistant chief both resigned.

GWPD arrested 32 people in 2021 – six more than during 2020 but 16 fewer than in 2019, according to the report. Only one outside person filed a complaint against GWPD in 2021, down from two in 2020 and four in 2019.

“Leadership starts at the top, and I have to model that behavior that I expect our officers to model,” Tate said in an interview last year. “And then, of course, I expect that type of behavior and interaction with the community to permeate all the way through our department.”

Junior Kylie Foster, the chief of staff of the Black Student Union, said Tate’s leadership and cooperation with students are partially responsible for the overall reduction in GWPD’s investigations in the last two years.

“I think there’s a lot of factors included in it,” she said. “But I think it has started with Tate being in the position that he’s in, and I think he’s done a good job.”

Foster said Tate has improved GWPD’s relationship with BSU with regular meetings meant to increase transparency. She said BSU members discuss any issues they have with safety on campus – like restricting residence hall access to delivery drivers – as well as Tate’s performance as chief and how GWPD can connect with Black students on campus.

GWPD started to build its relationships with student organizations under Tate’s leadership and increase department transparency in 2020 amid a nationwide conversation about police brutality against Black people.

Since then, GWPD has rolled out body-worn cameras and started releasing annual statistics that show the demographics of stopped pedestrians. Tate has also consistently met with the Student Advisory Board, an organization of undergraduates who work with GWPD to present potential policy changes to policing on campus.

“It seems that they have a good head on their shoulders,” Foster said. “They’re going to do everything they can to learn, unlearn and relearn, everything they can to show up for the GW student body.”

Freshman Witt Kolsky, a member of the Student Advisory Board, said Tate’s reforms, like the body-worn cameras and increased training, have improved the quality of GWPD’s policing and its connection with the student body, leading to fewer complaints against the department.

“I know he works very hard so he is always open to students’ gestures,” Kolsky said of Tate.