Nestled on the first floor of the Science and Engineering Hall, GW’s public health lab translates community members’ bi-weekly COVID-19 nasal swabs to online test results, generally in the span of 24 to 36 hours.

Working behind the scenes, a dozen technical staff members conduct, process and report up to 3,000 tests on a daily basis. The Hatchet met with the faculty spearheading the lab’s operations and took a tour of the space to see the workings of the system at the center of the University’s COVID-19 response.

From the H Street testing trailer to your Colonial Health Center portal, here’s how GW’s public health apparatus processes your COVID-19 test:

From the test tube to the CHC portal

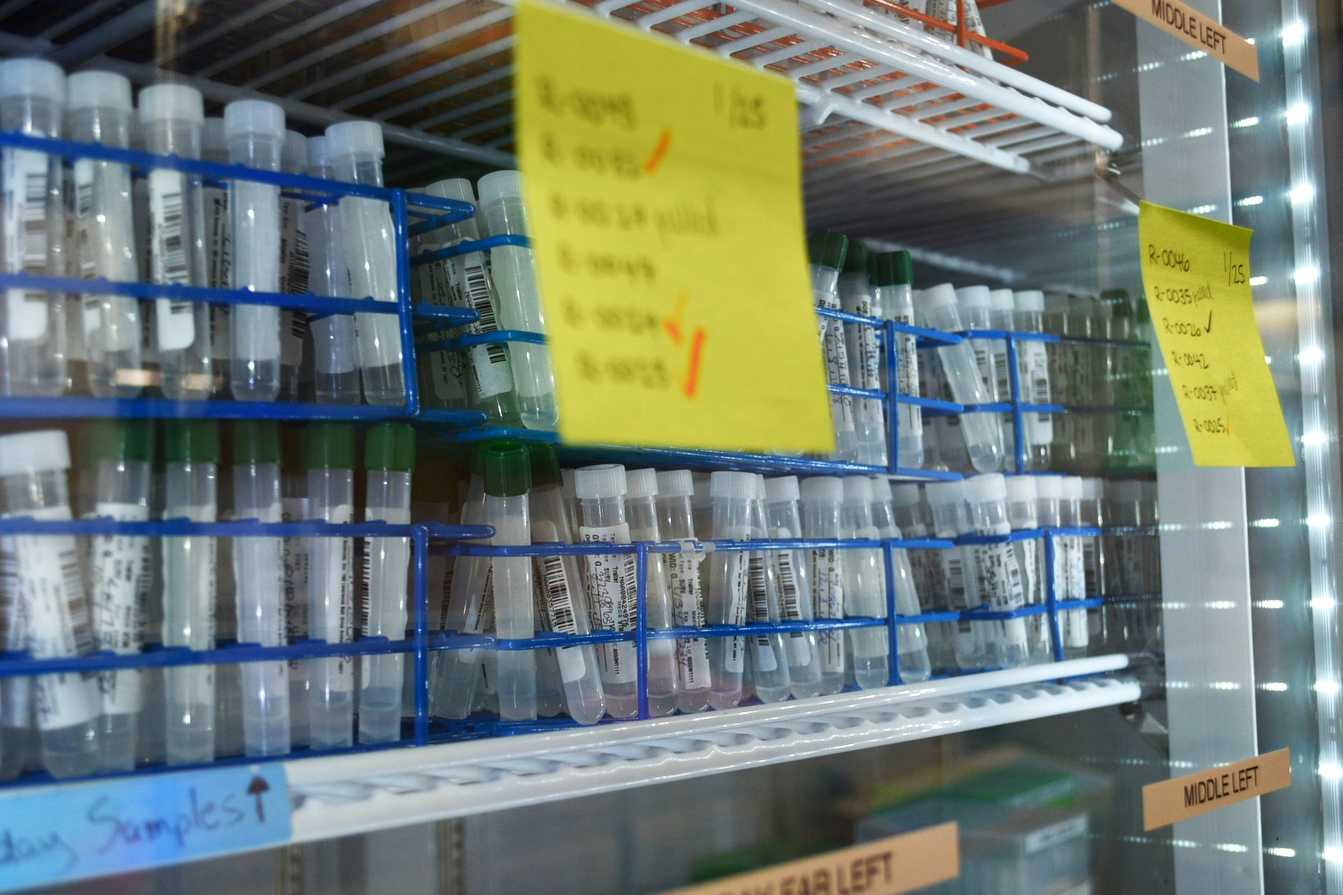

Praveena Tummala, the lab’s director of laboratory operations, said staff start to receive COVID-19 tests from GW’s testing centers at about 8 a.m. every weekday. The tests first arrive in a processing room.

Tummala said lab technicians manually de-cap each test tube and extract a small amount of the tube’s liquid onto a section of a 96-well plate, a rectangular plastic dish with 96 holes to hold liquid samples.

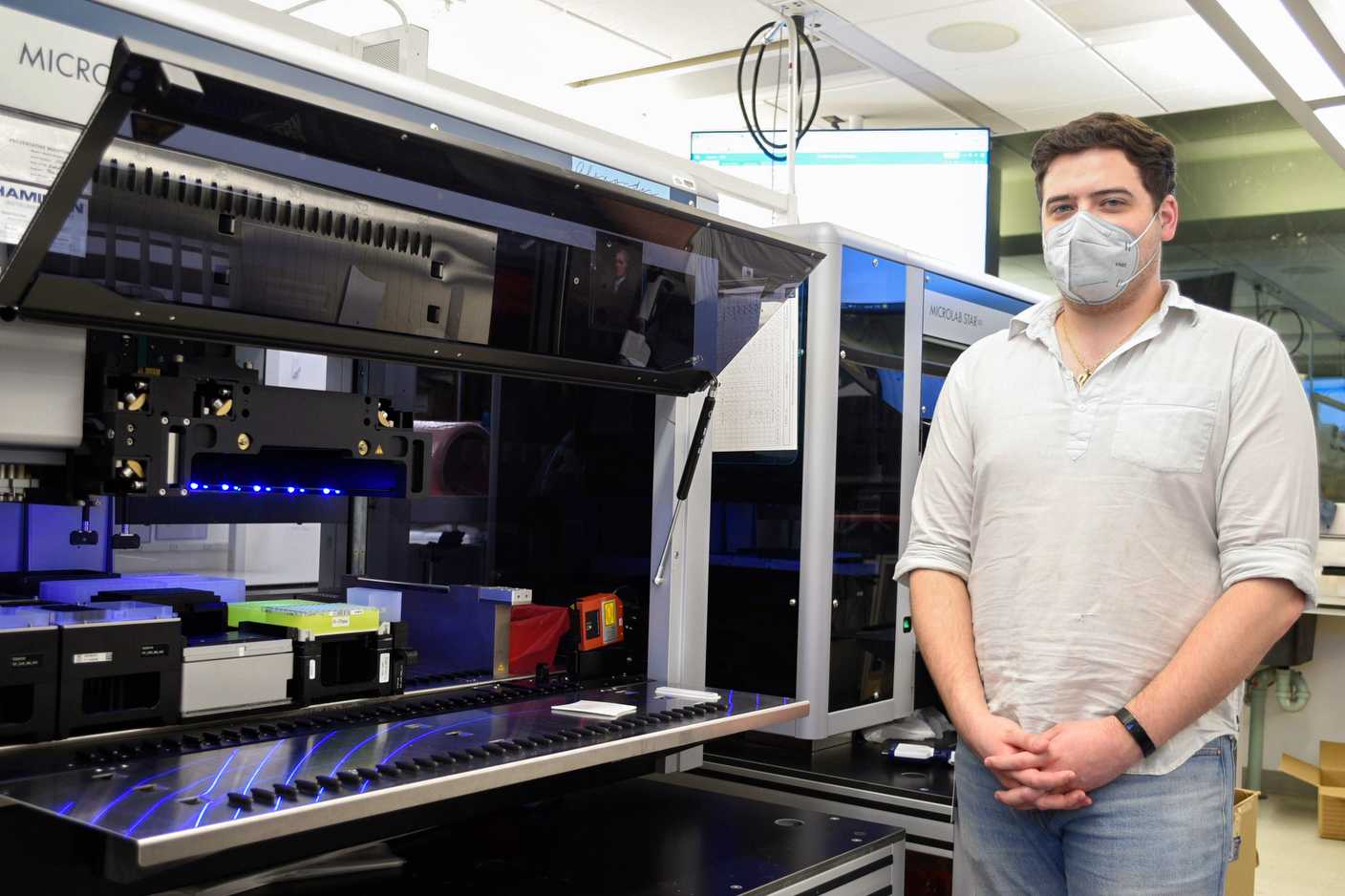

Next, she said Hamilton Microlab STAR robotic machines dispense chemical solutions into each sample on the plate, scan the plate and kill any parts of the samples that do not contain the live coronavirus.

Danielle Towers | Assistant Photo Editor

Lab staff said the processing room machines take up to two hours to extract both viral and human RNA from each of the plate’s 91 individual samples and five control samples, which provide a quality measure to ensure reliable results.

Before technicians transfer the samples to the main lab room, each is decontaminated to prevent exposing potential coronavirus RNA to other areas, Tummala said.

“Only the samples after everything is killed is brought outside,” she said.

Jack Villani, the lab manager, said technicians ensure each sample complies with specific criteria before they are moved, a step he called the most labor-intensive task of the day.

Danielle Towers | Assistant Photo Editor

In the lab’s main room, Villani said the Microlab STAR robots use pipettes to distribute a chemical liquid that breaks open every cell and virus particle in each sample. He said after each sample is removed of contaminants, lab staff prepare the samples for the PCR test.

He said a Mosquito LV robot transfers the combined samples to another 96-well plate that contains chemical solutions required for PCR testing.

“What’s in that water is dissolved RNA, and that’s what we actually use for PCR testing, so all of that has to happen before we can actually do the actual test to see if any virus is present,” he said.

Villani said the PCR test detects two regions in the coronavirus gene, known as N1 and N2 primers. A positive result means a sample tested positive for both the N1 and N2 primers, while an inconclusive result means the sample tested positive for only one of the two.

To examine the reliability of the result, Villani said staff assess each sample’s amount of human RNA. An invalid result is reported when the amount is too low, requiring a second PCR test.

Villani said the assessment of a single plate usually takes five minutes to complete. He said the entire process takes a total of six to eight hours from start to finish.

“We upload the data into our lab information system that finalizes the results, and then that system reports back to Point and Click, which is the school’s health record,” he said.

Hiring, retaining and assisting staff

Tummala, the laboratory operations director, said hiring additional staff members like lab assistants and supervisors has been a struggle because the positions are temporary and must be filled when a staff member’s term concludes. During an interview with The Hatchet in December, officials said they would increase the number of people staffing the testing operation to deal with the influx of testing appointments in January.

“The staffing has always been challenging, and even right now we are not fully staffed,” Tummala said. “We don’t have supervisors currently, so it has been quite challenging.”

Tummala said she created more part-time positions in the lab and hired two graduate students and three undergraduate students to help run tests. She said the lab team had about 15 staff members at its maximum in August but is currently made up of 12 lab assistants, associates and associate leads.

“Since we came back from the winter break, we had times when we had to work through the weekends, and our staff graciously stayed back and came on extra days,” Tummala said. “I think everyone who works here currently takes pride in doing what we do, so it’s an extremely great team.”

The University’s job postings website currently includes listings for a supervisor and a laboratory assistant for the lab.

Danielle Towers | Assistant Photo Editor

Villani said automation in the lab, like the Microlab STAR robots, made processing large amounts of samples easy to execute and reduced staff’s physical exhaustion from repeatedly conducting the same tests and procedures.

“I think our team has always been very proud of what they do, and seeing that increased productivity I think has made them happy,” he said.

Home test kits and the future of the pandemic

Villani said the Food and Drug Administration approved the lab to create and distribute home testing kits for the University community earlier this month. He said the lab designed the kits to fit with the lab’s test processing workflow without much disruption.

He said the staff plans to primarily distribute the home testing kits to testing locations like the Virginia Science and Technology Campus to determine the kits’ reliability and their potential use on a greater scale.

Tummala said the lab team is working to improve the processing workflow to share results more quickly to University community members. She said the team is trying to extend its work hours on Fridays – apart from the normal 8 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. and 12:30 to 9 p.m. shifts on weekdays – in hopes of accelerating community members’ results.

“We’re just trying to extend our hours a little bit,” she said. “Maybe start a little early so that way we can test and release more results throughout the day.”

Tummala said the University community’s positivity rate has improved in the past few weeks, returning to the two to four percent range from before the spread of the Omicron variant. She said while campus health is improving, she thinks another COVID-19 variant could possibly sweep across the District once again.

“Whatever it is, we are prepared to keep our GW community safe and keep testing,” she said.