Elliott School of International Affairs researchers are continuing to track countries’ ability to govern data in areas like human rights through an online interactive map as they start the third phase of an ongoing study.

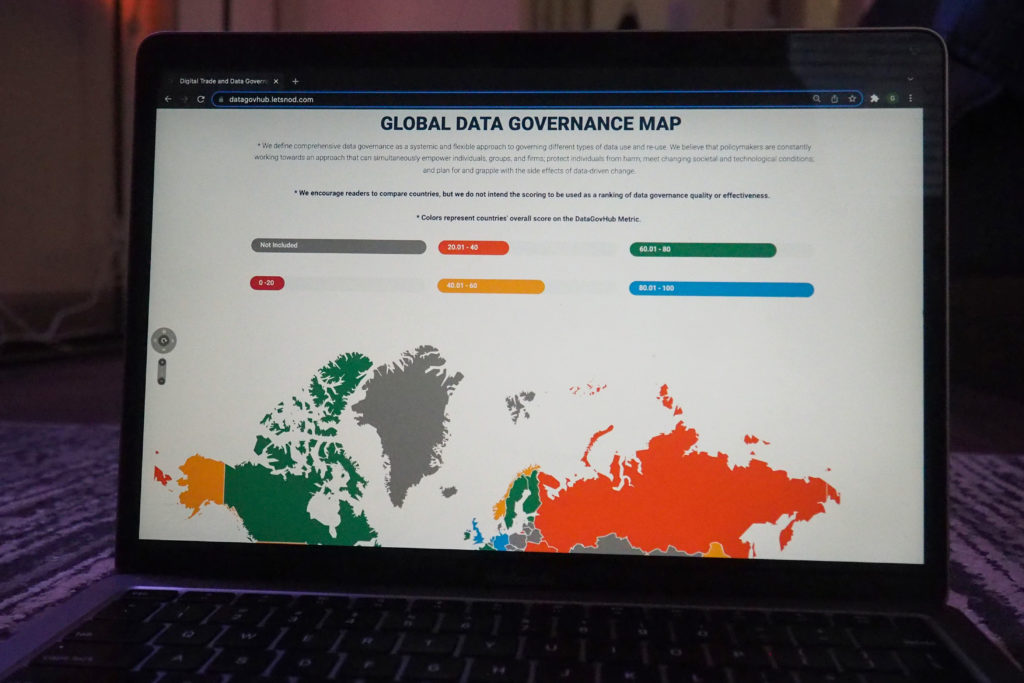

The Digital Trade and Data Governance Hub launched the Global Data Governance Mapping Project last May, and the team has completed two phases analyzing how nations are implementing policies and laws related to data governance – how countries enforce regulations and standards to manage and protect data, according to the project’s website. The research team will study more countries, collect documents about their data policies and expand its range of “indicators” to assess data governance across the globe during its third phase, according to the report on the project’s first year.

Susan Aaronson, the director of the hub and a research professor of international affairs, said the project organizes how different countries plan strategies to handle issues like human rights and national laws to assist policymakers in developing international standards for data governance.

She said addressing issues related to data governance can help with handling other problems like the potential international decline of democracy and climate change.

“I’m not saying data governance is more important than climate change, but I’m saying that if we can figure this out, we might be more successful in these other realms,” she said.

The project observes six attributes of data governance that value a nation’s strategic, regulatory, responsible, structural, participatory and international plans when it comes to data, according to the first year report.

The research team assigned numerical values to nations that fulfill criteria in each of the six attributes. Australia scored a 75 in the responsible attribute – a measure of a nation’s consideration for the implications of data governance on human rights – because it lacked the digital charter indicator – a government’s formal statement that recognizes its responsibility to uphold data governance principles, according to the project’s website.

Aaronson said richer nations like the United States did not consistently receive high scores, and national histories – including potential invasions of privacy – could do much more to influence data than wealth. Readers are encouraged to compare national scores but should understand that they are not rankings of countries’ effectiveness when it comes to data governance, according to the project’s website.

She said researchers analyzed how 51 national governments and the European Union handle data governance based on the six attributes in the first phase. She said recent grants will fund the staff members’ observations of 19 more countries, expanding the total number of countries on the map to 70.

She also said while future research will incorporate eight more factors to evaluate nations, the team is concerned that adding more indicators will make it more difficult to assess each nation’s overall performance.

“Funding is a challenge right now,” she said. “We are doing okay, but fundraising for this kind of thing is hard. It’s never easy.”

Aaronson said the data governance hub plans to hold study groups to educate trade officials from the United States, Canada and the United Kingdom on the project’s findings and hold further discussion on data governance next month.

“Changing the internet is changing the world,” she said. “It changed the economy and now it’s changing what we research, how we teach and when and what we teach.”

Experts in data informatics said the project is an accessible compilation of various data governance factors that can help national governments determine which attributes need improvement to better democracies.

Jim Samuel, the executive director of the informatics program at Rutgers University’s Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy, said the principle behind the data governance consists of national governments respecting individuals and entities’ rights associated with data like images and statements.

He said the project can analyze whether data ownership in countries is protected and motivate national governments to behave more responsibly with data governance strategies.

“If in the process of gathering this information, we are able to collect information on best practices that are implemented at various points around the world, then it might be interesting to take a careful look at those best practices and analyze where it is that the true owners rights are being protected,” he said.

Angie Raymond, the director of the Ostrom Workshop Program on Data Management and Information Governance at Indiana University, said the website uses little academic jargon, making it easy for users to understand which data governance trends are emerging in various countries.

“You can literally go to this map and say, ‘Look, here are all of the countries that are actually thinking about data governance as something that has to be part of a strategic plan,’” Raymond said.