Milken Institute School of Public Health researchers conducted a study on how air pollution has affected Black mortality rates in D.C. that has garnered national attention.

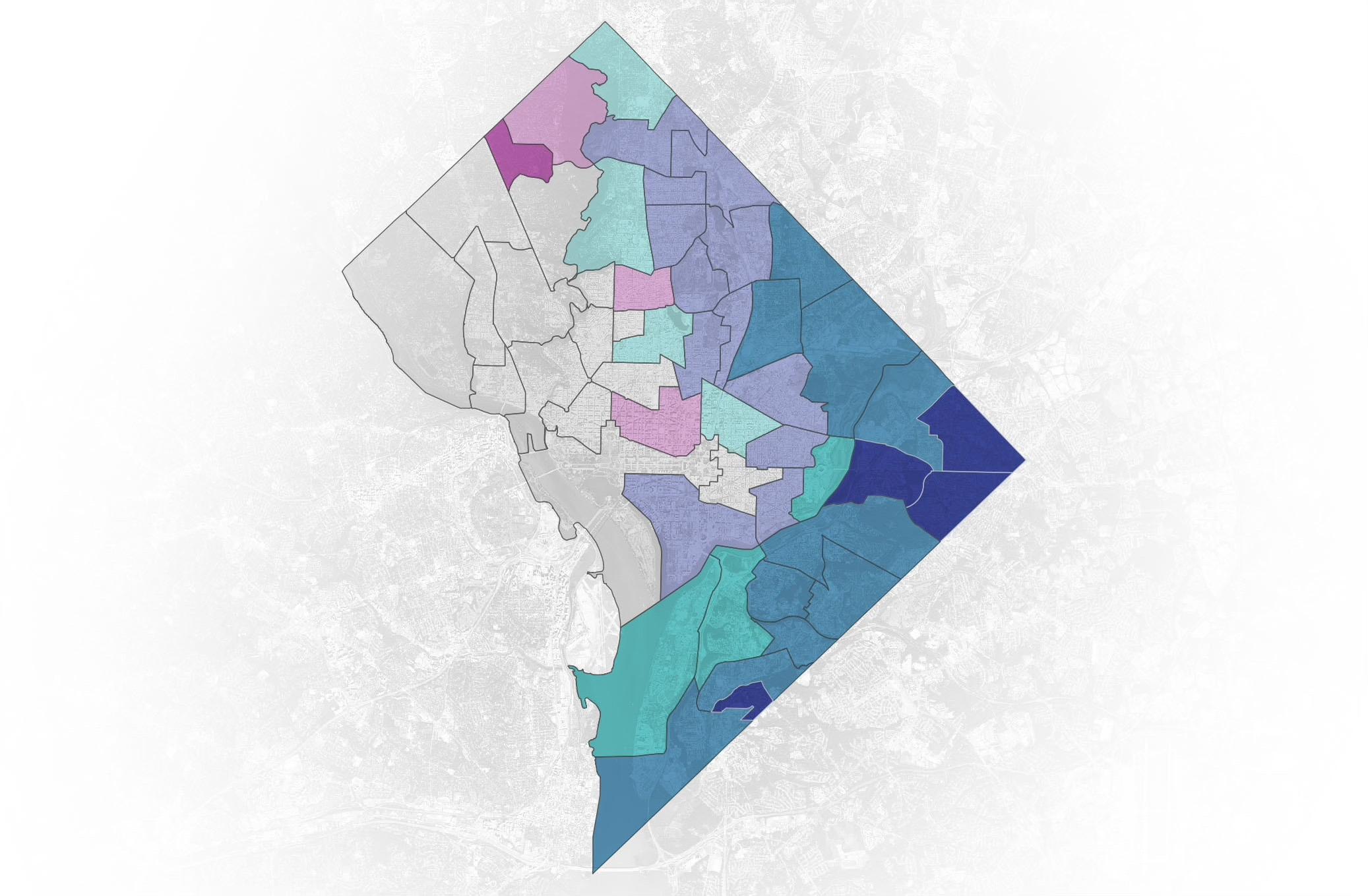

NASA posted an online map displaying how air pollution has affected Black mortality in the District earlier this month from a study that a Milken professor conducted this fall. The October study on air pollution and related health implications, like cancer, showed that wards 7 and 8, which make up the majority of Southeast D.C., were home to the highest concentrations of PM 2.5, an air pollutant detrimental to human health.

Susan Anenberg, an associate professor of environmental and occupational health and one of the paper’s authors, said the study found that even though air pollution levels across the District have declined, the pollution’s related health risks remained “inequitably distributed,” which the researchers indicated on the study’s map of D.C.’s neighborhoods.

“We explored the inequity and air pollution related health risks across Washington, D.C. at the neighborhood scale,” Anenberg said in an interview. “And this is novel because most other studies that have explored air pollution have equity have really stopped exposure, so they’re looking at the difference in air pollution levels at the neighborhood scale and comparing concentrations of pollutants to each other. We took that a step further and also considered population vulnerability.”

The Earth Observatory, a NASA website that publishes global maps and shares research on the Earth’s climate and environment, featured the map as its “image of the day” online earlier this month. The Earth Observatory publishes images each day, capturing events like severe flooding in the Pacific Northwest and increased fire activity in India.

The image of the District’s map colored neighborhoods with more air pollution and higher Black populations dark blue. Southwest D.C., which has a higher Black population compared to the Northwest, recorded the highest levels of air pollution.

Courtesy of NASA

Anenberg said the study found higher rates of PM 2.5-related health risks in neighborhoods where communities faced lower educational attainment and a lower household income. She said the research team used satellite imaging and air quality sensors, which measure air pollution particles on the ground, to create a clear picture of pollution in the District.

Anenberg said while studies in the past have examined differences in air quality throughout D.C., this is the first systematic study that also explores air pollution’s correlation to health inequities. The study found that air pollution in the District led to 220 cases of excess all-cause mortality, 90 cases of ischemic heart disease, 20 cases of lung cancer, 10 cases of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and 10 stroke deaths annually.

Mortality rates attributed to air pollution particles are more than four times higher in ward 7 than in wards 2 and 3, which have a smaller percentage Black population, according to the study. Anenberg said the neighborhoods where air pollutants elevate mortality rates face 10 percent lower education and employment rates.

The study found that the rates of poverty and education and employment are 10 percent lower, and residents earn a medium household income that’s $61,000 less in wards 5, 7 and 8 than wards 1, 2 and 3. Wards 5, 7 and 8 have the highest PM 2.5-attributable all-cause mortality rate, and wards 1, 2 and 3 have the lowest.

Anenberg said the District only has five air quality sensors, so the researchers relied on satellite imagery to fill in the missing data on air pollution particles.

“We used a combination of satellite remote sensing with ground observations to explore not just how neighborhoods compare with each other in terms of air pollution related health risks, but how those risks have been changing over time,” Anenberg said.

Anenberg said air pollution has declined in the District as a whole because of regulations like the Clean Air Act – which restricts pollution in states from the Midwest, where consistent winds carry emissions to the District – and regional controls that limit emissions from industrial activity in the immediate D.C. area.

“Air quality in D.C. is heavily impacted by emissions from upwind states,” Anenberg said. “For example, coal fired power plants and industrial plants in the Midwest have a large impact.”

Elena Austin, an assistant professor of environmental and occupational health sciences at the University of Washington, said local pollution sources also drive up levels of PM 2.5 in the neighborhoods’ air. Austin said lower income neighborhoods are closer to major sources of local emitters that increase air pollution.

“Increased proximity of lower income neighborhoods to important sources of PM 2.5 including roadways, train yards, industry sources and other transportations emissions such as aircraft and ships,” Austin said in an email. “Previous work has demonstrated that in the U.S., communities of color experience systematic increase in exposure.”

Austin said the results of this study can lay the groundwork for lower income communities to advocate for action to improve air quality.

“This study has the potential to empower communities to demonstrate their need for mitigation, including increased efforts to reduce emissions, community led air quality sampling and indoor air quality improvements,” Austin said.

Jesse Berman, an assistant professor at the University of Minnesota School of Public Health in the Division of Environmental Health Sciences, said the study’s map of the District, featured as NASA’s image of the day, is valuable because of the relationship it displays between mortality rates from air pollution and the percent of the Black population in different D.C. neighborhoods.

“What this is showing is that there is a far greater proportion of neighborhoods in Washington, D.C. that are both a majority Black as well as have the highest PM 2.5 mortality rate,” Berman said.

Berman said air pollution is linked to a large number of health risks, many of which could be fatal.

“More recently, there’s been a lot of research that’s really delved into the way that air pollution can really affect the body and body systems in other ways, including how air pollution can affect our neurological system, how it might be associated with outcomes such as dementia and Parkinson’s disease,” Berman said.