Officials are developing outreach and recruitment strategies for international students in hopes of offsetting the recent decline in international student enrollment during COVID-19 pandemic.

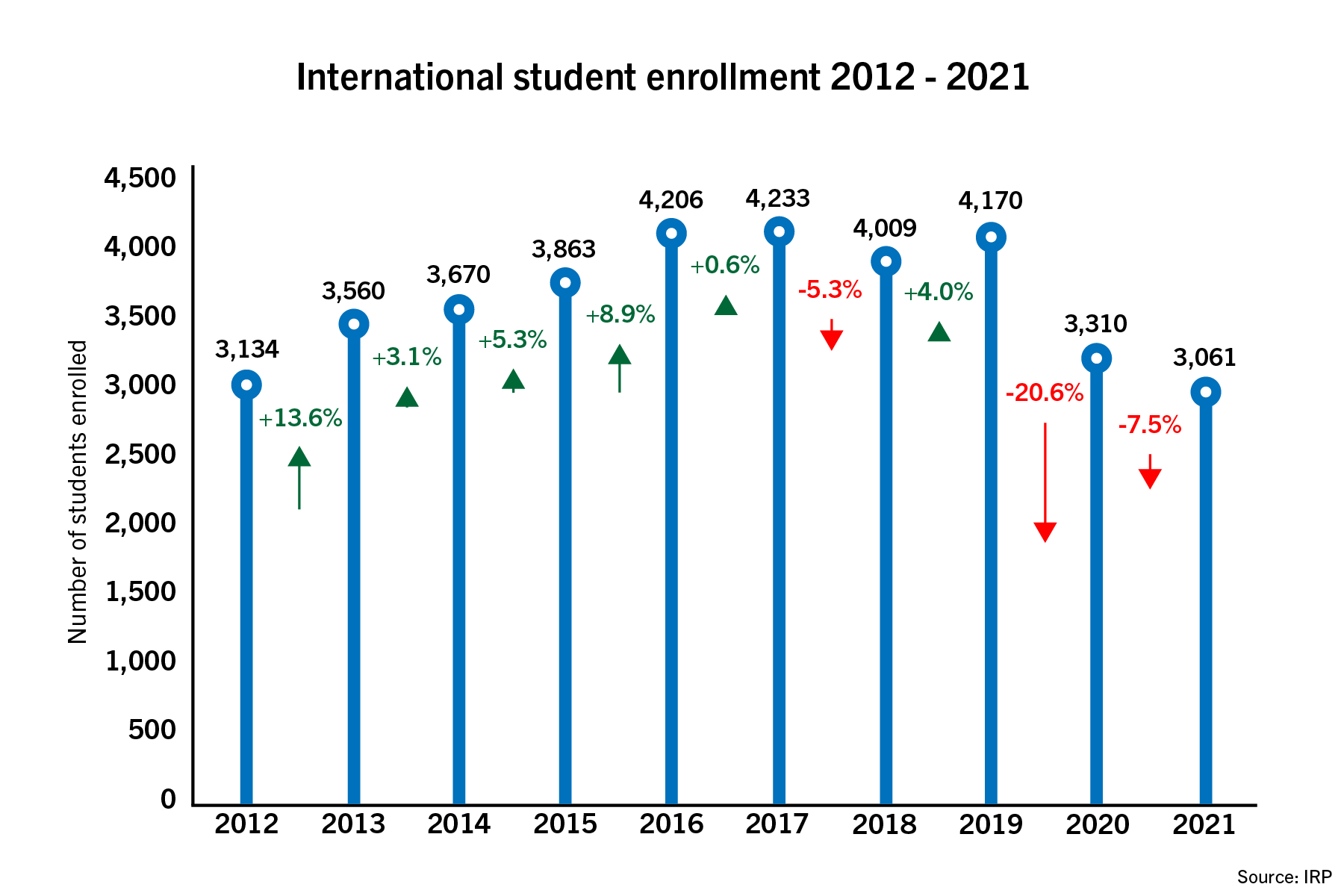

Jay Goff, the vice provost of student enrollment and student success, said at a Faculty Senate meeting last month that worldwide travel restrictions likely caused the 7.5 percent decline in international student enrollment this fall after nationwide totals dropped by 72 percent during the last academic year. He said GW’s enrollment management teams will rebuild international student enrollment levels with additional staffing and expanded communications to bring the student population back to campus.

“Planning for the rebuilding of our international student enrollments will be a priority for most of GW’s enrollment management teams,” Goff said in an email.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, numerous health organizations like the World Health Organization and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have required and recommended negative tests and vaccinations for international travel. For much of 2020, both the European Union and China heavily restricted travel to and from the United States.

Goff said the University created a set of “microtrend committees” that monitor changes in student markets to address the enrollment drop. He said officials are attending virtual college fairs and online forums to better connect with students from across the globe.

He said officials are also planning to hire more staff members to help plan international student recruitment efforts and visa support programs.

“The Enrollment and Student Success division will hire two additional positions this winter,” Goff said. “Both positions will focus on expanding new student outreach and support services that best fit the changing pandemic travel restrictions.”

Nicholas Anastacio | Graphics Editor

A University-wide task force that officials established earlier this year to assess what the GW community has learned from the pandemic found in its culminating report that University community members said the loss of international students this year was a “substantial challenge” to diversity, equity and inclusion on campus.

Experts in higher education said concentrated efforts to help international students, like aiding in smoother transitions to American study and raising funding for recruitment efforts, on behalf of American schools could help reverse the decline. They said University leaders should offer international students guidance on the process of applying for visas and moving to the U.S. to boost international student enrollment.

Alan Ruby, a senior fellow in the higher education division at the University of Pennsylvania, said international students need help applying for a visa – assistance that would help offset the decline of international students.

“Institutions who want to have significant international student enrollment need to have an infrastructure that can help students through that process,” Ruby said.

Ruby said a stronger support system for international students would remedy the enrollment drop and would ensure international students receive an enriching collegiate experience in the United States.

“If you want to be a welcoming place, you have to be able to offer that sort of service,” Ruby said. “And it’s an investment, but it’s also an obligation.”

Geraldo Blanco, an associate professor of higher education and the academic director of the Center for International Higher Education at Boston College, said the enrollment decline is the result of factors like delayed vaccine distribution efforts in other regions of the world, particularly East and Southeast Asia, and economic crises in those countries.

Blanco said international students also struggle with acquiring visas, which they must carry to enter the United States. He said the pandemic has created delays and backlogs during the process of obtaining a visa, given issues like local lockdown measures and quarantine regulations in hard-hit regions like China and India, making an already difficult process even harder.

“This already, in many cases, was a complicated and cumbersome process.” Blanco said. “And for the majority of last year, it was simply impossible to do that for many countries. And now, that’s caused so many delays and such a backlog that that’s a very significant, practical consideration.”

Blanco said because it’s “hard to know” when the pandemic will end, the decline in international enrollment is similarly difficult to predict. If the decline continues, he said he worries that prospective international students could decide to forgo American higher education indefinitely in the future.

“We’ve gone through a number of years without having to or without students being able to come to the United States to pursue their studies.” Blanco said. “So they may just altogether give up on the idea or postpone it indefinitely.”

Jeongeun Kim, an associate professor of higher and postsecondary education at Arizona State University, said the decline in international enrollment comes as a loss for all students. She said international students provide opportunities for domestic students to learn and experience different cultures and perspectives.

“I think it’s a lost opportunity for every student to learn from different people, learn about different cultures, different perspectives, different experiences.” Kim said.

Kim said justifying a virtual American education to international students who have to remain in their home countries given international travel restrictions has been a challenge for recruiters at American schools. She said since traveling and experiencing American culture is a key selling point for international students, schools must think of new ways to advertise to international students who cannot experience said benefits.

“It may be difficult for some of our institutions to justify why international students have to matriculate to the U.S. institutions when they cannot have those extra learning opportunities outside of the classes” Kim said.