The GW Police Department compiled a report breaking down the ethnic, racial and gender demographics of pedestrians that officers stopped in 2020.

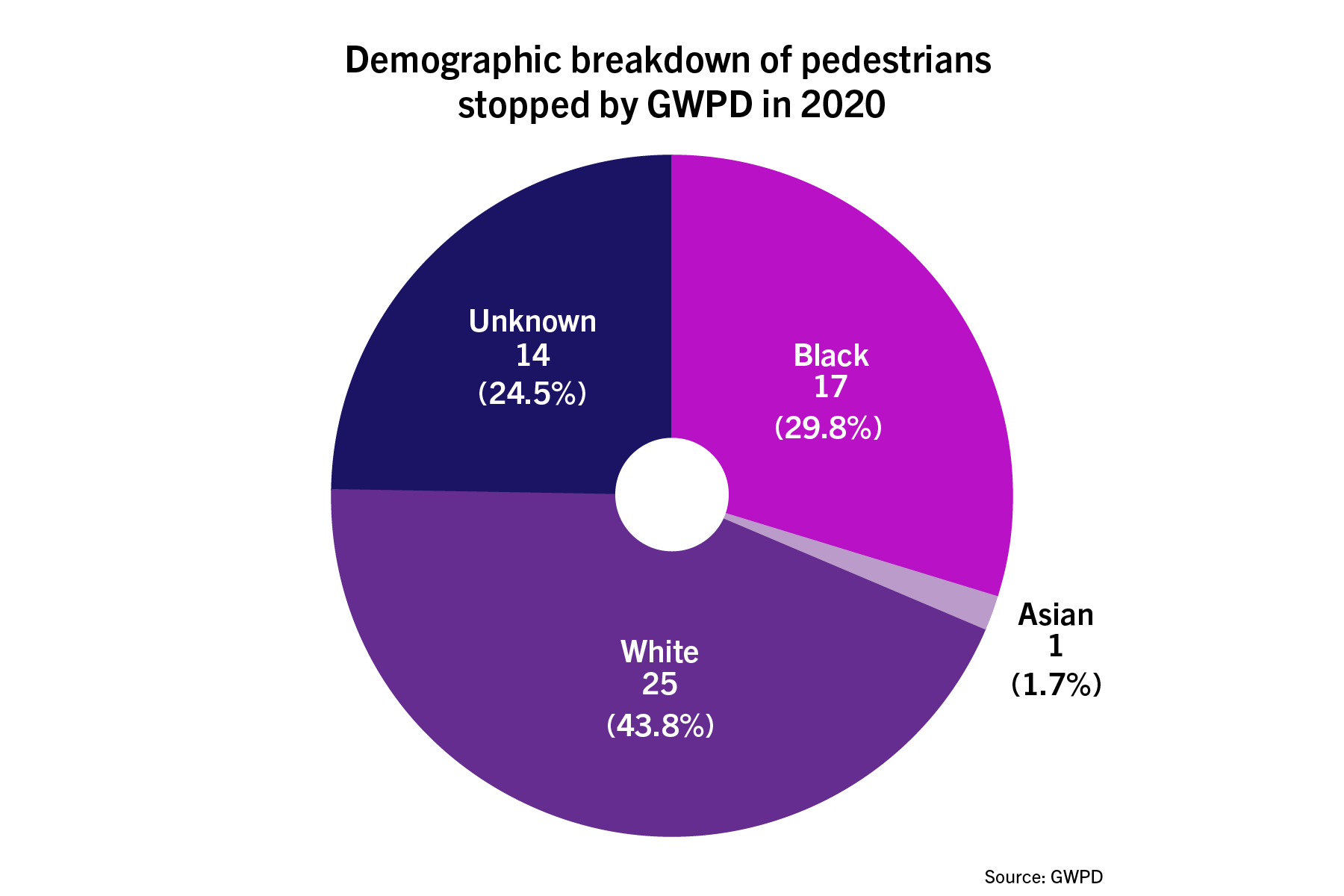

The report, which was provided to The Hatchet, states that GWPD officers stopped 57 pedestrians last year, of whom 25 were White, 17 were Black and one was Asian, while the races of the other 14 were unknown by officers. GWPD Chief James Tate said he commissioned the report to increase the department’s transparency with students and monitor interactions with the community more closely than in previous years.

“The reason we want to do this kind of report is to, first, show our commitment to transparency to our community,” Tate said. “But we also want our community to be reassured that GWPD does not target people for suspicion of crime based on their race, ethnicity or national origin.”

In the report’s ethnic breakdown, the data show officers stopped two Hispanic pedestrians and 23 non-Hispanic pedestrians, while the ethnicities of the other 23 were unknown. The report states that 26 of the pedestrians stopped were affiliated with GW, including 23 students, and 31 were not affiliated.

Protests against police killings of Black people have occurred nationwide in the past year following the murder of George Floyd and the killings of Breonna Taylor, Daunte Wright and nearly 1,000 others in the past year. Derek Chauvin, the former Minneapolis police officer who killed Floyd after he kneeled on him for about nine minutes, was convicted of second- and third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter last week.

“If I saw this report and the overwhelming majority of stops that we made were of people of color, I would be concerned,” Tate said. “Because that’s not the case based on this set of data, then I feel pretty good about what the department was in 2020 with regard to our stops.”

A total of 35 male pedestrians, 12 females and 10 additional people whose gender was unknown were stopped, according to the report.

Tate said demographics reports were mandatory at Rice University, where he previously served as chief of police until joining the department last year, and he wanted to release this data at GW to ensure the community understands the extent of the department’s interactions with the public.

He said GWPD generated the report with new software that can sort pedestrian stops by various demographic groups. Tate said demographic reports are not available for years prior to 2020 because GWPD did not use the software before his arrival to the department.

Nicholas Anastacio | Graphics Editor

The report states officers approached 57 pedestrians during 32 stops, which Tate said indicates that several stops can involve groups of multiple pedestrians. Tate said the three arrests that GWPD recorded during pedestrian stops last year involved cases of public urination, burglary and a previously barred subject entering campus.

Tate said all incidents listed in the report were officer-initiated as opposed to responses to 911 calls or other requests for assistance, most commonly initiated because of suspicious activity, like suspects trying to break open car doors.

Tate said the relationship between GWPD officers and students has improved since he assumed the role of chief last January, but he added that more work needs to be done to ensure that students feel comfortable with the department.

Tate said he plans to continue collecting and publicly releasing the demographic data every year, analyzing it to ensure there is no bias within GWPD.

“For a police department to be successful, you’ve got to have two things given to you by your community, and that’s trust and legitimacy,” Tate said. “We can’t confer those things on ourselves. It’s got to be given to us.”

Devon Bradley, the president of the Black Student Union, said the report did not show any clear examples of bias within GWPD and demonstrates that Tate is doing a “great job” reforming GWPD.

“When looking at the numbers, they really appear to be proportionate to the campus size and the projected number of people across our campus each day,” Bradley said.

The BSU published a letter calling for reforms to GWPD last June, like decreasing the number of officers present at events hosted by Black students, holding regular meetings with student leaders and improving cultural competency and sensitivity training. Since last summer, GWPD has implemented body-worn cameras and training reforms, heightened entry-level training requirements and released the department’s first-ever report of officer complaint data.

“One of the main things that I shared with Chief Tate was wanting to continue to compile data, such as the data that we have in front of us,” Bradley said. “I told him that I thought that that would be a great way to continue to increase the positive aspects within the relationship between students and GWPD.”

Bradley said the release of the report also marks a step toward further reform, but more work remains to be done.

“Obviously, GWPD has not reached perfection or even its target rate of what they’re going to view as being completely reformed and efficient,” he said.

John Sloan III, a professor of criminal justice at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, said the data in the report is not enough to clear GWPD from any potential bias. He said a wider pool of data, like a larger sample size of stops and information about their background, is necessary to determine the intent of officers.

“There’s no way that you can make any kind of interpretation about the intent of the officers from these kinds of data,” Sloan said. “You would need to know a lot more, like the race of the officer that was involved in the stop.”

He said most university police departments do not release demographic information like the data found in the report, oftentimes because of fear of bias-related accusations that could spark backlash from the local community.

“Part of the reason for not releasing this kind of stuff is because people will misunderstand or misconstrue or misinterpret and so then they get in hot water, maybe unnecessarily,” Sloan said. “So the simplest way of handling this is to not release it.”

He said that although the report doesn’t have enough data to make clear conclusions right now, Tate made the right decision because its release will help increase the department’s transparency.

“On the positive side, it’s a starting point, and transparency is always better than opacity,” Sloan said.

Jared Gans and Jarrod Wardwell contributed reporting.