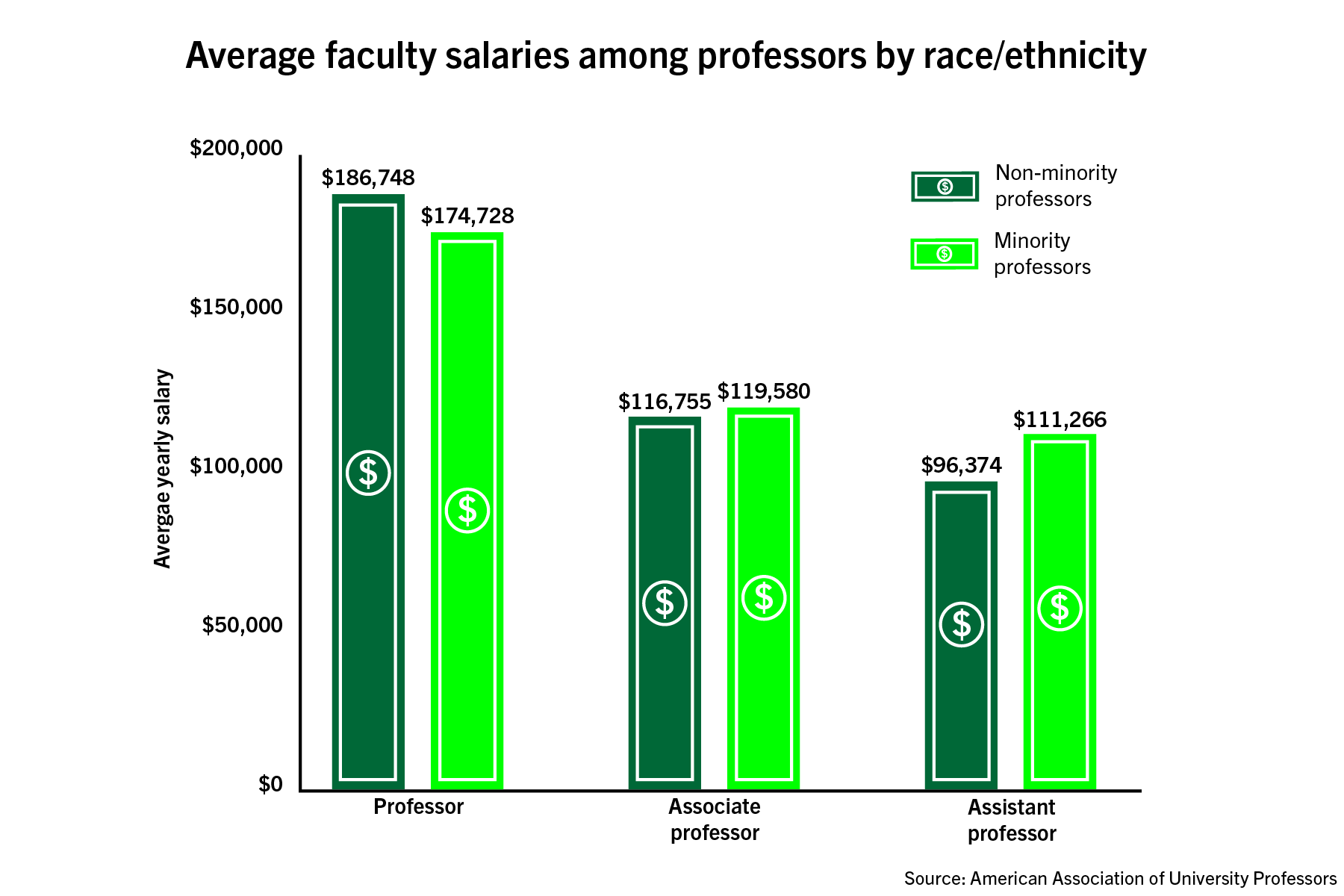

Full professors of color from across the University earned a lower salary than their non-minority counterparts this past academic year, while minority faculty salaries for associate and assistant professors were higher, University data shows.

About 84 full professors of color earned an average of $12,020 less than 285 non-minority professors, but minority associate and assistant professors made more than their non-minority counterparts, according to University salary data. Experts in economics said several factors can affect disparities between minority and non-minority faculty, like supply and demand of the job market and increased hirings that drive wage growth.

The faculty salary data is broken down by minority and non-minority professors across three levels of professorship – full, associate and assistant – and includes an aggregate of total average pay across GW’s eight schools.

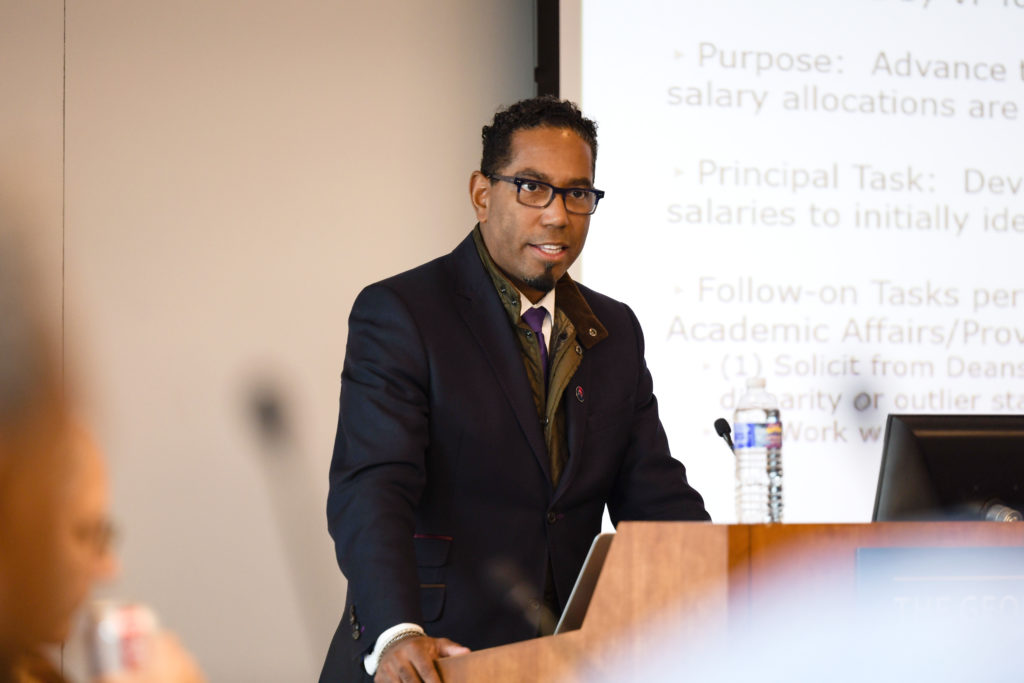

Chris Bracey, the vice provost for faculty affairs, and Cheryl Beil, the associate provost of academic planning and assessment, said the aggregate data across the three faculty ranks doesn’t reveal “any meaningful conclusions” because the average salary for full professors is far higher than associate or assistant professors.

“A faculty member’s salary is influenced by many factors including but not limited to rank, time in rank, department or discipline, tenure status, circumstances of hire (i.e. recruited as lateral hire) and retention agreement terms,” they said in an email.

Nicholas Anastacio | Graphics Editor

The data shows that 96 associate minority professors were paid an average salary of $2,825 more than 259 non-minority faculty, and 74 minority assistant professors earned nearly $15,000 more than the other 144 faculty.

Full professors in GW Law earned the most on average at $275,860 while full professors in the Columbian College of Arts and Sciences made the least at less than $150,000, according to the data. Associate and assistant professors in the School of Business were paid the most on average at $174,870 and $184,675, respectively, while associate and assistant professors in CCAS earned the least on average at $103,668 and $89,129, respectively.

GW currently employs fewer minority professors among all three levels, with minority faculty making up about 22.7 percent of full professors, 27 percent of associate professors and 34 percent of assistant professors, according to the data.

Bracey and Beil said officials excluded some schools’ information to preserve anonymity because faculty salaries could be easily calculated and their identities revealed if included in the data. Only three schools – CCAS, GWSB and the School of Engineering and Applied Science – were listed in officials’ data for each of the three ranks because they had more than five minority and non-minority faculty members at each level.

Full professor data excluded faculty from the Elliott School of International Affairs and the Graduate School of Education and Human Development, while associate professor data excluded GW Law faculty. Assistant professor data excluded faculty from the Elliott School, GSEHD, the law school and the Milken Institute School of Public Health.

Officials only included the racial breakdown of the School of Nursing’s faculty salary in the aggregate data because the school had six minority faculty in total.

Full minority professors in the law school and the public health school earned more on average than their full non-minority counterparts, according to officials’ data. Minority associate professors at the Elliott School and assistant professors in CCAS and GWSB earned more on average than their non-minority counterparts.

The data shows that non-minority full professors in GWSB, CCAS and SEAS earned a higher average salary than their minority counterparts. Non-minority associate faculty in GWSB, CCAS, SEAS, GSEHD and the public health school earned more on average, with the same for non-minority assistant professors in GWSB.

Economic experts said factors like competition in the job market and length of tenure at an institution can drive disparities among minority and non-minority faculty salaries, especially at a research institution like GW.

Bruce Weinberg, a professor of economics at The Ohio State University, said full minority professors, who are typically employed longer than minority associate and assistant professors, might receive lower salaries because wage disparity issues could have been unresolved when they were hired.

“They are from older cohorts who may have been treated differently and any disparities in raises may have compounded for them for quite some time,” he said.

Weinberg said many schools likely had little, if any, rises in pay this past year due to the COVID-19 pandemic and its effect on the economy. He said he is unaware of whether or not this lack of change has had an impact on minority faculty, but evidence suggests that female faculty careers were “held back” due to the pandemic, which may disadvantage them in terms of future compensation.

Michael Rizzo, a professor of economics at the University of Rochester, said factors like discipline type, outside offers and supply and demand of the higher education labor market can affect faculty salaries. He said the disparities between minority and non-minority faculty salaries at GW don’t necessarily equate to discrimination because the GW data is not explicit in its breakdown of salary packages and other information, like funding for labs.

“I know of some professors who take a little bit lower salary in exchange for a long term contract,” he said. “I know some people who would take a little bit lower salary in exchange for funding like larger book budgets and research budgets.”

GW faculty circulated a petition earlier this year calling on University officials to enact a “cluster hire” of underrepresented faculty. The petition has since gathered more than a thousand signatures.

Tim Diette, a professor of economics at Washington and Lee University, said wages for minority faculty have risen in recent years with heightened demand for professors of color given the diversity of knowledge and experience they bring to campuses. He said universities have begun to prioritize recruiting professors in underrepresented groups like the Black and Latino communities as a result.

Diette said universities have recently started conducting internal diversity audits to understand these disparities, improve their faculty composition and enhance research, student representation and mentorship opportunities.

Officials announced plans to conduct the first-ever University-wide diversity audit in January but have yet to select a third-party organization.

“Given the impact of race on the lived experience of individuals, having a diverse workforce, a diverse faculty will bring the richest conversations to every campus,” he said.

Carly Neilson contributed reporting.