Female full professors in the School of Business are continuing to make slightly more money than their male counterparts this academic year.

Female full business professors are making 14 cents more for every dollar that their male counterparts make, according to data presented at this month’s Faculty Senate meeting. Experts in higher education said the disproportionate number of female faculty in the business school may distort that data, which indicate that female full and associate business professors make more money than male business professors.

Sidney Lee | Graphics Editor

“Gender inequity is an important issue in academia as well as in the business world,” business school Dean Anuj Mehrotra said in an email. “Hence it is of great concern to me as a dean. During my time at GWSB, I have endeavored to resolve these concerns by taking a systematic, market-based approach to faculty salary negotiations and have conducted salary equity reviews in collaboration with the Office of the Provost.”

Mehrotra said faculty salary varies by department. He said there is a gender disparity in salaries because of “where these faculty are located.”

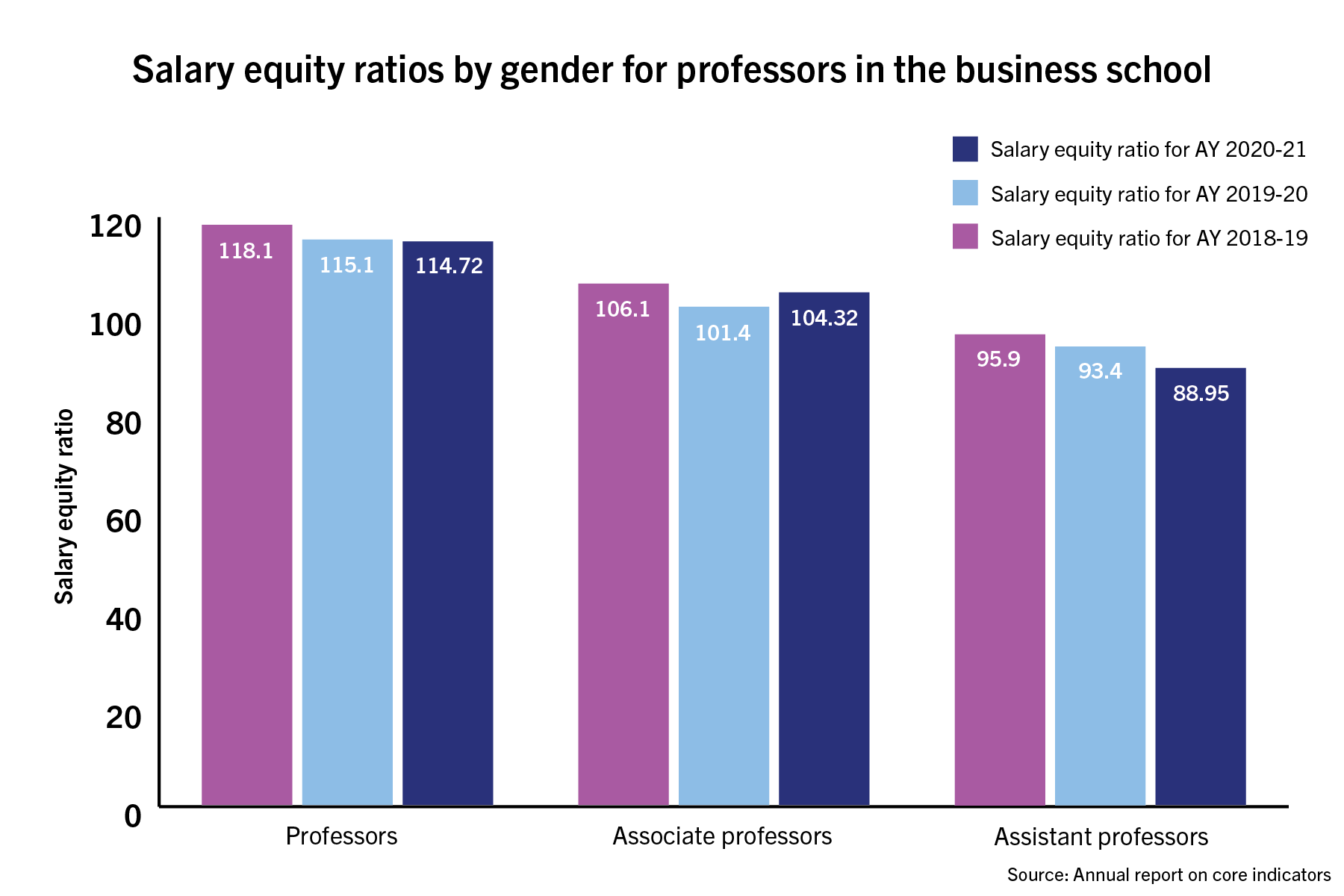

Salary equity in the business school has decreased slightly for faculty over the past three years.

Female business professors made 18 cents more for every dollar that their male counterparts made in the 2018-2019 academic year, according to the core indicators report from last March. The number decreased to 15 cents more in the 2019-20 academic year and is now at 14 cents more for the current academic year.

Mehrotra said the decline in salaries is “primarily” driven by changes in personnel. He declined to say how faculty members have responded to the changes in salary equity in recent years.

Mehrotra said the equity ratio for assistant professors in the business school stands at 88.95 this academic year, indicating that for every dollar that male professors make, female professors make roughly 12 cents less. He said the difference could be due to male assistant professors often working in “higher-paying disciplines.”

“In addition, the Office of the Provost conducts an annual equity review of faculty salaries, including GWSB faculty salaries, and recommends equity adjustments be made when warranted,” he said.

Tom Barkley, a professor of finance practice at Syracuse University and the chair of the budget and fiscal affairs committee at Syracuse’s University Senate, said given the slowly declining equity ratio in the business school in the past three years, the difference in salaries could be the result of a few female professors whose salaries are “disproportionately high,” distorting the overall ratio.

“Let’s say as other male salaries come up, then the ratios are going to decrease and tend to get closer to 100,” he said. “But without seeing the actual data and being able to play with it, it sounds to me that there is a female professor who gets a really good salary and that has thrown the ratios a little bit out of whack.”

There are 11 female full professors and 26 male full professors in the business school this year, according to the core indicators report. These numbers have remained largely the same with only slight fluctuations since the 2018-19 academic year, when there were 10 female professors and 29 male professors in the school.

Tyler Bickford, the chair of the university senate budget policies committee at the University of Pittsburgh, said that because the number of professors in the business school is “too small,” a few highly paid female professors may bring up the average. He said business schools don’t generally pay female full professors more than their male counterparts.

“There are some well-paid women full professors within the business school, but I don’t think that’s the expression of some broader trend or generalization about how full professor pay works in North America,” Bickford said.

He said in most higher education institutions, women are more likely to be overrepresented in lower ranks like non-tenured track positions, especially in schools or fields that often have lower pay.

Female professors make up 29.7 percent of all full business professors this year, 33.3 percent of all associate professors and 36.8 percent of all assistant professors, according to this year’s core indicators report.

Charles Chang, the chair of the equity and inclusion committee in Boston University’s Faculty Council, said if the University is willing to acknowledge and actively work toward decreasing the salary disparity between female and male professors, then female faculty members would have an “advantageous” position to bargain for higher salaries and more resources.

“As the business school faculty better approximates a 1 to 1, male-to-female faculty ratio, then there’s less of a disparity in terms of the drive to retain faculty of a particular gender,” he said.

He said if female full professors remain underrepresented in the school, officials could be pressured to tend to negotiations with potential new hires to maintain retention while increasing those professors’ salary rates.

“The loss of a male faculty member from the business school doesn’t hurt as much as the loss of a female faculty member from the business school because the loss of a male faculty member doesn’t increase the gender disparity,” Chang said.