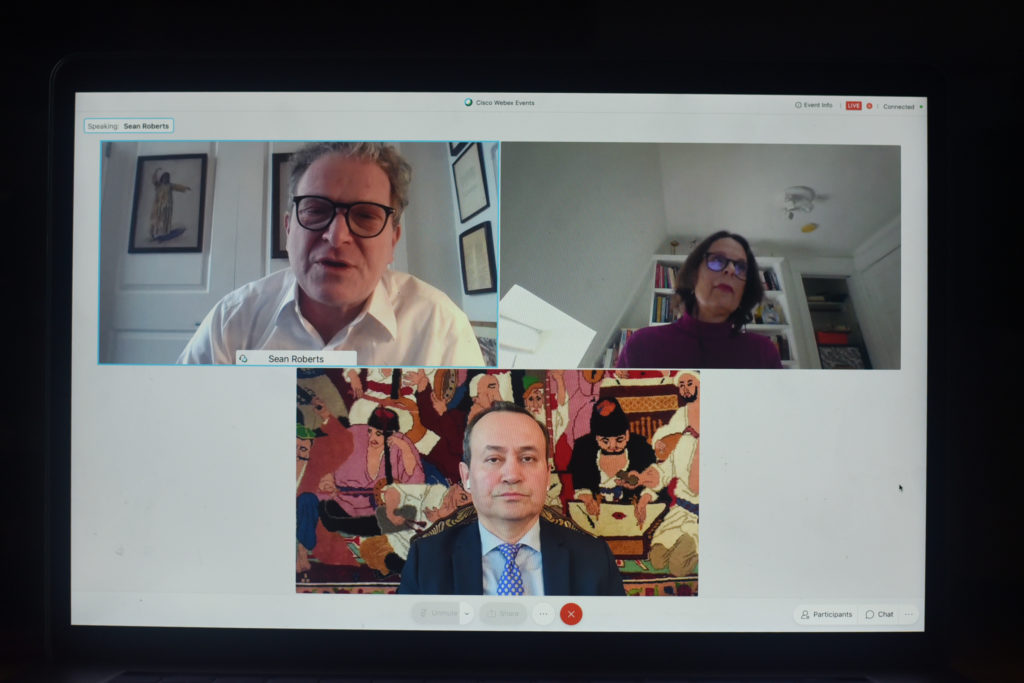

Human rights experts discussed the detention experiences of ethnic Uyghur minorities in China’s Xinjiang region Tuesday.

The Elliott School of International Affairs hosted the event, which featured a discussion about nonprofit news organization Radio Free Asia’s newly published report detailing firsthand accounts of Uyghur harassment and internment. Sean Roberts, an associate professor of the practice of international affairs, moderated the discussion, which was held in collaboration with the school’s Central Asia Program.

Since 2016, more than a million Uyghur and other Muslim minorities have been detained and imprisoned in China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region as part of a Chinese counter-terrorism campaign, according to a 2019 U.S. State Department report on global human rights practices.

Betsy Henderson, the chief strategy officer of Radio Free Asia, said the organization’s research department recently carried out a series of in-depth interviews with eight survivors with direct experience inside detention facilities, providing a clearer portrait of Chinese repression and documentary evidence of human rights violations.

Henderson said the research project employed a “non-traditional” interview approach to ensure the comfort of its Uyghur participants.

“We realized that these were people who had experienced very traumatic things, and we did not want to ‘re-traumatize’ them by an extensive formalized interview,” she said. “The interviewer allowed these stories to flow rather organically and allowed people to frame their stories as they saw them, which was a very long process.”

Henderson said while the interviews only included eight survivors and cannot be considered representative of the entire Uyghur experience, the research project still provides an “informed window” into current life in Xinjiang.

“The intimacy of detention cruelty gives these detainees unique insight into Chinese repression in Xinjiang, and the human beings who are sustaining it, where considerable suffering is also taking place in non-camp detention settings,” she said.

Roberts, the moderator, said while a “perfect storm” of various factors led the Chinese government to persecute its Uyghur minority, the post-9/11 global “war on terror” encouraged party officials to perceive Uyghur cultural and religious practices as being associated with international terrorism.

“What I found in my research was that there wasn’t really a terrorist threat in the Uyghur region when this began in 2002,” he said. “But after over a decade of repression, we found there was more violent resistance happening, and a couple of violent attacks occurred that looked like terrorist attacks, which led to a cycle of oppression and resistance. At some point the Chinese government decided they were done with that and decided to just completely break these people.”

Maya Wang, a senior China researcher at Human Rights Watch, said historical examples of minority repression “don’t quite apply” to the Uyghur experience since technological advancements like facial recognition technology and ID scanners have allowed state authorities to surveil and restrict movement in ways that current international human rights laws don’t address.

“Historically you have plenty of regimes that commit genocide and subjugation against minority populations everywhere,” she said. “But what is happening in Xinjiang is that the use of technology has enabled the state to have a very intrusive kind of control over people’s body and soul in a way in which is not captured by existing legal definitions of genocide or crimes against humanity.”

Wang said the United States can help alleviate the Uyghur crisis by imposing stricter financial sanctions on U.S. surveillance companies who work with the Chinese government.

“The types of sanctions which target the financial transactions of these companies are needed,” she said. “What we are seeing is that if some of these companies are able to help the Chinese government surveil the Chinese people, in 10 years time, people in China will be unable to resist any kind of oppression, a trend we are already seeing.”

Alim Seytoff, the director of Radio Free Asia’s Uyghur Service, said Muslim majority countries have notably refrained from responding forcefully to the Uyghur situation out of fear of ruining future economic partnerships with the Chinese government – like the Belt Road Initiative, a major Chinese-led infrastructure project stretching from East Asia to Europe.

“Saudi Arabia and other Muslim majority countries are great beneficiaries of Chinese investment, so they don’t want to bad mouth China in any way,” he said.