For the first time ever, the GW Police Department publicly released three years of police complaint data last month, revealing a regression of citizen complaints and internal investigations that student leaders and officials said could continue to fall in the years to come.

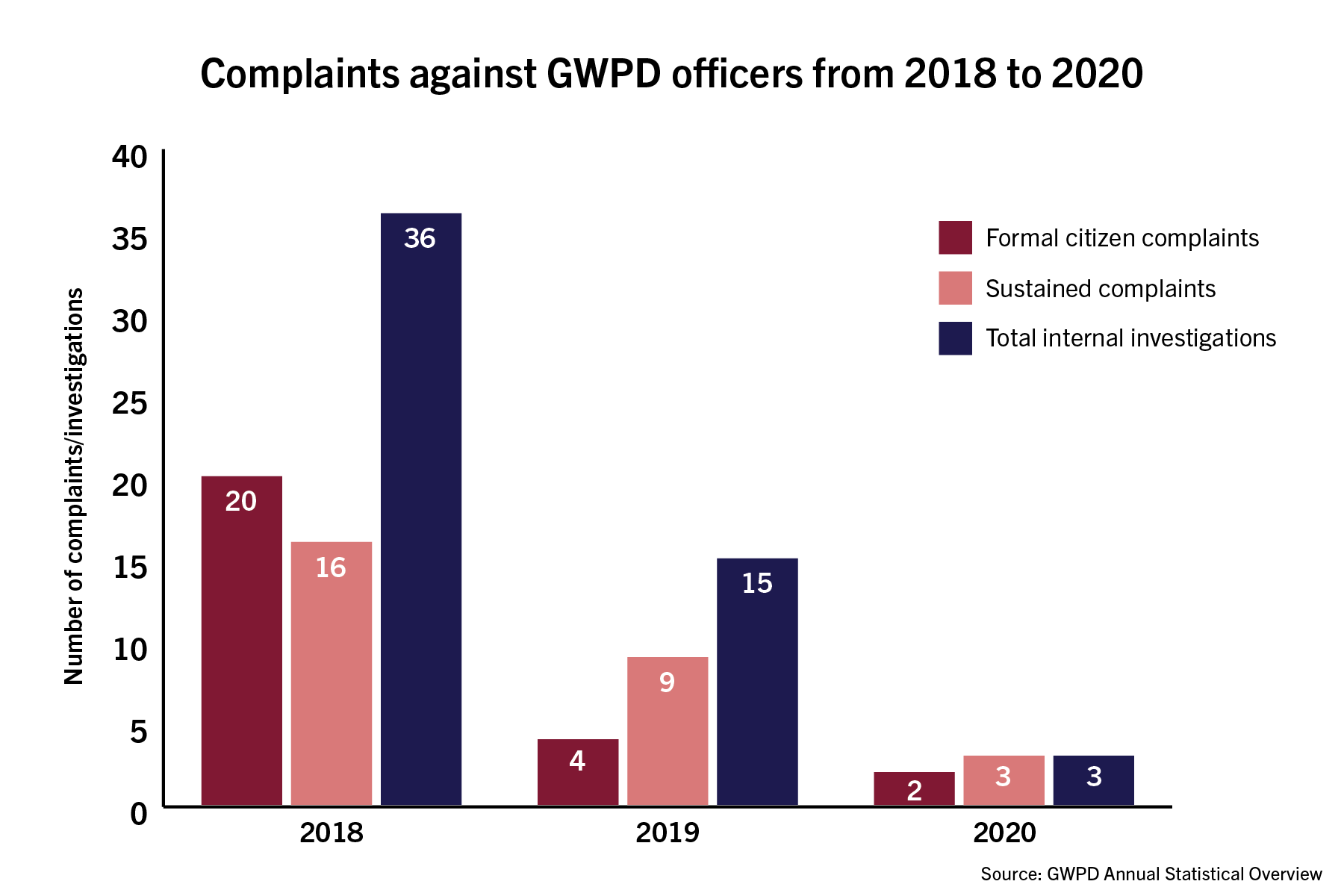

The number of complaints and violations dropped by more than 80 percent since reaching “very high” levels in 2018, with 20 complaints falling to just two in 2020, according to the report – which documents three years of internal investigations, civilian complaints, officer violations, calls for service and arrests. Following a year highlighted by police brutality and calls for reform, GW community members said the release marks a breakthrough in enhancing transparency and mending campus police relations.

Sidney Lee | Graphics Editor

The findings show nearly every category at its highest in 2018, which yielded an above-average number of complaints, GWPD Chief James Tate said. Tate counted 20 complaints filed by citizens, 16 officer violations and 36 investigations in 2018.

“Those numbers are very high for a police department this size,” Tate said. “Typically you do not see that number of complaints being investigated in a police department that’s less than 100 people. Those numbers are very high.”

The complaint levels in 2018 came as GWPD faced rapid turnover when its chief resigned.

Tate attributes part of 2018’s totals to a miscalculation of investigations, half of which he estimates are related to human resources matters including management or personnel issues, like coming into work late. He said the investigations were evenly split between complaints from students, faculty, staff and GWPD employees.

Since 2018, the annual figures have dropped off, the data show. In 2019, department violations shrunk to nine incidents, and investigations and civilian complaints were cut in half. In 2020, the data reports just two civilian complaints, three investigations and three violations.

Tate said officer violations, listed as “sustained complaints” in the data, often lead to written or verbal counseling before suspension or termination.

He said an officer was terminated last year following a patrol vehicle crash involving “a significant amount of damage” but no injuries. The two other investigations in 2020 involved an officer being placed on administrative leave after appearing to push a student down a flight of stairs and a community member complaining that an officer didn’t handle an issue with enough “care and concern,” which led to “corrective and disciplinary action,” Tate said.

The report comes as Tate has prioritized restoring community relations and building trust with students after joining GWPD last year. He has implemented body-worn cameras and training reforms, heightened training hours and scheduled the department’s first-ever racial-profiling report for March.

Tate participated in community discussions this summer, pledging to enhance “woefully inadequate” officer training.

“Leadership starts at the top, and I have to model that behavior that I expect our officers to model,” Tate said. “And then, of course, I expect that type of behavior and interaction with the community to permeate all the way through our department.”

Devon Bradley, the president of the Black Student Union, said he was “very pleased” to see complaints regress over the years and read the data after Tate shared it with BSU and the Student Association last month. Bradley noted the data’s release as “progress” for the future and said he wasn’t surprised by the regression given Tate’s “dedication to transparency and our safety.”

“It may not be perfect right now, but I know that Chief Tate, GWPD and GW can get there,” he said.

Bradley said Tate has involved him and other BSU members in discussions about how the department can continue to unify students with police, inviting Bradley to serve on a hiring panel for a GWPD commander in July. He said Tate’s relationship with BSU improves upon a “lack of leadership” and a “lackluster culture” within the department before 2018, when such opportunities weren’t available.

“I’m happy that Chief Tate keeps us updated and at the table,” he said. “I can’t emphasize how imperative that is and how it prevents some of the issues between students and police officers on our campus.”

Bradley said Black students on campus have faced these departmental issues in the past, often when GWPD officers would stop Black students on campus and ask for ID. Bradley said he and many other Black students have come to terms with the encounters that he describes as a “microaggression,” and he isn’t aware of students filing any related complaints.

He said GWPD should continue releasing the complaint data in future years so officers can continue to build trust with students. Bradley said officials he’s spoken with have been open to the idea of releasing a more “comprehensive” report that details who was arrested and any related safety concerns regarding violent crime.

“Students are going to trust their leaders,” he said. “They’re going to trust Chief Tate, and this officer and that officer, and that’s really what they’re supposed to be seen as – authority figures. But if the trust isn’t there, they can’t do their job.”

Senior Kent Trespalacios – a member of the Division of Safety and Facilities’ Student Advisory Board, which launched in 2018 to improve student relations with GWPD officers – said he was “taken aback” after reviewing the data’s 2018 figures, noting more complaints than he would guess given the department’s size of fewer than 100 officers. He said the 2019 totals seemed closer to what he would expect from GWPD.

“I was surprised that it was at that level because from my understanding, before seeing these numbers, if I were asked, I would suspect that the number of complaints would be very low considering the size of the police department,” he said.

Trespalacios attributed the low count in 2020 to a relatively empty campus during the COVID-19 pandemic and the training reforms Tate implemented, and he expects the totals to stay low in the years ahead.

“Seeing the raw numbers will help dispel some of that view of misconduct and then also improve transparency that in 2020, there were three total internal investigations and so on, so I think it’s very important,” he said.