I received an email from the Pre-Law Student Association earlier this month announcing that officials had terminated the University’s only pre-law adviser position. That person was crucial to working toward any law school acceptance.

The pre-law adviser was responsible for reviewing students’ law school applications, organizing law school fairs, hosting informational sessions, helping students navigate law school financing and advising GW Mock Trial. Removing her position directly comes at the expense of students interested in pursuing a career in law, who now have no GW resource to help them navigate their application process.

But the layoff didn’t happen in a vacuum. While her immediate removal can be traced to the financial implications of the pandemic, the terminated position represents a symptom of a long and dysfunctional trend in higher education – one characterized by administrative bloat and the increasingly blurred lines between economic markets and higher education.

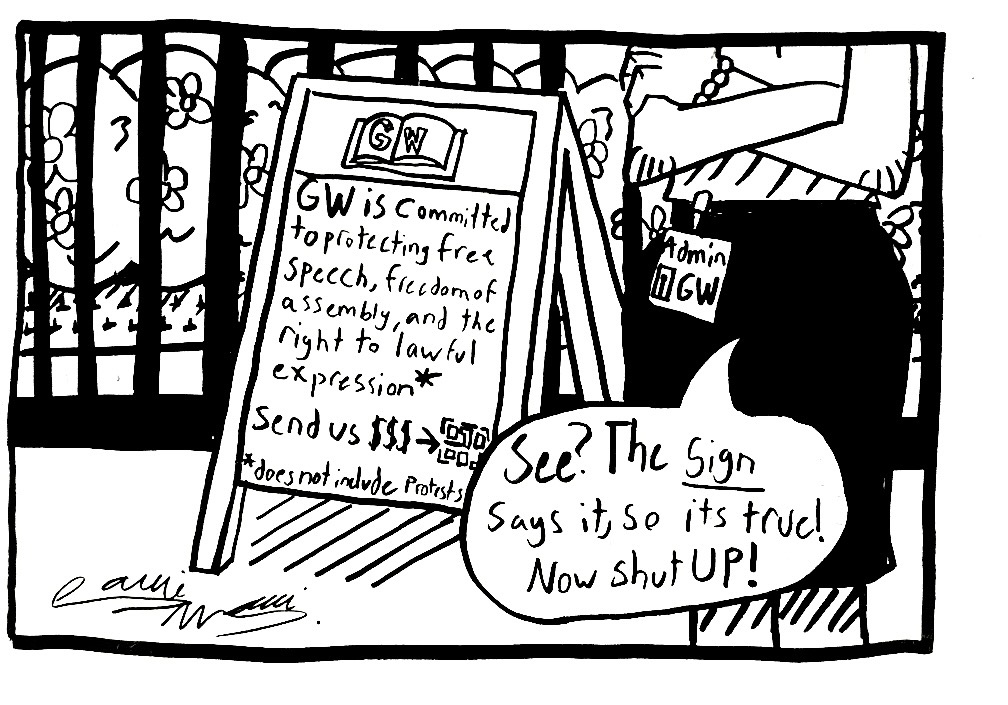

As students and faculty alike have suggested, not only should University President Thomas LeBlanc resign just as a means of recognizing his complete indifference to and abandonment of GW’s academic values, but administrators should also work toward reorganizing their priorities and restructuring themselves. Officials must give financial decision-making power to faculty, reinstate faculty autonomy of administrative decision making and prioritize job security.

The structure of the modern university can be traced back to World War II. While the Depression had left higher education institutions in desperate financial need, the war marked a drastic change in the structure of higher education as the government invested more than $300 million for war-related projects. Following the war, large increases in student enrollment and government-funded research contributed to the growth, power and size of university bureaucracies. The primary mission of these bureaucracies was to mobilize university resources to serve the interests of their funding sources: business and the armed forces.

By the 1980s, teaching and research itself had been reformed to accommodate the needs of the private sector and remain competitive with other universities. Knowledge became much more valuable because it was able to be bought and sold and traded in global markets. Universities have also responded to the pressure to be profitable through market activities, like becoming intricately involved in finance and real-estate development. GW reflects this perfectly, having owned more than $428 million in taxable property while investing more than $1.03 billion in 2019 alone.

This transformation in higher education has cultivated novel forms of knowledge that help academics, the government and private businesses make more money. Unfortunately, this transformation undermined academic institutions’ capacity to generate positive knowledge, much less critical thought.

As universities changed, faculty autonomy and governance became increasingly restricted. The primary goal of administrative institutions shifted to pursue new sources of revenue, while shared governance and faculty opposition stand counter to that goal. This being the case, universities hired individuals that are more directly responsible for revenue generation, like those in administrative roles.

These revenue goals often justified the hiring of faculty not protected by tenure, who are less likely to outwardly oppose unjust administrative decisions because of their job insecurity. It is estimated that adjunct or untenured faculty make up to 75 percent of instructors. In contrast, universities dramatically expanded the number of administrators while boosting administrative salaries, especially those of university presidents, like Thomas LeBlanc who makes roughly $800 thousand or GW administrator Shahram Sarkani, who made about $1 million in 2016.

The growth of administrative bloat accompanies the process of “academic prioritization” that aims to convert low revenue-generating disciplines, like social sciences and humanities, into market-oriented disciplines, like STEM. When budget cuts need to be made, non-tenured faculty, social studies and humanities departments are the first to go because such cuts are essential in redirecting revenue toward majors and services that have potential for market growth.

It’s this grossly inequitable trend of higher education, one that favors inflated administrative salaries, useless bureaucratic positions and bending to the will of the market, that has led to the pre-law adviser’s termination. And it’s not just the adviser, of course. More than 70 workers have been laid off since this summer, and the number will only continue to rise amid flawed administrative decisions in an already structurally unsound higher education system.

The University needs to reinstate the position of the pre-law adviser, but they can’t stop there. They have to work toward fixing the root cause of why she was let go – and while blaming finances is the easy way out, it ignores a long, complicated history of structural mismanagement and undermining of traditional academic prioritization.

Karina Ochoa Berkley, a sophomore majoring in political science and philosophy, is an opinions writer.