The GW Police Department adopted a series of reforms late last month that officials hope will start answering student leaders’ demands for more effective policing.

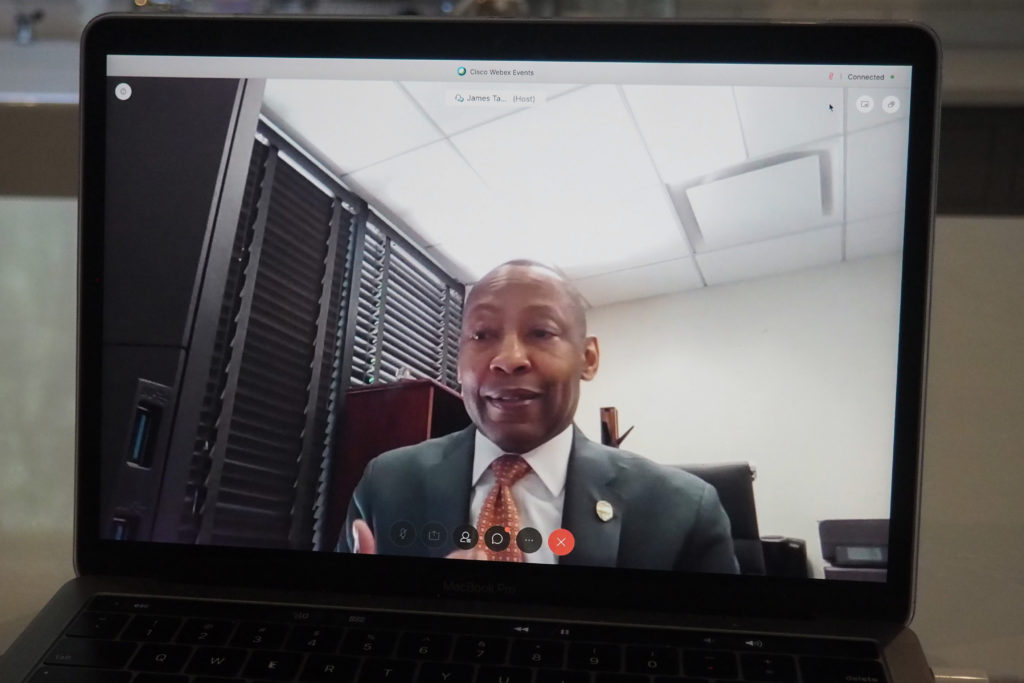

GWPD Chief James Tate organized two 40-hour, weeklong training sessions during the first two weeks of August with 18 focus points that included defense tactics, unconscious bias training and de-escalation skills, University spokesperson Crystal Nosal said. Tate said the revamped training program, new body-worn cameras and an increased focus on community involvement highlight the department’s latest efforts to improve campus policing.

“If the GW community doesn’t trust its own police department, then we have to find ways to fix that,” he said. “We can never be effective if we don’t have the University’s or the community’s trust.”

Tate said the changes are the first step in addressing concerns about a discord between officers and students. The Black Student Union wrote a letter to GWPD in June, demanding the department work to improve its relationship with students.

Tate said GWPD’s new reforms include greater community involvement in the officer hiring process, during which students from the Student Association and student organizations for “underrepresented” communities will be able to ask interview questions and exchange perspectives with the department.

“They are so valuable to us or to me as an administrator because students see things that I can’t see or I don’t see,” he said. “They pick up on things that I don’t pick up on.”

Tate said he plans to hire a “community outreach officer” in the next month to build relationships with students and enhance community policing. He said officers will arrange video calls to engage students in any discussions with the department.

Division between students and GWPD grew earlier this year when an officer pushed a student down several stairs outside University President Thomas LeBlanc’s on-campus residence during a protest. That officer was placed on administrative leave, and officials announced the department’s new reforms in March following an internal investigation into the incident.

The February encounter between the officer and student compelled officers to use body-worn cameras to boost accountability and transparency within the department, Tate said. He said releasing video footage provided by the cameras places the department in better communication with the community.

“When we capture a good piece of video, that can help all of our officers get better, but it also helps with accountability, with transparency when the public knows that we have the video, and then we’re willing to share it,” Tate said. “Anytime we do that, I think it strengthens our relationship with the community.”

Public access to body-worn camera footage has become a topic of debate throughout the District, as the D.C. Council repealed emergency police reform legislation in July, returning the deadline for the Metropolitan Police Department to release arrest footage from three days to five days.

Following last week’s fatal police shooting of 18-year-old Deon Kay in Southeast D.C., MPD released footage within 24 hours of the incident, which shows Officer Alexander Alvarez shooting Kay in the chest when Kay appeared to pull a gun out of his pocket and throw it into a nearby yard. Protesters who gathered outside the Seventh District police station Wednesday said the shooting was another case of police brutality.

Jeffrey Kerch, a GWPD officer who completed the department’s training last month, said he spent between eight to 12 hours learning how to wear and operate body-worn cameras. He said he doesn’t think the training will change how he acts on duty, but the cameras will uphold transparency within the department.

“There’s a lot of calls for transparency within police departments in general, and I think body-worn cameras can help with that because we activate them when we’re interacting with the public and during incidents,” Kerch said. “And it’s a camera. It doesn’t lie.”

Despite the recent training improvements, police and policy experts said the department needs to focus on reworking entry-level training requirements and swiftly releasing body-camera footage to ensure department-level reform pays off.

Frederick Shenkman, a professor of criminology and law at the University of Florida, said the high number of training directives taught within the 40-hour training period won’t help officers in real-life situations because of the lack of time officers could spend on each topic. He said officers must complete a college education and police training that lasts more than a few months to be fit for service.

“Police want to consider themselves professionals, but obviously, there’s no other profession that you could think of that has four-months training,” Shenkman said.

Tate, the GWPD chief, said although his officers only trained for one week, training will be “continuous” throughout the year, following the formation of the department’s new training unit led by a lieutenant and an officer. Shenkman said the plan “sounds sort of nice” but doesn’t solve the main problem of providing sufficient entry-level training.

“I think we’re past due time that any job that has high-level professional responsibilities needs to have a commensurate amount of formal education, in addition to the training,” he said.

David Hooker, a professor of conflict transformation and peacebuilding at the University of Notre Dame, said body-worn cameras could be a helpful mechanism to determine whether officers need more training, hold officers accountable and demonstrate to community members how officers respond to crime.

But he added that footage from body-worn cameras needs to be released in full, consistently and around the time the incident occurred to show the community that officers have not nit-picked which clips to reveal.

“Otherwise, community suspicions of officers covering for one another gets reinforced, and it’s almost too little, too late,” Hooker said.

Sarah Roach contributed reporting.