Researchers in the School of Engineering and Applied Science and the Milken Institute School of Public Health are developing an at-home test for COVID-19.

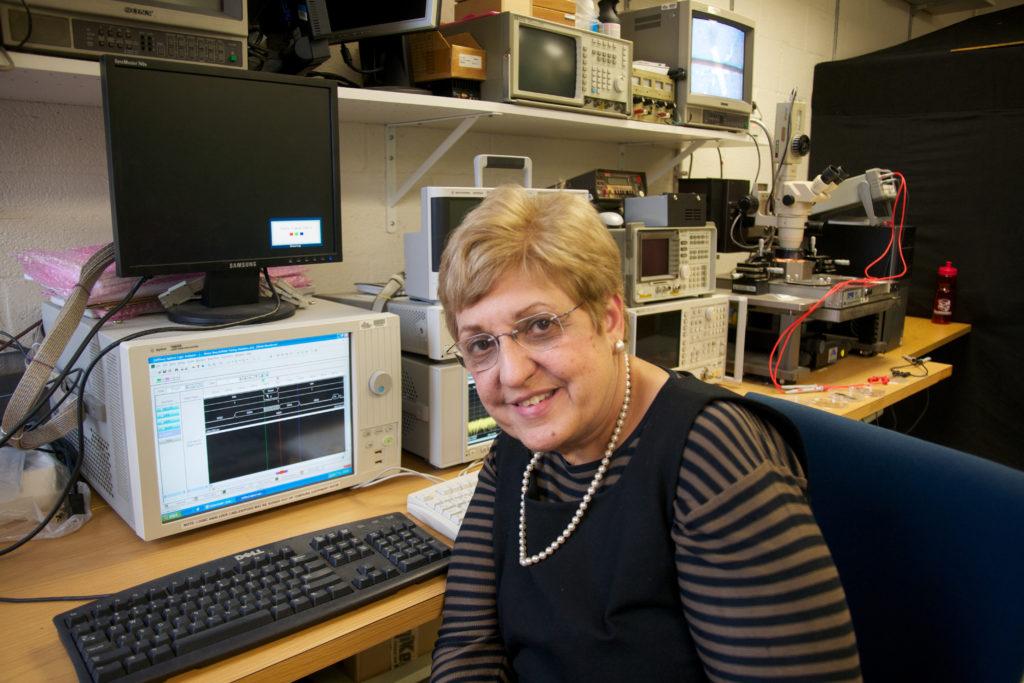

Mona Zaghloul, a professor of engineering and applied science, and her postdoctoral scientist Yangyang Zhao created a sensor in 2014 that could identify chemicals in the atmosphere, and they teamed up with epidemiology professor Jeanne Jordan to repurpose the device to detect COVID-19. Zaghloul and Zhao said the convenience and price of their device would allow people to test themselves for COVID-19 much more frequently than current tests permit.

Zhao said the pair recently received a call from Jerry Comanescu, a licensing associate in the Technology Commercialization Office, asking them to transform their sensing device into a COVID-19 tester. Using pre-existing technology, Zhao said he and Zaghloul began designing a nanosized, optical sensor that can test a human sample, like a cheek or nose swab, for COVID-19 and report results within a few minutes.

“The thing is for the testing of a specific virus – one-time testing doesn’t make sure you are safe forever,” Zhao said. “If you’re safe today, that doesn’t mean you’re safe for the next few months, so people have to be periodically tested or continuously monitored and thus such a device has to be low cost and convenient to use because otherwise no one can afford the cost.”

Zhao said the team made the sensing device from fused silica, a compound similar to glass and has small holes that detect different types of coronaviruses. He said once the virus binds to the sensor’s receptors, the local refractive index – or the speed at which light passes through a medium – will change, causing the color of the sensor to slightly change as well.

This change in light can’t be seen by the naked eye, but a smartphone camera is powerful enough to monitor the slight color change, Zhao said. He said artificial intelligence will then analyze the color change to identify if it is positive for the virus or not, and the information will then be sent to public health organizations through a cell phone application.

Zaghloul and Zhao said people using the device would need to purchase the cell phone application and a single-use sensor for about $2, based on the cost of the original sensor. They said they anticipate that the sensor will be finalized in three to four months.

“The low cost is a huge advantage because it makes it possible to be largely distributed to the community so people could be tested every day or every two days or every three days for that matter,” Zhao said.

Zhao said the team will use a receptor that captures all coronaviruses and then use AI to separate the viruses because experts currently don’t know whether COVID-19 antibodies differ from other coronaviruses like influenza. He said each type of virus will form a unique bond with the sensor’s receptor, producing a specific color light on the sensor for the cell phone camera to pick up.

“Let’s say you have two different viruses but three different sensors, then all of the sensors will give you a signal of the two different viruses,” Zhao said.

Since they just began transforming this device to detect COVID-19, Zhao said they must still conduct testing to ensure it is sensitive enough to detect the virus and able to differentiate between other viruses. He said once they prove the device works in the lab, then they can start performing clinical trials.

Zhao said the device then must receive Food and Drug Administration approval for commercialization.

Zaghloul and Zhao have been testing their device using a personal computer application, but they said they will eventually convert the operating system to a cell phone application. Zhao said the team’s goal is to send data from each test through an AI-based algorithm to be made accessible to public health officials.

“There might be some privacy concerns for that so we need to make sure that the app only collects necessary data because we also need to protect human privacy,” Zhao said.

Infectious disease experts said more people should be screened for COVID-19 on a regular basis, but this test would need to be highly sensitive to produce valid diagnoses.

Daniel Griffin, an infectious disease specialist at Columbia University Medical Center, said getting Zaghloul and Zhao’s sensor to work “would be fantastic and very helpful” because self-testing is “critical” to reach the threshold of testing experts predict is necessary.

“Self testing is critical considering the amount of testing we anticipate needing to be done,” Griffin said. “The challenge seems to be that people only do a good job if monitored, so this does require some technology and the ability to do it so people can be monitored via video during the collection of specimens.”

Dwayne Breining, the executive director of Northwell Health Labs in New York, said offering at-home testing gets “a bit tricky” because of the varying sample quality outside of health care settings. He said people could use a poor swab technique or results could be “gamed” by someone who wants a negative test result but added that the test could be useful in regular screenings that are becoming more common in places like nursing homes.

“It is likely that this type of test will be less sensitive than some other methods,” Breining said. “That may be OK depending on exact numbers, if there is a low risk level of the population being tested.”