The University is reducing the number of on-campus housing price brackets, officials announced at a Board of Trustees meeting earlier this month.

Trustees announced that the University will now offer students five housing cost models, instead of 17, for the 2020-21 academic year to streamline the number of pricing options for students. Assistant Dean of Students Seth Weinshel said officials reduced the number of options to simplify the housing selection process for students and level pricing with D.C.-area housing.

“The new rate structure compresses rates based on unit room type and density,” Weinshel said in an email.

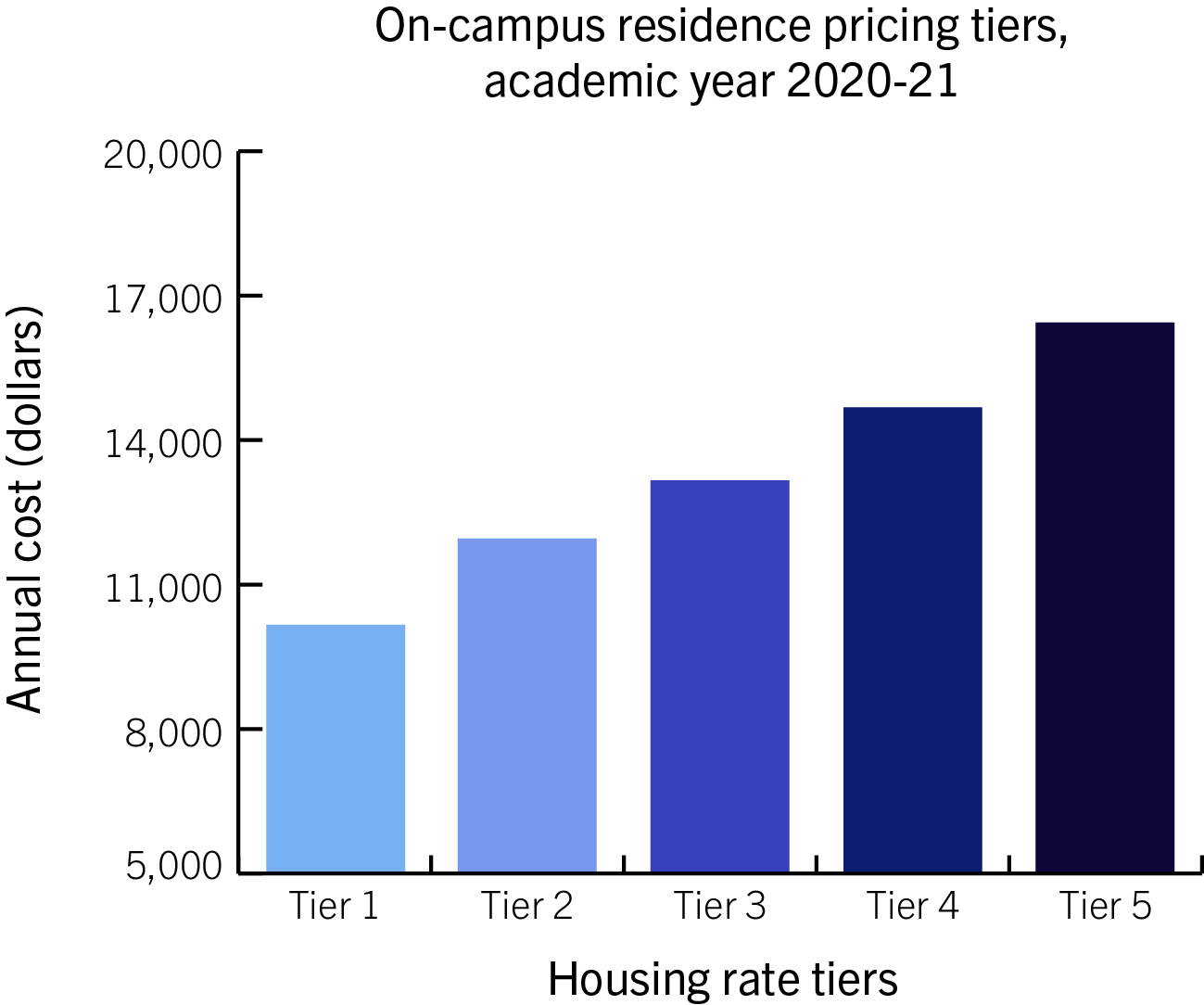

The price models are now divided into five tiers ranging from $10,120 to $16,400 for both underclassmen and upperclassmen residence halls, according to an email Weinshel and Assistant Dean of Residential Engagement Stewart Robinette sent to students.

Tiers one through three, which include halls like Madison and West halls, are available to all class years and cost students $10,120, $11,910 and $13,120, respectively, according to the email. Tiers four and five, which include Shenkman and South halls, are available to upperclassmen and cost $14,460 and $16,400, respectively, the email states.

Uzma Rentia | Hatchet Designer

Housing costs for this academic year included 17 options ranging from $9,530 to $16,840, the housing website states.

Weinshel said he worked with the Residence Hall Association and officials from “a number” of offices when deciding how to adjust the housing price model.

Living off campus in One Washington Circle will cost students $16,400 per year and The Aston, which is comprised of studio apartments, will cost students $11,910 per year, according to the GW Housing website.

Higher education experts said reducing the number of price brackets can help students determine how much to expect to pay each academic year.

Richard Vedder, an emeritus professor of economics at Ohio University, said housing and dining costs have generally been rising at a higher rate than real estate housing over the past few years.

A Hatchet analysis last year found that GW charges students thousands of more dollars than nearby apartment complexes. A recent report showed that the median sale price for homes in the Foggy Bottom and West End neighborhoods, where GW is located, has increased more than 40 percent since 2018.

“Housing costs for university students have risen dramatically more than housing costs in the general economy, and I cannot think of a good reason why that ought to be so,” Vedder said.

He said the reduction in costs could be a way to “disguise” an average hike in housing costs.

“They might have a sort of simplicity explanation,” Vedder said. “They may be using this in a way to just disguise some increases in the prices in housing, more and more.”

Dean Smith, an emeritus professor in the department of astronomy, biochemistry and physiology at the University of Hawaii, said universities usually increase housing costs to adjust for increases in utilities, like building maintenance, or an uptick in the price of its bonds. He said choosing from five pricing models will be less overwhelming for students than choosing from 17.

“If I was a parent or student planning my budget I would appreciate the opportunity to know as certain as possible, what are my costs going to be next year,” Smith said.

He added that the move won’t affect the University’s finances because the total cost of housing will remain about the same.

The University purchased $800 million worth of bonds in 2018, $100 million of which were allocated to residence halls.

“Definitely the cost that you’re paying is just reflecting the cost of the University,” he said. “That’s just the business model for all universities.”

Von Stange, the president of the Association of College and University Housing Officers-International, said the reduction in price brackets can help students more easily understand the price ranges they’re able to afford.

“There is no overall policy or philosophy on rate structures; it is handled on each campus,” he said in an email. “That being said, it is not surprising for a housing operation to reduce the number of housing options and associated prices.”

Stange said offering fewer housing options reduces confusion for students who want to clearly understand the total cost of attendance of their university.

“Today’s student wants a better ability to understand cost of attendance, and dozens of rates makes that determination more difficult,” he said. “Fewer rates means that students have a better idea of their cost of attendance, allowing them to make more informed choices.”