Traffic accidents on and near campus have decreased by nearly 15 percent over the past four years, according to District data.

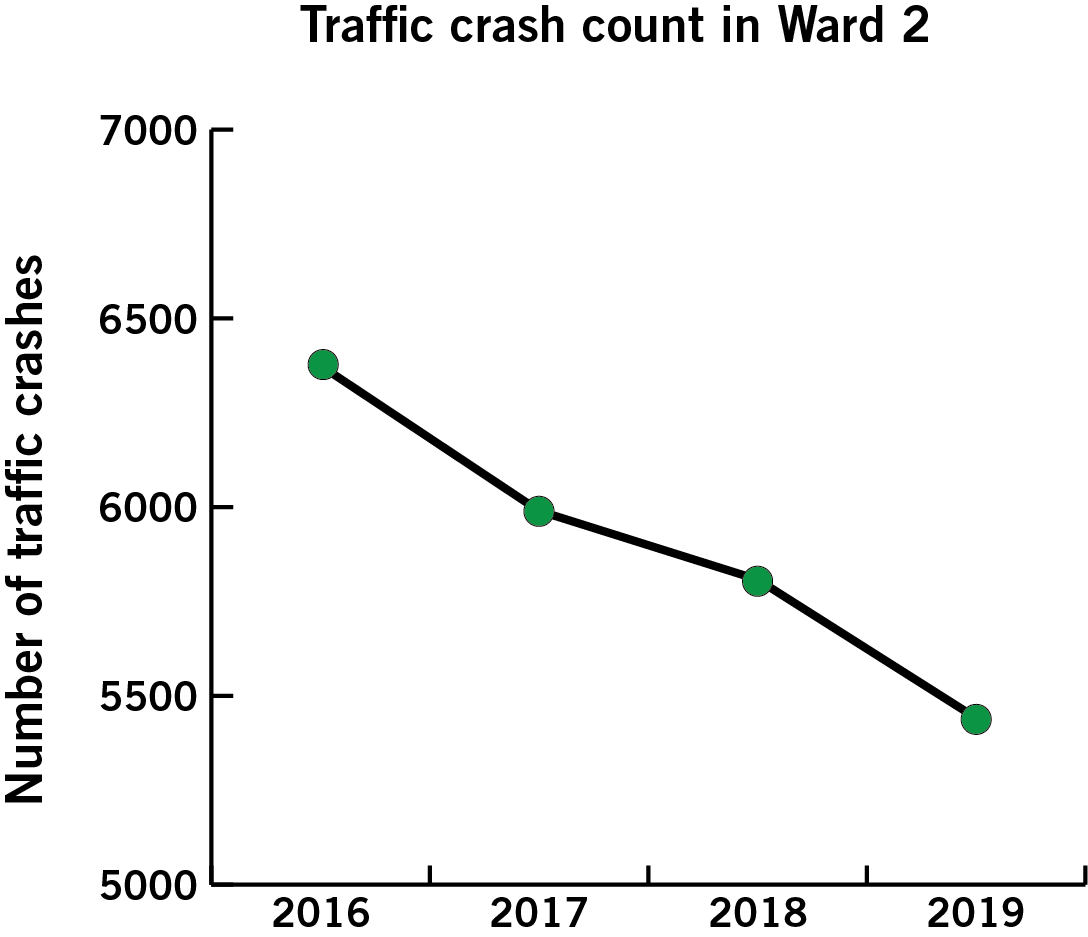

Ward 2, which has tallied the highest number of traffic crashes city-wide for at least the past four years, faced about 5,400 traffic crashes in 2019 – a slight dip from the previous year, during which about 5,800 crashes plagued the ward. Transportation experts said the decrease in crashes could be the result of transportation safety initiatives, like banning right turns on red lights and adding safe biking infrastructure, that the District Department of Transportation implemented last year.

Alexis Perrotta, a lecturer of public and international affairs at the City University of New York, said many traffic safety advocates view transportation as a safety “hierarchy,” under which pedestrians rank the highest, followed by cyclists and vehicles. Perrotta said safety measures, like banning right turns on red lights and constructing pedestrian waiting areas at intersections, help cities prioritize pedestrian safety over motor vehicles.

“That’s what makes our city run economically,” she said. “Dense cities require people on foot, they don’t foot people behind the wheel in the same kinds of numbers.”

Perrotta said officials could add bulb-outs, or extensions to curbs at intersections, to both provide added space for pedestrians to wait to cross the street and slow cars down at intersections, decreasing the chance for pedestrian-vehicle crashes.

DDOT recommended adding bulb-outs at several intersections around the city, Greater Greater Washington reported in 2016.

Alyssa Illaria | Graphics Editor

Perrotta added that building protected bike lanes in cities contributes to fewer fatalities because drivers are aware of bikers riding on the street.

DDOT and the Foggy Bottom and West End Advisory Neighborhood Commission have been negotiating the route for a protected bike lane running through Foggy Bottom for more than a year and are planning to start construction on the bike path in 2020.

“Seeing someone on a bicycle when you’re driving slows a person who’s driving down, and that’s important,” she said. “Anytime you slow down, you’re going to have fewer fatalities.”

Kara Kockelman, a professor of civil, architectural and environmental engineering at the University of Texas at Austin, said the drop in Ward 2 crashes is likely the result of District traffic safety initiatives. She said safe streets encourage residents to use several transportation methods other than walking.

“If you feel safer, they often will bike more, walk more and let their children bike and walk more, which is nice,” she said.

DDOT spokeswoman Lauren Stephens did not return multiple requests for comment.

Total traffic fatalities decreased in the District for the first time since 2016, but some transportation experts said traffic death rates tend to fluctuate, and there may not be a specific reason for the decrease

Vision Zero, which Mayor Muriel Bowser committed to in 2015, aims to eliminate all traffic fatalities by 2024.

Ian Savage, a professor of economics at Northwestern University, said the 25 percent drop in the District’s traffic fatality count – from 36 in 2018 to 27 in 2019 – is “objectively” positive but doesn’t necessarily prove that the city’s efforts to curb traffic deaths have been effective. He said D.C.’s overall traffic fatalities are too low to determine a specific cause for the drop.

“When you’re dealing with things that are under 30ish in terms of number, then you expect to see quite a variation from year to year,” he said.

Among those killed in traffic crashes this year were biking advocate Dave Salovesh, who was killed while riding his bike in Northeast D.C., and two people experiencing homelessness in Foggy Bottom, who were killed by a speeding driver in Foggy Bottom.

Savage said D.C. officials likely need to work on a “micro” level to continue the city’s downward traffic fatality and crash trend, meaning DDOT could investigate individual intersections.

“The answer here is that probably everything you’re going to do is at a very local level, I mean a really micro level, in the sense that you’re going to look at individual intersections and things and you’re going to find that many of these are just badly designed,” Savage said.

Some experts attributed the lofty overall traffic crash numbers in Ward 2 to the large concentration of traffic in downtown D.C.

Najmedin Meshkati, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of Southern California, said Ward 2 likely has a higher rate of traffic crashes in the city overall because the area encompasses most of downtown D.C., where traffic is concentrated.

He said the drop in Ward 2 traffic crashes could have resulted from city-wide safety improvements, like additional signage or street markings.

“This is a very obvious direct one-to-one relationship,” he said. “If you don’t have congestion, and you don’t have that much traffic, there is much less chance of accidents.”