Updated: Sept. 30, 2019 at 11:08 p.m.

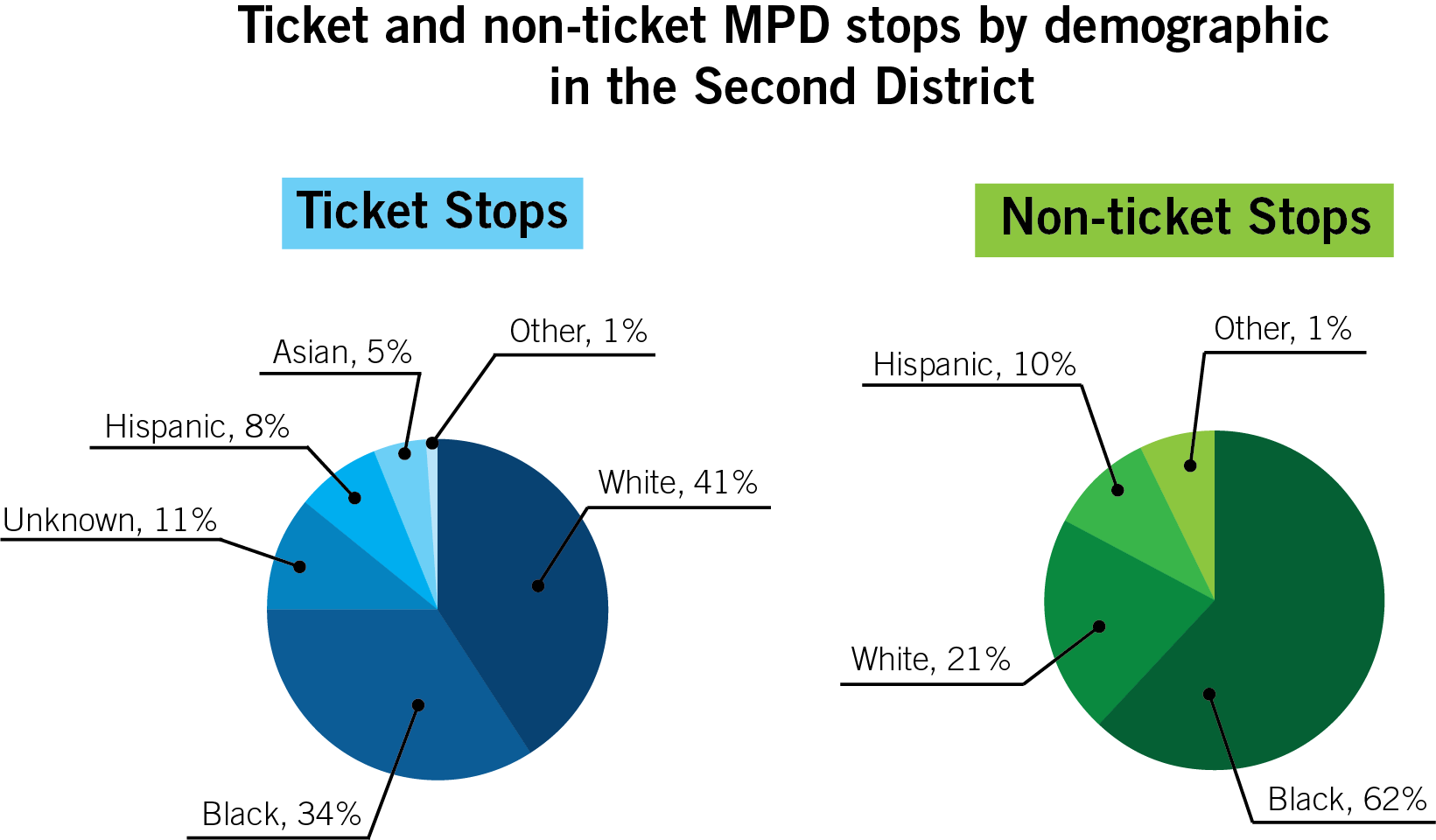

Metropolitan Police Department officers disproportionately stopped black individuals in the Second District, where GW is located, over the course of four weeks this summer.

Sixty-two percent of the non-ticket stops made in the Second District, which encompasses neighborhoods like Foggy Bottom and Georgetown, were made for black individuals in a four-week period, according to a stop and frisk report MPD released after years of delay earlier this month. Criminal justice experts said police departments should engage in community outreach to minority communities to curb racial disparities in policing.

The Second Police District encompasses parts of Wards 2, 3 and 4, where black residents account for 9, 6 and 52 percent of the population, respectively, according to Census Reporter, a website that gathers U.S. demographic data.

Alyssa Ilaria | Graphics Editor

Source: Metropolitan Police Department

MPD spokeswoman Alaina Gertz said the data collected over the four-week period is insufficient to draw conclusions from about racial bias in police stops. Gertz said MPD will release stop data for all of 2019 at the beginning of 2020 and release stop data every six months after that.

“MPD is committed to ensuring that each police stop meets its high standards for fair and constitutional policing and demonstrates respect for the individual stopped,” she said.

In other police districts, black individuals comprised higher proportions of non-ticket stops, totaling 97 and 98 percent in the Sixth and Seventh districts, respectively, where black residents make up larger portions of the areas’ populations.

The NEAR Act, which the D.C. Council passed in 2016, requires MPD to collect comprehensive data on police stops to build transparency and increase community trust.

In May 2018, the American Civil Liberties Union of D.C., Black Lives Matter D.C. and the Stop Police Terror Project D.C. sued MPD and Mayor Muriel Bowser for failing to collect stop data. The latest release of data comes nearly two months after a D.C. Superior Court judge ordered MPD to comply with the NEAR Act and track the race of each person officers stopped.

Black individuals constitute just under half of the District’s population but accounted for 86 percent of total non-ticket stops MPD officers made citywide during a monthlong report MPD released earlier this month. Gertz said the department will work with independent researchers to further analyze the data and additional stop data before drawing conclusions about the disparities.

Gertz said only 5 percent of the roughly 11,600 individuals that police officers stopped during the reporting period received protective pat downs in addition to being stopped. Nearly 90 percent of the individuals who were subjected to protective pat downs during their stops were black, according to data posted on the department’s website.

The department defines protective pat downs as limited protective searches conducted when an officer has “reasonable suspicion” that an individual is involved in criminal activity.

In the Second District, only 4 percent of police stops resulted in a protective pat down, compared with 5 percent of stops resulting in a protective pat down citywide, according to MPD’s data.

Scott Michelman, the legal co-director of the ACLU of D.C., said the newest data supports previous ACLU findings, which reviewed police data collected from 2013 to 2017 and demonstrated that black individuals are more likely to be stopped than any other race.

The ACLU will work closely with Black Lives Matter and Stop Terror to reform police practices but is not clear on specific next steps for reform, Michelman said.

“We are continuing to analyze the data, but already these numbers raise grave questions about whether the D.C. police are over-policing community members of color,” Michelman said. “We will continue to seek answers and fight for reform.”

Experts on racial disparities in policing said police departments can utilize community policing tactics to keep trust between officers and residents.

Richard Rosenfeld, a professor emeritus in criminology at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, said police departments should hold continuous meetings with members of minority communities and establish a set of agreed-upon conditions for where to place police officers in the city to alleviate concerns that minorities are over-policed.

“Basically, you hear all of the time, ‘With all these cops around, you would think we wouldn’t have so much crime. Where are they when we really need them?’” Rosenfeld said.

Renee Hutchins, the dean of the University of the District of Columbia’s David A. Clarke School of Law, said MPD’s racial disparities in the Second District are “grossly disproportionate” to the black population in the area.

Hutchins said she hopes MPD can turn to other cities that have been successful in reducing racial disparities in policing to find ways to curb the disparities.

“There are smart people thinking about these issues that can help us figure out how to move to a different place, and I would hope that MPD would aggressively lean into those solutions, as opposed to hunkering down and becoming defensive about the findings,” she said.

Brendon Lantz, a professor at Florida State University, said disproportionate policing of black residents can have amplified effects on minority populations who may believe police treat them unfairly.

“More broadly, because police act as gatekeepers, the decisions that they make can cause reverberations throughout every stage of the criminal justice system,” Lantz said. “If these decisions are racially biased, they increase racial disparities in incarceration, which may lead to increased community and family disruption among minority communities.”

This post was updated to correct the following:

A previous version of the story misspelled the District of Columbia’s David A. Clarke School of Law. It is now corrected. We regret this error.