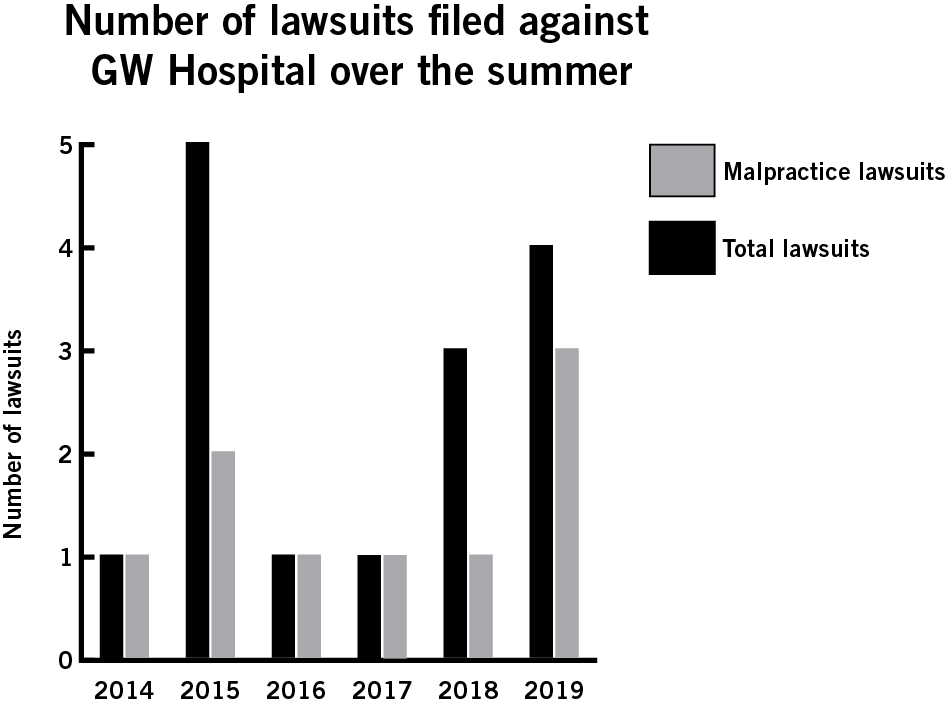

The GW Hospital withstood the greatest number of malpractice lawsuits this summer compared to the last five summers.

Since the last day of spring classes, complainants sued the GW Hospital four times in the U.S. District Court and in the D.C. Superior Court, three of which alleged medical malpractice. The hospital has faced only one malpractice case each summer since 2016.

A man most recently sued the hospital last Monday alleging a GW Hospital nurse improperly removed a catheter from his body in August of 2016. A man sued the hospital in July claiming that hospital staff improperly treated him for an ulcer.

A woman filed suit against the hospital at the end of July alleging that GW Hospital doctors improperly removed a stent – a tube placed in an artery to aid healing – in her chest, moving her colon. The mistake required the woman to undergo additional surgical procedures, according to the complaint.

Alyssa Ilaria | Graphics Editor

Christine Seawright, a hospital spokeswoman, did not return multiple requests for comment.

Experts in health law said an uptick in malpractice cases cannot always be attributed to a single issue, but hospitals should adjust standardized treatment practices to reduce the risk that a patient brings a suit against them.

Michael Shapiro, a law professor at the University of Southern California, said potential effects of an increase in malpractice cases depends on the aspects of each case, like the type and damages.

“Responses to an increase in suits, in general, or at a particular institution, can vary widely and may even be paradoxical in a few cases,” Shapiro said in an email.

He said hospitals could buy more insurance, raise charges for patients and “reduce compensation” to staff to lower the chance of a medical malpractice case. Hospitals can also update safety and training procedures, lower staff pay or increase medical charges to cover legal costs, Shapiro said.

Jeff Rubin, an economics professor at Rutgers University who specializes in health economics, said hospitals should re-evaluate their routine practices, like double-checking patients’ vitals and medications, when there is an uptick in malpractice lawsuits.

A report from CRICO Strategies – the medical liability insurance provider for Harvard University medical institutions – found that nationwide medical malpractice cases are decreasing, but legal costs for hospitals are increasing. From 2007 to 2016, the rate of malpractice lawsuits per 100 doctors decreased by 27 percent, according to CRICO’s research.

Defending a malpractice lawsuit declined 3.5 percent annually from 2007 to 2016, from $36,000 to $46,000, according to CRICO’s research.

“What you’d like to hope is that it affects their care level, in that they’re going to ensure that their employees are doing things that are aligned with better care,” Rubin said.

He said hospitals could emphasize patient safety and ensure procedures are in place for checking patients’ vitals and medications to curb the possibility of a malpractice complaint against the hospital.

“If you have a particular physician that is doing something a little more risky than normal, that may mean the hospital is getting dragged in, simply because you’d be foolish to sue the physician and not the hospital as well,” Rubin said.

He added that an increase or decrease in malpractice lawsuits could be attributed to a failure to diagnose or properly treat a patient, and that GW’s rate of lawsuits per summer is extremely low relative to other U.S. hospitals.

“It may well just be they happen to have three more angry than normal people this year,” Rubin said. “But there’s no basis in fact that the hospital is doing anything more or less wrong.”

Kathryn Zeiler, a law professor at Boston University, said university hospitals are more likely to have lawsuits against them because physicians-in-training work at the hospitals, which often means less experienced staff members treat patients.

She said many hospitals provide means for doctors to report adverse events that could result in a claim against them to the risk management team before the patient has filed a formal claim.

“The medical staff and the doctor will apologize to the patient,” Zeiler said. “That’s a big component of these new systems, or new ways of dealing with these claims, to offer an apology.”

She said that many hospitals are moving toward using this system to cut litigation costs. Zeiler said D.C. law does not cap the amount of money that juries can grant plaintiffs, which leads to more verdicts than settlements or dismissals.

“It’s generally when the patient lives and has ongoing medical costs that add up over a lifetime, or lost wages add up over a lifetime,” she said. “Those can be high damages claims.”

Ciara Regan contributed reporting.