The University wants donors to give GW a spot in their wills.

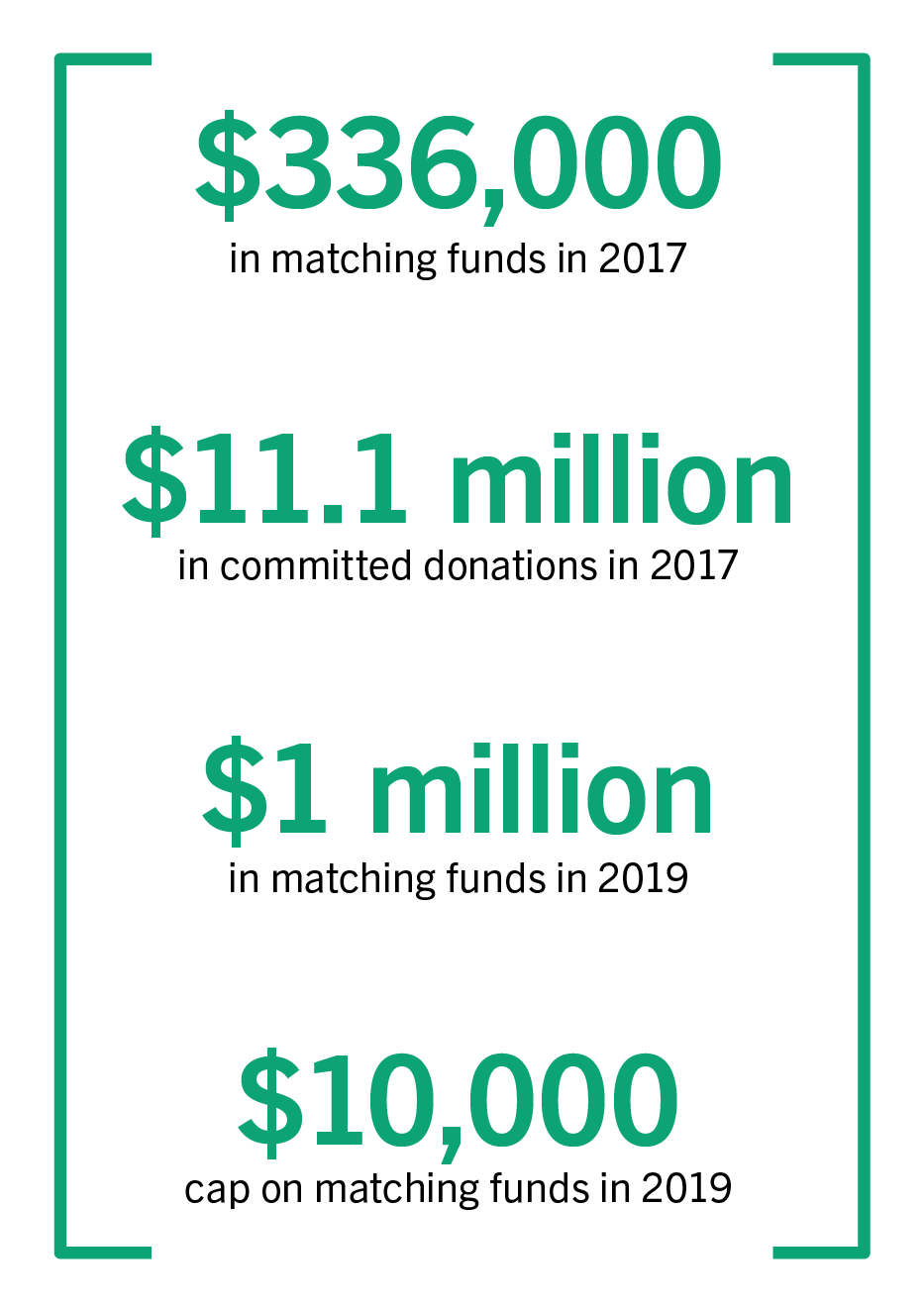

Officials are reviving a planned donation campaign encouraging individuals to name GW as a beneficiary in their retirement plans, wills or living trusts. The campaign, last hosted during GW’s largest-ever fundraising push two years ago, documented $11.1 million in planned gifts – and officials said they are raising the stakes this year.

“With results that successful, we wanted to offer a second edition to encourage even more GW supporters to take part,” the challenge’s website states.

Throughout this year’s fundraising challenge, donors who pledge late-in-life gifts to GW will receive a matching gift of $1 for every $10 they donate to any GW fund like scholarships or specific programs. Officials are capping the matching funds at $10,000 and offering a total matching pool of $1 million – more than double the $336,000 available in 2017, according to the challenge website.

The $1 million in matching funds comes from the unrestricted donations of the estates of two alumni, Joan Colbert and Douglas Mitchell, who graduated from the Columbian College of Arts and Sciences in 1961 and the School of Business in 1993, respectively.

Donna Arbide, the vice president for development and alumni relations, said the matching challenge was inspired by similar challenges started by other nonprofits. When the 2017 challenge started, a “handful” of other schools had done similar challenges, but now more schools are toying with planned giving campaigns, she said.

Emily Recko | Graphics Editor

Source: Legacy challenge website

She said the challenge did not happen in 2018 because officials did not have the resources and time for a yearly event.

“It is not intended to be an ‘annual’ event given the planning and administrative work required, as well as the need to have a sufficient pool of matching funds available to support a challenge,” she said in an email.

She said the challenge mostly targets donors aged 65 and older who will be reached through a broad marketing campaign including advertising in the GW Magazine and other GW outlets.

“While GW alumni, faculty, staff and friends of all ages may make GW the beneficiary of their estate plans, donors must be at least 40 years of age to document a planned gift and participate in the Legacy Challenge,” she said in an email.

She declined to say how much money has been raised or how many people have made donations so far.

Planned giving experts said allowing more donors to participate in a giving challenge helps create a broader base of support for the University, which could help officials ahead of the launch of the University’s next capital campaign in 2021.

Officials announced a series of new goals in the fall aiming to build the University’s donor base ahead of the campaign, including retaining 64 percent of donors and hitting 16,000 alumni donors by the end of the fiscal year.

Tom Yates, the executive director of gift planning at Temple University, said planned giving campaigns are effective because the alumni office can identify donors who have large inheritances to donate. Those kinds of donors do not often think to tell the University that they are putting GW in their will, or they consider it private information, preventing staff from knowing which donors can be courted for more funds.

“These challenges are a way for universities to kind of draw out those donors, get them to document the bequest and celebrate it,” he said.

He said increasing the size of and capping the matching fund could mean that the University had more donors that wanted to participate in the last challenge, but the fund ran out before they could participate.

Yates added that fundraising progress made in the couple of years leading up to the launch of a major capital campaign are typically counted toward the campaign goals. He said those campaigns typically include a goal for planned giving because the gifts help the University maintain long-term financial security.

“Basically, you’re building a pipeline for the future,” he said. “Use that campaign as an opportunity to talk up bequests amount your donor base so you’re not really raising money for today but for decades down the road but you’re using the campaign as a vehicle to do that.”

Kathy Saitas, the senior director of gift planning at Reed College, said planned giving challenges can help colleges avoid situations in which officials suddenly receive a big sum of money in someone’s will but they are not able to accept it. If donors do not consult with a university before designating some of their estate, they may pick a cause that does not make sense, she said.

If the University cannot carry out the donor’s wishes, the estate then goes to the next person or institution designated in the will, Saitas said.

“If you don’t have those conversations in advance, then your institution can end up in a really weird place where it ends up doing something that doesn’t make sense with money, not accepting the money,” she said. “So identifying, really telling people, ‘Hey, if you plan to do something for the college in your estate plan, it’d be great if you had a conversation with us in advance.’”