The sustainability office achieved 14 of the 56 eco-friendly goals officials set for themselves 10 years ago, while about 67 percent of the remaining objectives are ongoing.

The Office of Sustainability’s first progress report in a decade found that GW has kept waste out of landfills and generated energy from low-carbon technology. Officials said they will now focus on cutting carbon emissions, reducing water consumption and expanding recycling on campus by educating students about sustainable practices and creating more eco-friendly academic and advocacy programs.

The report, released on Monday, details the progress of 22 short-term goals and 34 long-term targets, like conducting a light pollution study and reducing water consumption by 25 percent, respectively. The University has completed 11 short-term goals but missed five, while officials have checked off three long-term objectives. Nine goals are currently in progress, according to the report.

Meghan Chapple, the director of the office, said the report reflects efforts to be transparent with the community and highlight the University’s accomplishments and challenges. Officials have not always provided updates on their goals for sustainability and for years stayed quiet on their water conservation goals.

[gwh_image id=”1079728″ credit=”Emily Recko | Graphics Editor” align=”right” size=”embedded-img”]Source: SustainableGW Progress Report[/gwh_image]

“We are doing this so that GW students, staff and faculty know how GW is doing because we are committed to sustainability,” she said.

Hitting the mark

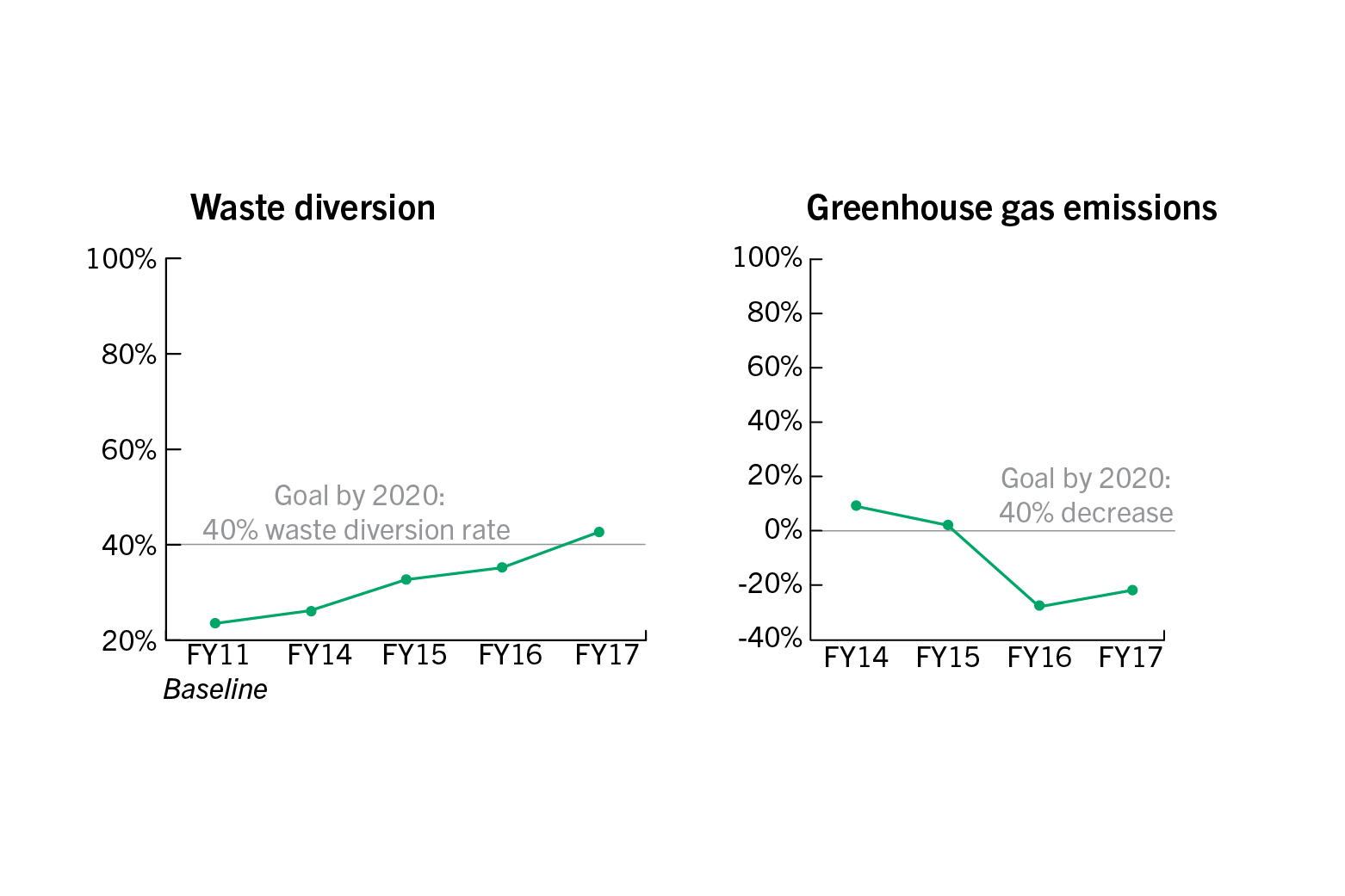

The office is on track to cut 40 percent of carbon emissions by 2025, with a 22 percent reduction in emissions since 2008, but Chapple said the office must continue to combat sources of greenhouse gas emissions if the campus will achieve carbon neutrality by 2040.

The University’s biggest emissions contributor is air travel from faculty flying to conferences and students studying abroad, she said. Chapple said the office is exploring other universities’ programs to plant trees and other greenery to offset the amount of carbon produced from those emissions – something officials first announced last semester.

“The nice thing is that they have already started to experiment with things that we can jump on board faster than they were able to do it,” she said.

GW also surged past its goal of reducing landfill waste by 40 percent by increasing composting projects and reusing paper, according to the report. The University launched its composting program last fall on the main campus and expanded to the Mount Vernon Campus last month.

Tara Scully, the director of the sustainability minor, said progress is not only coming from the sustainability office and its staff. The number of students participating in the office’s student sustainability advocacy program Eco-Reps has increased by 135 percent in three years, according to the report.

Sydney Kleingartner, a freshman in the Eco-Reps program, said the students are on the front lines in pushing their peers to change their behavior. Students are more likely to listen to suggestions from their friends about how to be more sustainable, she said.

“When you come into college and you don’t know, you think it’s too late not to know,” she said. “Because I’m more aware of it, I make my friends more aware of it.”

Emily Recko | Graphics Editor

Source: SustainableGW Progress Report

Izzy Moody, the Student Association’s vice president for sustainability, said students are often the “driving” force behind environmental change on campus.

Student leaders have advocated for more sustainable practices in recent years, including an ongoing effort from Fossil Free GW to push the University to relinquish its holdings in fossil fuel companies. With the help of SA leaders, administrators created a $2 million sustainable investment fund last spring.

“Whether we are vocalizing our desire for more sustainably, ethically sourced affordable food on campus or demanding a future without dirty energy, our actions absolutely shape GW’s vision for its own sustainable goals,” she said in an email.

Missing the grade

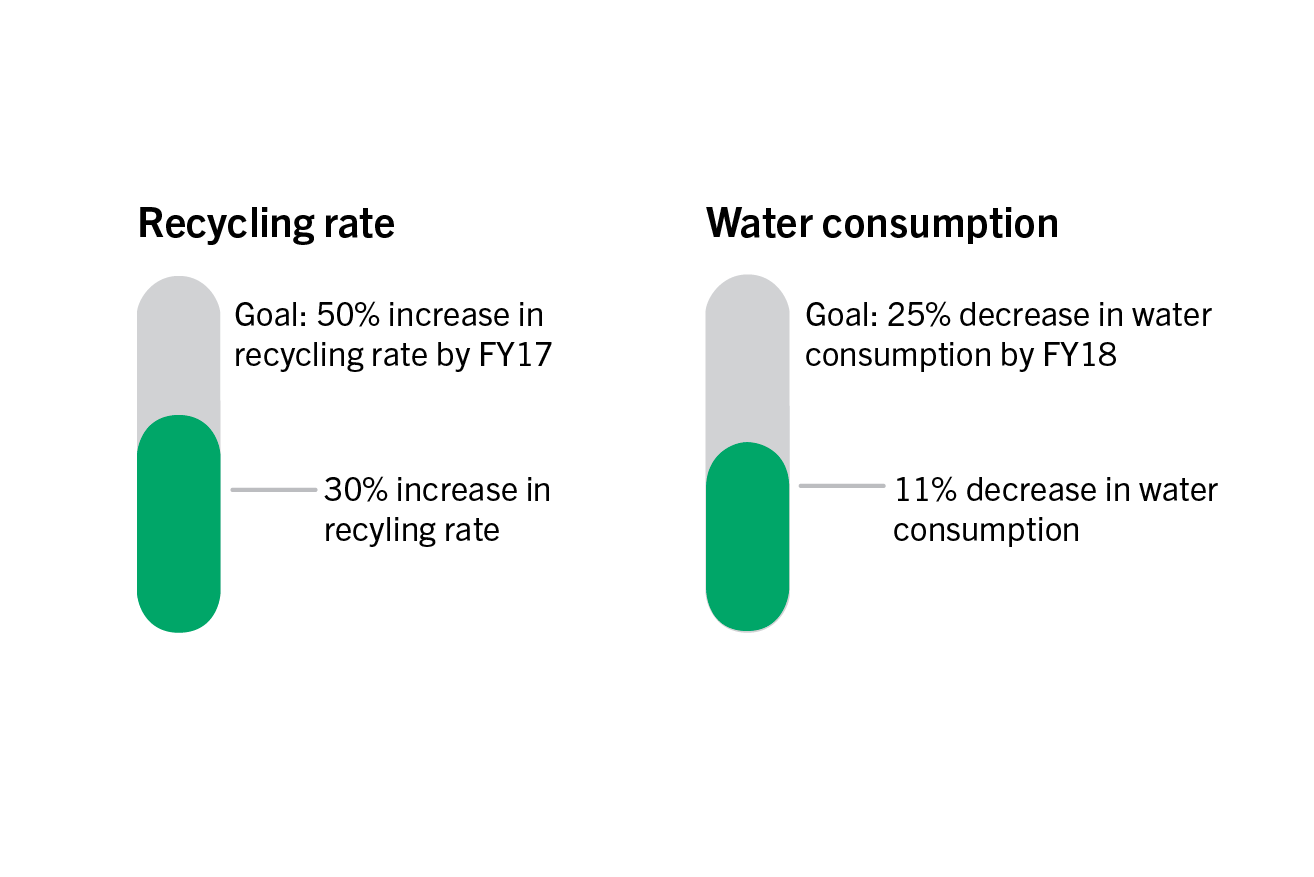

But GW didn’t achieve all of the progress officials had hoped for. The University fell short of its goal to increase recycling rates to 50 percent by fiscal year 2017. Since 2008, GW has improved recycling numbers to hit about 30 percent.

Chapple, the director of the sustainability office, said the office is exploring ways to educate more students and employees about properly recycling their trash. She said officials are working on launching “living labs” by 2021 where students can build sustainability projects to improve campus life.

Chapple added that the office has struggled to meet its goal of reducing water consumption by 25 percent by fiscal year 2018 but is re-evaluating the goal altogether. GW had reduced consumption by 11 percent in fiscal year 2017, according to the report, but Chapple said the cooling towers that provide air conditioning on campus in the summer are slowing down improvement.

The cooling towers use water resources, but it is difficult to cut back because of D.C.’s humid climate, she said.

Despite having audited the litter on campus, officials have not yet discovered any solutions to reduce litter. GW’s ReUse program website, a program that finds other uses for unwanted University furniture and property, and an environmentally friendly chemistry lab, which were set to begin operations by 2013 and 2015, respectively, have not begun, according to the report.

Emily Recko | Graphics Editor

Source: SustainableGW Progress Report

Moving forward

Robert Orttung, the director of research at the office and an associate research professor of international affairs, said he hopes to find more faculty research projects on campus that can be used to improve sustainable practices.

“Much of the research done on campus might not have implications for operational sustainability, but we hope to encourage more discussions about how we might be able to do this kind of thing among faculty, staff and students going forward,” he said in an email.

Chapple, the director of the office, said officials plan to work with GW’s social media dining representatives to reach out to GWorld dining vendors this semester to develop a network of sustainable food vendors on campus. She said staff will talk to vendors about what standards – like food sourcing – the office can set that vendors can practically meet and be considered sustainable.

“The goal that I have is that we can make it more transparent, just like this report is transparent, how these vendors are performing on sustainability and what are they willing to share and publicize,” she said.

Officials pushed for more food vendors to use products from local and sustainable sources in 2016.

Scully, the director of the sustainability minor, said officials have also discussed launching a sustainability major, but the idea is in early conversations. The minor currently has about 220 students, but officials would have to restructure the minor’s curriculum to accommodate a major, she said.

Officials have been evaluating the minor over the past semester and collecting feedback from students and faculty who teach courses in the minor.

“Taking that next step requires us to reformat the minor to then be able to scale it to a major,” she said. “We’re working on those ideas and trying to bat around how this would work out.”

Scully added that some forward-looking sustainability projects – like building ecobricks, or plastic bottles filled with plastic waste that can be used as support for buildings – are already underway.

Sophomore Sophia Duchin said she went on an Alternative Breaks service trip to Costa Rica with Scully last year where she learned how to make ecobricks. Duchin said the bricks keep plastic out of landfills without creating carbon emissions in the way that recycling does.

“It’s a fulfilling way to do something tangible that you can make this thing – you can hold it in your hands and know that it is helping stop climate change,” she said.