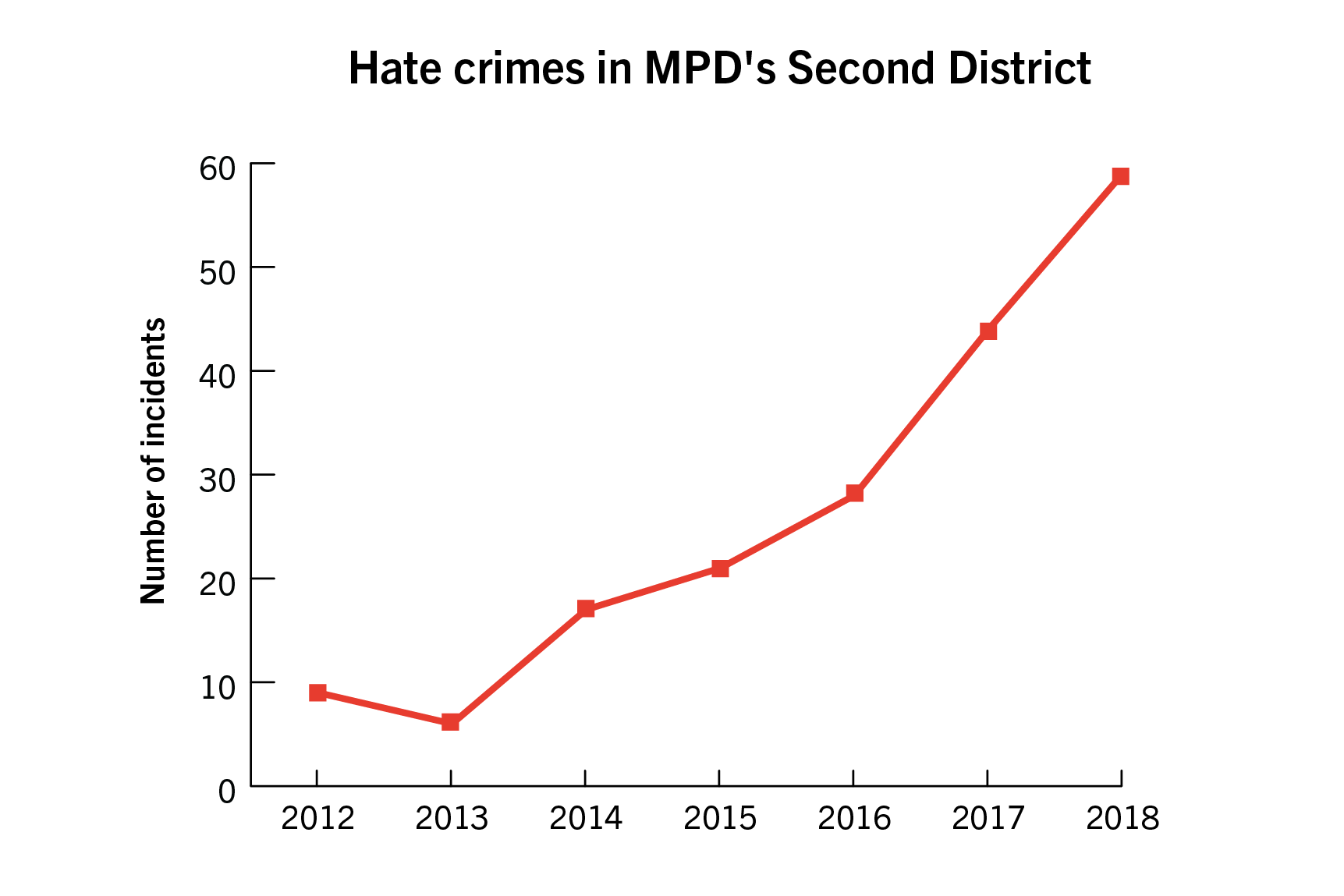

Hate crimes in the Metropolitan Police Department’s Second District, which includes Foggy Bottom, have increased by nearly 900 percent over the past five years, according to newly released MPD data.

Fifty-nine hate crimes were reported in the Second District last year compared to six in 2013, according to the MPD data. Criminal justice experts said the increase in hate crimes is likely linked to an increase in anti-immigrant rhetoric nationwide, coupled with higher reporting rates and recent police training about classifying the crimes.

Hate crimes, also known as bias-related crimes, are defined as acts that demonstrate the perpetrator’s prejudice based on factors like race and religion.

Threats and simple assaults accounted for about half of the Second District’s hate crimes in 2018. The highest number of assaults in the Second District prior to 2018 was eight – but last year, that number jumped to 14.

There were 16 reported threats in 2018, a slight increase from the 12 reported in 2017 and the highest number in the past five years. The 16 reported incidents of damaging, defacing or destruction of property are six more than the number reported in 2017 and the highest in the past five years.

Brett Parson, a lieutenant and commander of MPD’s special liaison branch, said a four-hour MPD training in 2015 reviewing policies and procedures for investigating, reporting and documenting hate crimes could contribute to the increase in documented hate crimes because police are better trained on the topic.

Emily Recko | Graphics Editor

Source: MPD data

He added that increased media coverage of hate crimes and growing police department efforts to educate communities about the topic have contributed to higher rates of victims reporting bias-related incidents to police. He added that MPD has an “extensive set of operations and protocols” to build relationships with “vulnerable” communities in D.C., including LGBTQ and black communities.

“Bias-related crimes become more and more of an issue in the media, social media – and in our society, it sees itself,” Parson said. “More and more people report.”

Twenty-two reported hate crimes were based on ethnicity – the leading type of hate bias. There were 14 hate crimes based on race in 2018.

Sexual orientation, religion and gender identity and expression each had five reported hate crimes. One hate crime listed homelessness as the type of bias. There are seven types of hate bias included in data for the Second District.

No crimes listed political affiliation as a type of bias until 2015. There were two, five and seven hate crimes attributed to political affiliation in 2016, 2017 and 2018, respectively.

Crimes are also categorized by types of offense, including threats and assaults, but Parson said displaying symbols wasn’t categorized as an offense until 2017. That year, MPD discovered a “little known” statute in the D.C. code specifically referring to hateful symbols like swastikas. He said MPD previously categorized those hate crimes as defacing property.

“As time goes on and we become more and more efficient and proficient in reviewing these crimes and educating our members, we have become even more technical in how we classify crimes,” he said.

He added that MPD is responding to hate crimes by building relationships with members of the D.C. community to educate residents and encourage them to report crimes.

“We are working with community groups to try and help make people aware of the trends that are occurring, help them protect themselves from crimes that they may be able to prevent and more importantly, teach their children that this type of behavior is not a D.C. value and will not be accepted,” he said.

Maria Tcherni-Buzzeo, an associate professor at the University of New Haven’s College of Criminal Justice and Forensic Sciences, said the increase in hate crimes might be caused by increased debates about immigration policy. She said both the United States and other developed countries have “fears” that immigrants take away jobs and lower wages.

“This could be fueled by the increasing awareness of immigration or immigration issues that clearly fueled the divide in the country that brought President Trump into power,” Tcherni-Buzzeo said.

Brendan Lantz, an assistant professor at Florida State University’s College of Criminology and Criminal Justice, said hate crimes are rising in part because of the “general increase in comfortability” with white nationalism exhibited at events like the Unite the Right rally in 2017.

“A lot of them were white nationalist groups that felt comfortable organizing in this space because they felt comfortable in what they were standing for,” Lantz said. “And that’s indicative of a wider issue where white people feel threatened by immigration, by conspiracy theories and all sorts of things like that.”