Public health researchers are trying to fight back against obesity, climate change and malnutrition – all at the same time.

Two public health researchers teamed up with 41 other researchers from 14 countries to publish a study last week arguing that obesity, climate change and malnutrition are interrelated global epidemics. The researchers issued a series of nine recommendations to address all three issues jointly, including dedicating billions of dollars to support a global “food fund” that would promote healthy and sustainable diets and pushing the United Nations to develop ways to monitor policies combating malnutrition and greenhouse gas emissions.

The report was produced by the Lancet Commission on Obesity, a committee of researchers from different parts of the world dedicated to identifying problems and finding solutions related to obesity.

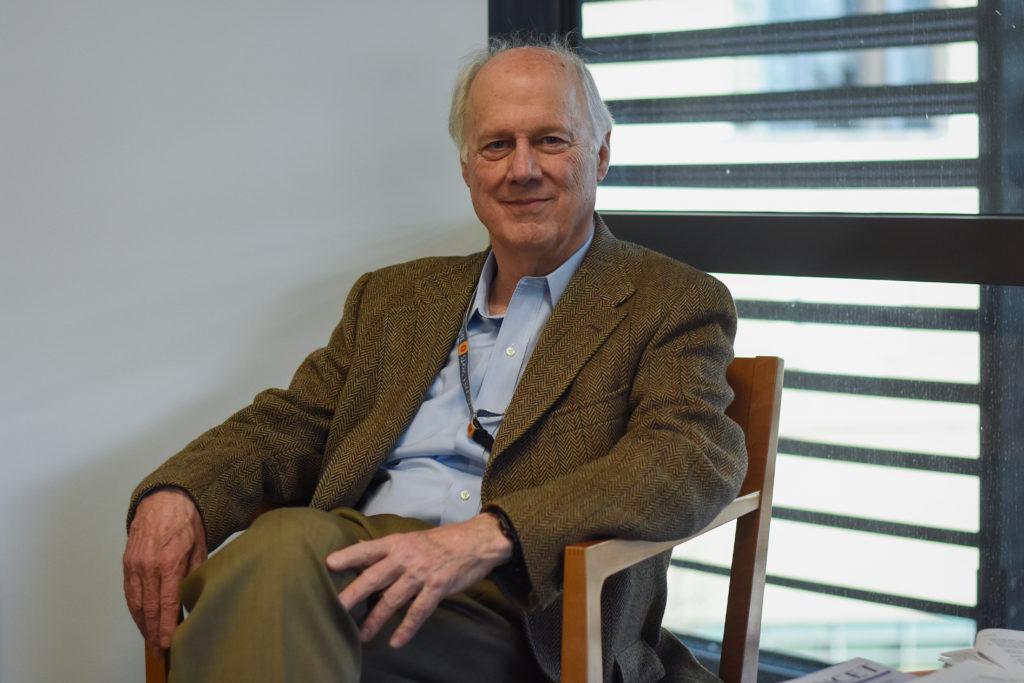

William Dietz, the director of the Sumner M. Redstone Global Center for Prevention and Wellness and a professor of prevention and community health in the Milken Institute School of Public Health, said the commission that produced the study was comprised of researchers from more than 20 different disciplines.

Dietz said the idea of a “syndemic” – two or more connected global epidemics – is not new, but the commission redefined and expanded the term’s meaning. The word was previously used to describe the interaction between health and poverty before the commission used it to describe at least two interrelated diseases that are affected by external factors, he said.

Dietz said substantive action must begin on the individual and local level to influence governments to change. He said individuals are increasingly demanding sustainable food, moving the world in a positive direction.

“I hesitate to call it a social movement because I don’t think it’s widespread enough, but that’s where we need to go,” he said.

Dietz said people should attempt to find “double-duty” or “triple-duty” solutions – actions that would limit the damaging effects of more than one of the epidemics at the same time.

He said a decreased demand for meat would result in reduced production, cutting greenhouse gas emissions. Less meat consumption would also reduce the risk of obesity, colon cancer and cardiovascular disease, he said.

“If you decrease reliance on cars and go to public transport or physical transport, like walking or biking, you prevent obesity and reduce greenhouse gases,” he said.

Michael Long, an assistant professor of prevention and community health who contributed to the study, did not return a request for comment.

Vivica Kraak, an assistant professor of food and nutrition policy at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, said she attended the first meeting for the commission at GW in February 2016. With the exception of a second meeting at the University of Auckland in July 2017, most of the work was completed remotely, she said.

She said the commission was broken down into about eight groups, with each focusing on a different theme, like health care services.

“No one intervention or strategy is going to be able to bring it to the tipping point or reverse the problem,” she said.

Kraak said her work group, which focused on the right to well-being, studied human rights literature and international treaties related to people’s right to adequate and healthy food.

“We need to think about protecting people’s environments so that they can optimize their health,” she said.

Alexandra Morshed, a doctoral candidate at Washington University in St. Louis, said she was invited to serve as one of the fellows on the commission to learn about the research process and the connection between the three wide-ranging crises.

“We are going to be on the next generation that pushes this new approach to addressing climate change, obesity and undernutrition forward,” Morshed said.

She said bringing together a wide range of researchers allows each researcher to learn from a variety of research models. She said too many people focus on blaming an individual for their struggles with obesity, but focusing on incentivizing healthy foods is a more productive method.

“Not only are we combining different disciplines, but we are creating something new in terms of knowledge and solutions,” she said.