Updated: Dec. 3, 2018 at 10:14 a.m.

Nearly 40 percent of students are food insecure, according to a report recently obtained by The Hatchet.

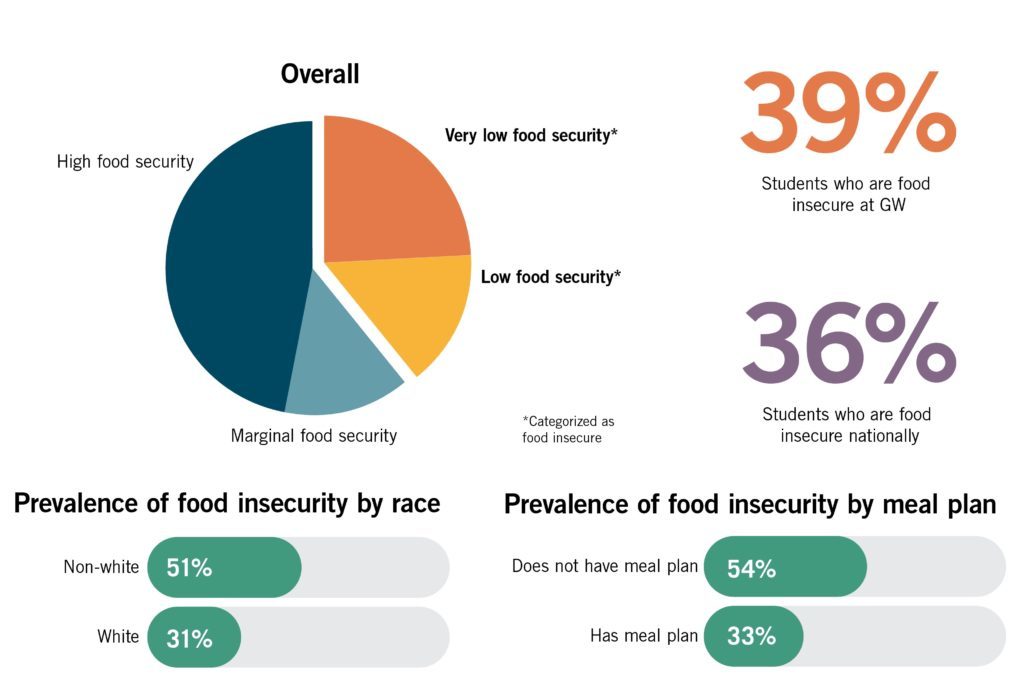

The report, released by the Wisconsin HOPE Lab in March and obtained by The Hatchet Thursday, is the first publicly documented data of food insecurity at GW. Thirty-nine percent of students reported that they faced low or very low levels of food security – meaning they have worried that they would run out of food, have cut or skipped meals because they did not have money or could not afford to eat balanced meals, among other factors.

“We’ve always operated on the assumption that food insecurity is a serious issue here at GW – this is just confirmation,” Grant Nilson, an outgoing co-director of internal affairs for The Store, the University’s student-led food pantry, said.

The level of food insecurity at GW was largely on trend with national data from 41 other surveyed universities, which reported that about 36 percent of students are food insecure on average, according to the survey. Nearly 250 students responded to the HOPE Lab survey.

The data also showed that food insecurity hits underrepresented groups the hardest. More than half of non-white students participating in the survey were classified as food insecure, compared to 31 percent of white students. About 54 percent of Pell Grant recipients also fell into the category.

[gwh_image id=”1073886″ credit=”Emily Recko | Graphics Editor” align=”right” size=”embedded-img”]Source: Wisconsin HOPE Lab[/gwh_image]

Students who lived off campus or did not have a meal plan also experienced food insecurity at higher rates than their peers. About 53 percent of students who did not have on-campus housing or a meal plan were classified as food insecure.

Food insecurity has been an increasingly prevalent topic at GW for years after the 2016 opening of The Store. In spring 2018, more than 850 students had signed up to utilize the pantry, student leaders said.

Students have also long criticized the University’s dining plan for exacerbating the issue after officials shut down Foggy Bottom’s only dining hall in 2016 in favor of an “open” dining plan allowing students to use their GWorld funds at any participating vendor. A year into the program, students said that running out of dining cash was the norm – and officials overhauled the system in the spring to allocate dining dollars based on whether a student has an in-unit kitchen.

Student leaders from The Store, who originally obtained the report last week, said the findings highlighted the need to institutionally and adequately address food insecurity on campus.

Since The Store launched two years ago, student leaders said they have heard anecdotal evidence of students struggling to pay for meals, but they never had concrete data to support the claims until now.

Ben Yoxall, The Store’s outgoing treasurer, said members of the group are calling on officials to conduct a comprehensive survey to gauge what factors contribute to food insecurity and how different student groups are affected by the phenomena.

“We know a rough estimate of people at GW are food insecure, but we really don’t know why, we really don’t have confirmation of these numbers,” he said. “We really want to know more information.”

Saru Duckworth, the outgoing president of The Store, said the data enables members of the organization to “build a case” for officials to construct a long-term plan to address food insecurity as a systemic issue. Student leaders formed a task force last month comprised of officials, student leaders, staff and faculty to research the prevalence of food insecurity and identify ways to combat it.

“Even if the number was much lower, it matters that even one person is experiencing very low levels of food security,” she said. “It matters to all of us.”

Duckworth said the report also helps to inform the ways The Store could accommodate groups who are most affected by food insecurity, like minority and off-campus students. Duckworth said she wants the task force to discuss the feasibility of providing “culturally appropriate” foods in The Store.

Colette Coleman, the interim associate dean of students, said officials have heard concerns from students about food insecurity and are working with students “on multiple fronts” to aid students affected by the issue.

She said officials made “significant changes” to the dining plan in recent months by increasing the amount of money loaded onto students’ GWorld cards and adding an all-you-can-eat option in Pelham Commons on the Mount Vernon Campus.

She said officials have also created programs to alleviate food insecurity that are geared toward first-generation students, including the Center for Student Engagement’s monthly dinner, workshops about eating on a budget and pop-up events offering food. Officials also train academic advisers to inform students about The Store, she said.

“It is our hope that none of our students will have to live with food insecurity, but we recognize that some do,” Coleman said in an email. “Regardless of whether they are graduate or undergraduate students, we are working to address issues like food insecurity and financial need that can come between a student and their ability to succeed academically.”

She declined to say how officials reacted to the HOPE Lab’s findings and how they used the findings from the survey.

Affordability experts said the percentage of students who are food insecure mirrors a nationwide issue indicating that administrators must explore long-term solutions to ensure that students don’t go hungry.

Bianca vanHeydoorn, the director of community engagement and research application at the Hope Center for College, Community and Justice at Temple University, said the percentage of food insecure students at GW falls in line with national trends. At Temple, about 35 percent of students have low or very low levels of food insecurity, she said.

She said the data helps shed light on a nationwide problem that affects students’ ability to learn and thrive in the classroom. vanHeydoorn said colleges miss out on “the full richness” of what students have to offer when they are suffering from stress resulting from food or housing insecurity.

“It shows us the reality of what the new – or as we call it, the real – college student looks like,” she said. “The rising cost of education, the rising cost of housing, the rising cost of food all contribute to a student body that can’t access or doesn’t have their basic needs met.”

Celeste Davis, a lecturer of health studies at American University, said that in addition to food insecurity rising on campus as housing costs and tuition increase, the University could also be admitting more low-income students without helping those students adjust to the relatively high costs of dining.

She said that while schools could start food pantries to alleviate food insecurity, officials also need to think about “systematic ways” to help students, like increasing the financial aid pool or promoting food stamp programs.

“As we increase access and diversify who is coming to what school, we also have to think about who has the ability to afford to live while they’re in school,” she said. “I don’t think we take in that economic factor – yes, we’re increasing access to schools, but what does access really mean if kids are still hungry?”

Kelly Hooper and Kateryna Stepanenko contributed reporting.

This post was updated to reflect the following correction:

A previous version of this post misattributed a quote from Grant Nilson. It is now properly attributed. We regret this error.