The proportion of white students in the undergraduate student body has fallen annually for at least nine years, putting the population on track to fall below 50 percent white for the first time next fall.

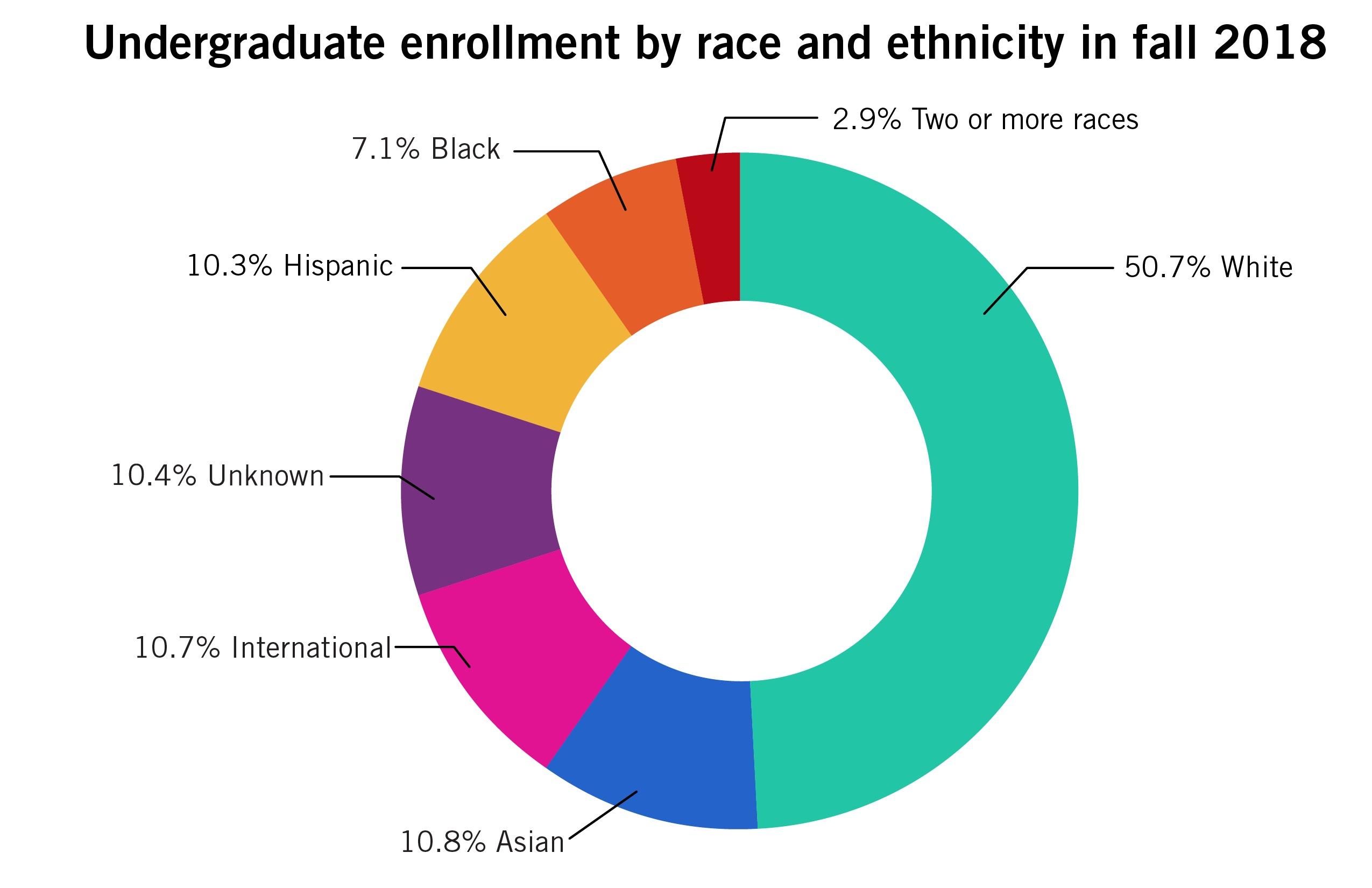

The percentage of white undergraduates fell this fall from 52.5 to 50.7, while the percentage of students in nearly every minority demographic incremented by less than 1 percent each. Since 2013, the proportion of white students has dropped by about two percentage points each year, making the fall 2018 student body the most diverse group of undergraduates ever to enroll at GW, according to institutional data.

Officials and diversity experts said the trend is likely the result of the University going test-optional three years ago and making an effort to recruit students from underserved populations.

“Graduating an academically talented and diverse student body is critical to our success as a university and enhances the educational experience for all students,” Laurie Koehler, the senior vice provost of enrollment and the student experience, said in an email.

Tina Tran | Staff Designer

Source: Institutional data

The University’s white undergraduate population has shifted between 50 and 60 percent for at least 10 years, with a high of 60.3 percent in 2013 and an overall average of 56.2 percent. But the percentage of students in every other demographic, like black, Hispanic, Asian and international students, has rarely surpassed 10 percent, according to institutional data.

This academic year, 10.8 percent of students identify as Asian, 7.1 percent identify as black, 10.3 percent identify as Hispanic and 10.7 percent of undergraduates are international students, an uptick in nearly every population compared to last academic year.

The percentage of students who identify with two or more races and students with an unknown race stand at 2.9 and 6.8 percent, respectively.

Half of GW’s 12 peer schools, including Syracuse and Tulane universities, have an undergraduate population that is more than half white, and the six other schools, like the University of Miami and New York University, stand below 50 percent, according to each school’s respective institutional data pages.

Changing admissions practices

Experts in diversity and higher education said GW may have become more diverse after switching admissions practices and recruitment strategies.

The University went test-optional in 2015 after former University President Steven Knapp made accessibility for minority students a priority of his administration. Since the switch, officials have seen record-high applicant numbers with an increase in applications from Latino, black and first-generation students.

Susan Albertine, a senior scholar in the Office of Quality, Curriculum and Assessment in the Association of American Colleges and Universities, said when students start to see that GW is welcoming of all racial and ethnic populations, individuals from minority backgrounds might be more inclined to apply knowing that they have a better chance of acceptance.

The University’s admit rate has also risen for the past two years, climbing to nearly 42 percent last spring.

“If the buzz is GW is a good place for diverse students, more diverse students start to apply, so there could be an effect over time,” Albertine said.

Still, GW and many of its peer institutions lag behind the national proportion of minority college-age students.

Nick Daily, the assistant dean for the Office of Black Student Affairs at the Claremont Colleges, said if officials continue to recruit minority students using programs like international student scholarships and outreach to students at D.C. schools, high school students will be more confident telling peers that GW is within their reach.

“You do want institutions that are articulating their commitment to diverse populations of students, and you want to make sure that in that articulation, it’s not just a numerical articulation,” Daily said.

Meeting ‘changing demographics’

Koehler, the senior vice provost of enrollment and the student experience, said enrolling a diverse student body ensures officials are meeting the “changing demographics of higher education market” and promoting cultural understanding among students.

“Graduating a class that is diverse and academically successful is critical for achieving our aspiration of pre-eminence, for the institution’s long-term viability and for ensuring that our alumni thrive in their post-graduation careers,” Koehler said.

She said officials have brainstormed ways to reach a broader range of student populations with recruitment trips that target communities in the South, Southwest and West that officials “may have been less intentional about reaching in the past.” She said officials also partnered with schools and organizations like YES Prep charter schools in Texas and “Say Yes to Education” in North Carolina and New York, two organizations that serve underrepresented communities.

Since GW switched to a test-optional admissions policy in 2015, she said the University’s applicant pool has also become more diverse with an uptick in applications from first-generation students.

“While we are pleased that diversity and academic quality continue to rise, we know that what matters more than who enrolls is that students who enroll graduate and have a positive experience while at GW,” Koehler said.

Aiding student groups

But as officials continue to ramp up diversity efforts, experts said the University needs to tailor its academic programs and career services to the differing needs of student groups, like individualized tutoring or mentorships.

Daily, the assistant dean for the Office of Black Student Affairs at the Claremont Colleges, said officials can help recruit and retain students from different demographics by ensuring faculty are representative of all populations because “students frequently go to the people who look like them.”

He said officials should also routinely survey administrators and students with campus climate surveys and offer cultural competency trainings to staff to ensure the University is aware of the needs of an increasingly diverse student body.

“The diversification of those domains – how are we making sure that those people are persisting and being retained?” he said.

Albert Camarillo, a professor of public service and history at Stanford University, said when students are educated in an environment with a diverse student body, they are better prepared to be “successful citizens” of the world and country because they are exposed to different cultures and experiences.

But he said institutions also need to enhance their programs for groups like international students, who may need more individual guidance in finding a career after graduation than domestic students. He said first-generation students could also benefit from individualized guidance because they don’t have parents who can help them navigate through college.

Students began a first-generation mentorship club in 2015 and the University dedicated the eighth floor of Thurston Hall to house first-generation students this year.

“If you throw a diverse student body together and just think they will get along, you’re wrong,” he said. “An institution, whether it’s a university or the United States military, any other institutions have to figure ways to help to facilitate interactions, discourses across and between groups.”