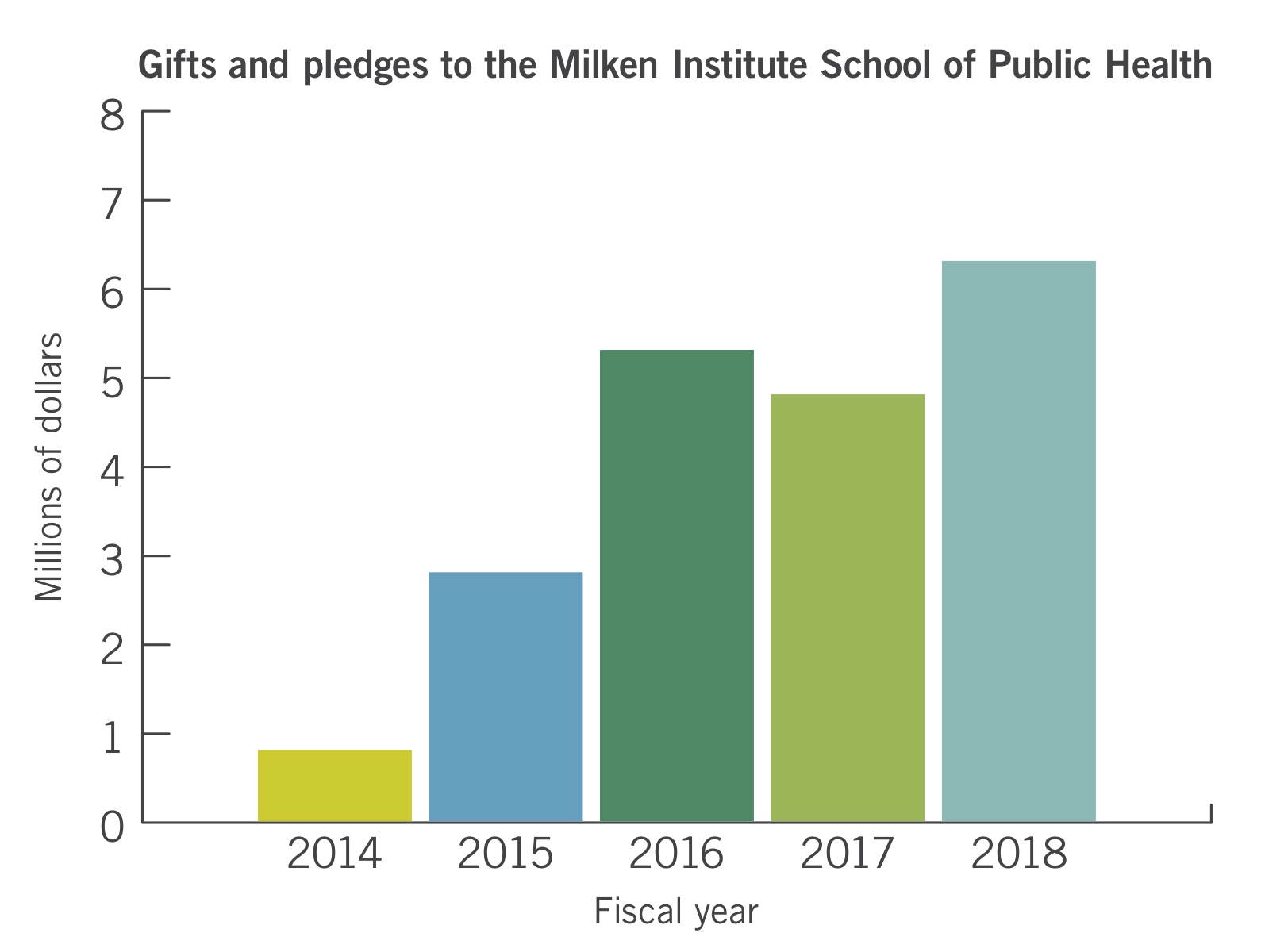

The public health school received more than $6 million in gifts and pledges in 2018 – the highest amount in at least the past five years.

The Milken Institute School of Public Health received $800,000 in gifts and pledges in 2014, but last fiscal year that number jumped to $6.3 million – a nearly sevenfold increase, according to the school’s annual financial progress report issued this fall, a copy of which was reviewed by The Hatchet. Fundraising experts said the school’s ability to increase the amount of gifts and pledges, which include donations from alumni, faculty and families, will help boost the public health school’s national reputation, bringing in more money for facilities, events, research, and student and faculty support.

Gifts, which are a one-time donation, and pledges, which are recurring donations, comprised 1 percent of the public health school’s revenue in 2014 and 3.5 percent in 2018. The school hit a high point in 2016 when gifts and pledges comprised 5.3 percent of the school’s revenue.

Emily Recko | Graphics Editor

Source: Milken Institute School of Public Health annual financial report

Milken’s annual financial report splits its revenue into six categories: indirect research, direct research, tuition and fees, gifts and pledges, endowments and other revenue. In fiscal year 2018, tuition and fees comprised most of the school’s revenue at 44.9 percent, while direct research came in at No. 2 with 44.1 percent.

Public health school spokeswoman Mina Radman declined to say why the amount of gifts and pledges given to Milken has increased over the past five years and what the money will go toward.

She declined to say how many individual donors gave to the school and what the biggest gift was in 2018 and 2017. She also declined to say how Milken encourages donations each fiscal year.

Radman said she could not respond to The Hatchet because the school recently hired a new vice president of development who “is getting up to speed.”

Fundraising experts said Milken’s nearly 700 percent uptick in the amount of gifts and pledges helps the school boost its research efforts and enrollment, and improve the quality of its faculty. They said the increase also shows that public health officials are improving engagement with donors.

Abbie von Schlegell, a consultant who specializes in fundraising and runs the consulting firm A. von Schlegell & Co., said gifts come in the form of checks or stocks, which she said a university can sell, and pledges typically last for five years.

“A pledge of cash to an institution, any institution, doesn’t matter which kind, is a feel-good sentiment,” she said.

Jessica Browning, the senior vice president of the Winkler Group, a fundraising firm that works with nonprofit organizations, said increasing the number of donors who promise to pay a specific amount over time means that the school is likely working successfully with alumni to encourage donations.

In recent years, the University has worked to boost its historically low alumni giving rate. Officials in the development office announced in September that individual schools’ development offices will use monthly reports to update deans on fundraising progress.

“In fundraising, we like to say it’s all about the fundamentals,” Browning said. “It’s connecting people with a philanthropic gift with their desire, with the mission, with the vision of an organization and really just talking with them, introducing them to the project, getting them excited about the possibilities.”

Browning said the donations and pledges keep the school afloat – supporting research, facilities, faculty and student services – while also building the school’s stature among alumni.

“I think universities are propelled by gifts and donations, especially as tuition can only cover so much,” Browning said. “It’s really the philanthropic dollars that propel an institution forward.”

Richard Ammons, a senior consultant and principal at Marts & Lundy, a fundraising firm that raises money for universities, said the increase in gifts indicates that the school’s development office is showing donors that “they can impact the quality of life, the quality of education that goes on by making increasing philanthropic gifts.”

He said the additional money could fund faculty’s research endeavors, which could build the school’s reputation nationally.

Milken has boosted research efforts and received large national grants in recent years, like a $7 million grant in 2016 for researchers to study the microbiome and a $4 million grant last year to study anemia in India. The school also made national headlines earlier this year for conducting a review of death records in Puerto Rico in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria.

Research grants are considered a separate category and are not included in gifts and pledges in the annual financial report.

“Schools that have faculty members who are doing research and writing in the field, that gets the attention of practitioners and therefore increases the body of knowledge around that particular subject, help to attract increasing philanthropic support,” he said.