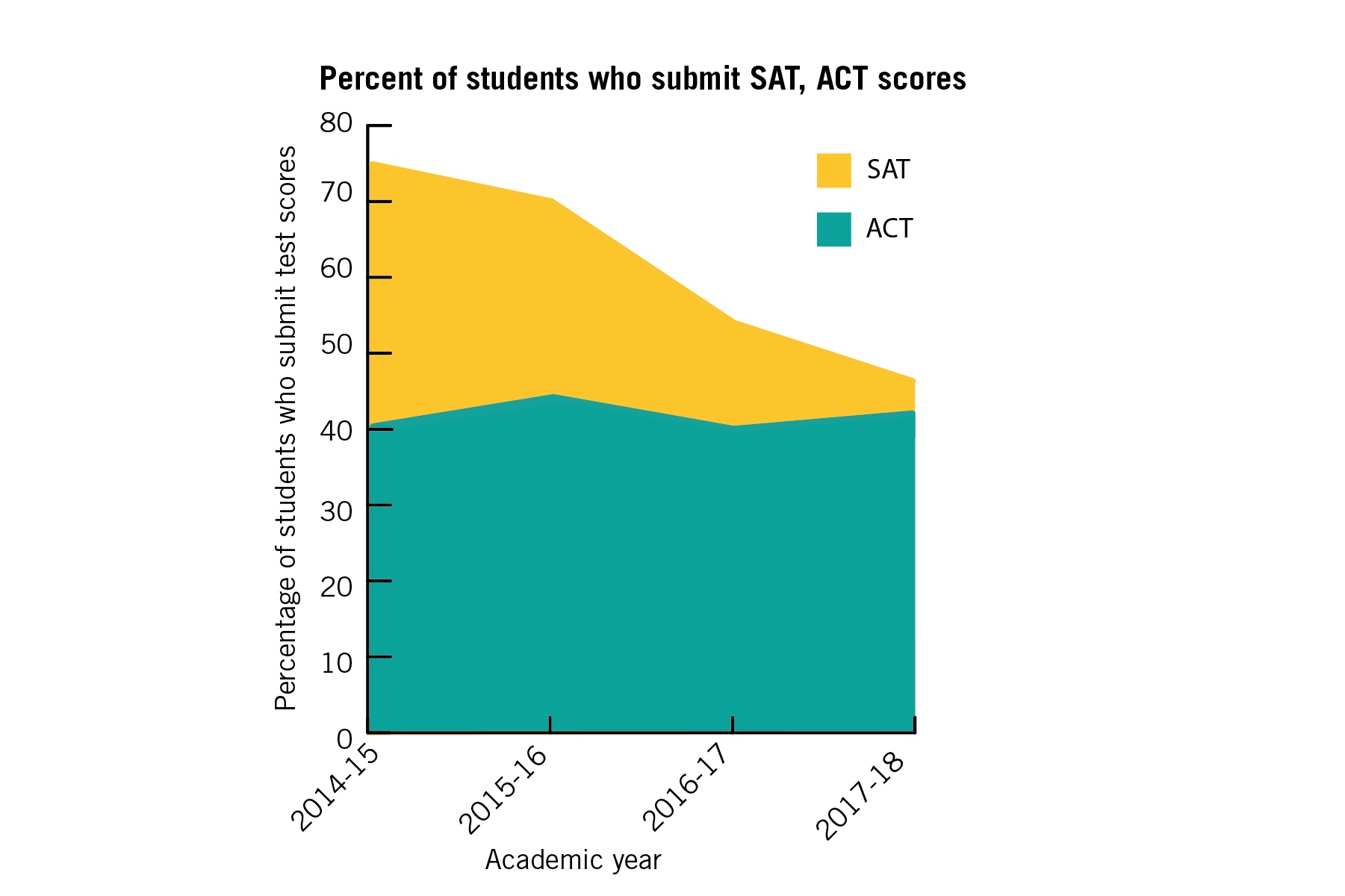

In line with a nationwide trend, the percentage of students sending in their SAT scores has dropped by more than a third since the University went test-optional three years ago.

While the percentage of students submitting ACT scores has been largely stable over the past three years, the percentage of students submitting their SAT scores fell from 70 to 46 percent, according to institutional data. On top of the test-optional switch, officials attributed the drop to nationwide changes in standardized testing, like the rising popularity of ACT scores and an overhaul of the SAT’s score calculations in 2016.

Laurie Koehler, the senior vice provost of enrollment and the student experience, said officials anticipated a decline in the number of students submitting standardized test scores when GW initially went test-optional in 2015. But while the percentage of students who have submitted SAT scores has plummeted, the percentage of students submitting ACT scores has remained relatively the same, hovering at about 42 percent over the past three years, according to institutional data.

Jack Liu | Hatchet Designer

Source: Institutional data

Koehler said the SAT’s swap from a 2,400- to 1,600-point scale and changes in the “content and approach” of the test also contributed to a decline in the percentage of students submitting their scores. Koehler said in discussions, high school counselors, students and parents were “concerned” about the impact of the changes.

“These national trends, combined with GW’s announcement in July 2015 to adopt a test-optional approach to admission beginning with the class that would enroll in fall 2016, have contributed to changes in test submission patterns at GW,” she said in an email.

Forty-seven other institutions also went test-optional the same year as GW, including schools like Brandeis University and Ithaca College, according to the National Center for Fair and Open Testing. Over the same time period as GW, the percentage of students submitting SAT scores at Brandeis and Ithaca also dropped from 62 to 44 percent and about 55 to 51 percent, respectively, according to institutional data at each school.

Wake Forest University is GW’s only peer school that is also test-optional, while New York University and the University of Rochester both have iterations of the policy, where applicants can choose to instead send in scores for different exams, like SAT subject or Advanced Placement exams.

Admissions and higher education experts said the percentage of students choosing not to submit SAT scores will continue to fall as students realize that officials do not perceive students who choose not to submit scores in a negative light.

Michael Walsh, the dean of admissions at James Madison University, said that since the school went test-optional last fall, the percentage of students submitting their SAT scores also fell from 22 to roughly 18 percent.

Walsh said JMU became test-optional because officials noticed that almost half of incomplete applications were the result of missing test scores, which he attributed to economic disparities among students. Once students adjust to college during their first year at JMU, there is no difference in GPA averages for students who come from different economic backgrounds, he said.

Data presented to the Faculty Senate in March showed that students who choose not to submit their test scores to GW have about the same first-year GPA as those who submit their scores, despite initial fears from faculty and experts about an academic disparity between students.

“Now that people have seen that we are admitting students who didn’t send in their test scores and didn’t hold it against them, we were just straightforward, I expect to see that number grow a little bit,” Walsh said.

Steven Stemler, an associate professor of psychology who specializes in education at Wesleyan University – a school that went test-optional in 2014 – said SAT scores have historically been considered to predict a student’s GPA during their freshman year, but since schools have gone test-optional, admissions officers place less emphasis on the scores.

Since Wesleyan went test-optional in 2014, the percentage of students submitting SAT scores at Wesleyan also decreased from 77 to 49 percent in 2017.

“If we hang our hat on just GPA as a measure of success, we’re missing the broad range of outcomes that schools themselves say they want to achieve,” Stemler said.