About 1,500 graduate and undergraduate students are currently registered with Disability Support Services – a roughly 36 percent jump from the year before.

The number of students registered with the disabilities office has surged over the past several years, which experts attributed to more students feeling comfortable seeking accommodations. Among undergraduates, 6 percent of the student population registered with the office in 2017 – the highest in at least nine years, according to federal data.

For seven years, GW reported that fewer than 3 percent of its students registered with DSS. Before that, the University hadn’t registered more than 3 percent of students with disabilities since 2009, when it reported registering 5 percent of the undergraduate population.

The National Center for Education Statistics does not provide specific data for schools that register fewer than 3 percent of undergraduates.

Susan McMenamin, the director of DSS, said the percentage of undergraduate and graduate students who registered with the center has risen by about 50 percent over the past five years and increased by more than 100 percent for students registered with a chronic or mental health condition over the same period.

DSS offers accommodations like note taking assistance, special technology labs in Gelman Library and test-proctoring services. Students registered with DSS must submit a form documenting their disability and notify professors about their disability in a letter on the DSS website.

Emily Recko | Graphics Editor

Source: National Center for Education Statistics

“Because of our commitment to serving our students and since students and their families are becoming more familiar with the services that are available to them as students continue their studies at the collegiate level, we are seeing an increase in requests for assistance,” McMenamin said.

Not every student with a disability needs to register with DSS if they don’t require accommodations “to maintain active, ongoing participation in their academic program,” she said.

“DSS is committed to ensuring full and equivalent participation for persons with disabilities in the GW community by providing essential accommodations for housing and for academic participation,” McMenamin said in an email.

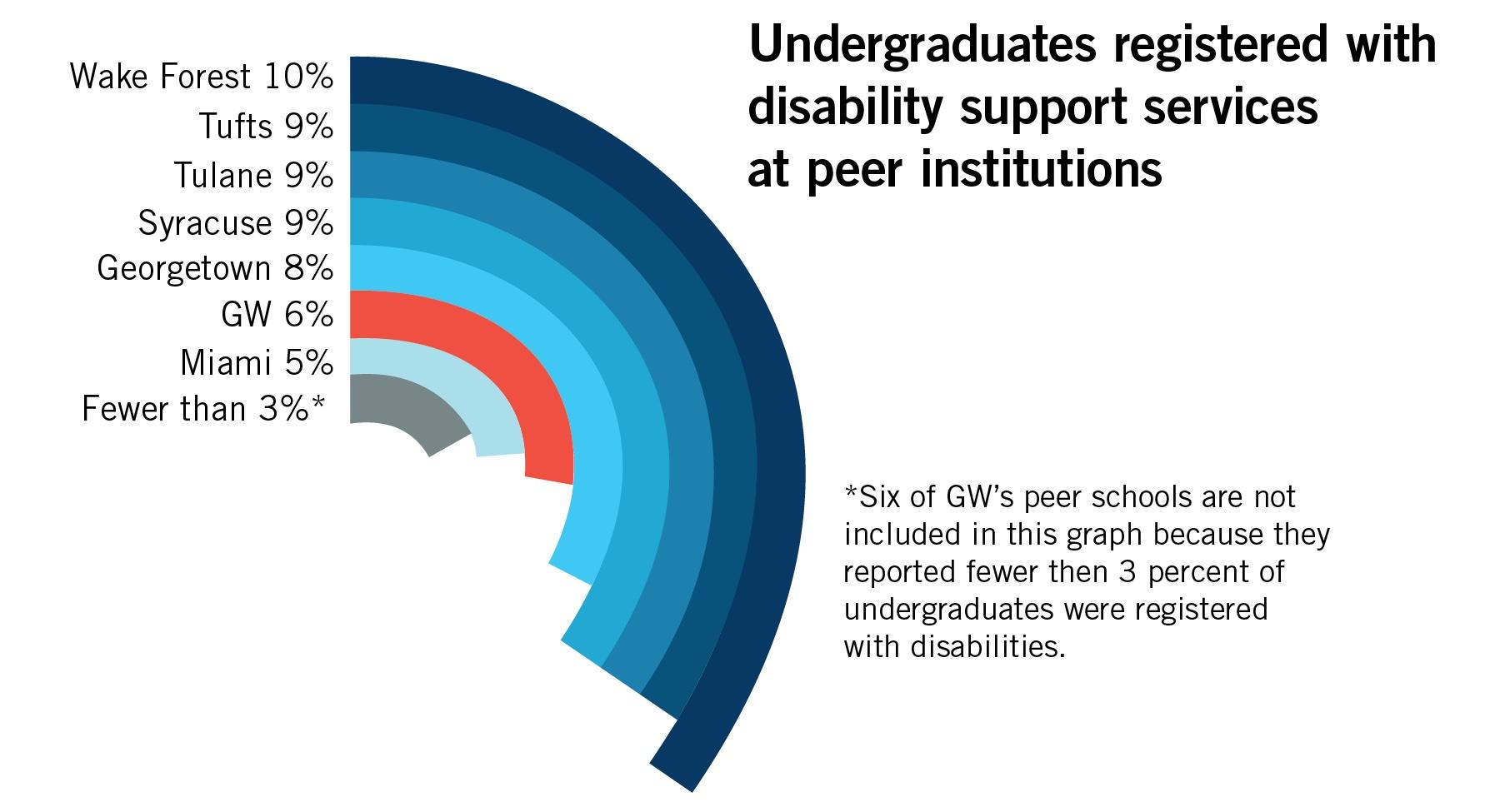

Before last academic year, fewer than 3 percent of undergraduates registered with DSS – behind the percentages logged by at least seven of GW’s peer institutions, like Georgetown and Tufts universities. The University was among six of its 12 peer institutions that registered fewer than 3 percent of undergraduates with a registered disability in 2016.

Wake Forest University has the highest percentage of students with a registered disability, registering 10 percent of undergraduates in 2017.

The University fell under investigation for possible discrimination against students with disabilities last academic year – the same year that the percentage of students with disabilities jumped. The Office for Civil Rights found that the University lacked proper formatting and captions for students on GW webpages.

Officials resolved to develop a plan that would improve online accessibility on University websites after the probe closed in March.

Higher education experts said the sudden rise mirrors a nationwide shift toward students feeling more comfortable telling others about their disabilities, especially for those with mental health conditions like anxiety or depression.

Patrick Randolph, the director of the center for student accessibility at Tulane University, said the jump could represent a shift in students’ perceptions of their disabilities. Students often highlight their disability as “a badge of courage” when applying to school – using it as a way to show they can excel at a competitive university, he said.

About 9 percent of students registered with a disability at Tulane last academic year – down from 11 percent the previous year, according to federal data.

“They’re being better supported in high school and earlier so they’re able to matriculate to college more successfully,” Randolph said. “More and more students are starting to embrace their diversity in general and because of that, it’s not as stigmatizing as it once was.”

Rory Stein, the assistant dean of students with disabilities at Boston College, said that officials could be more conscious of ensuring that students with disabilities have the resources they need because they are more likely to withdraw from a school than other students.

By promoting mental health services and offering more academic accommodations, students with a registered disability could feel more inclined to stay at a school because their needs are met, he said.

“These withdrawals could be prevented with some education and outreach about these services and what we can offer them to ameliorate the accommodations of their condition,” he said.