Updated: Aug. 28, 2018 at 4:39 p.m.

The closure of a federal Title IX investigation could mean a series of policy changes for GW’s disciplinary offices – on top of a two-month-old overhaul of the University’s Title IX procedures, experts said.

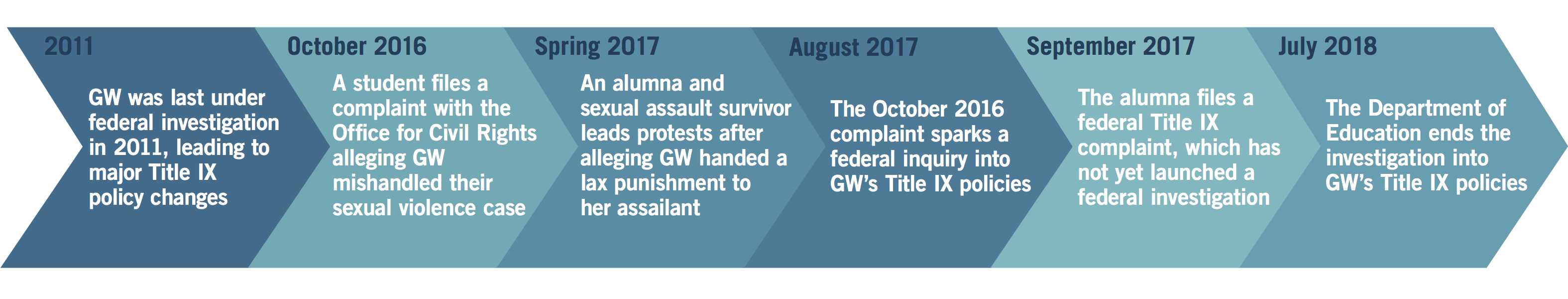

University spokeswoman Maralee Csellar said the federal probe – which began last August after a student alleged that the University mishandled their sexual violence case – concluded July 25 after officials reached a mutual agreement with the Office for Civil Rights. She said the agreement, which was not immediately available to the public, was reached through OCR’s facilitated resolution process – giving the University means to close the investigation quickly amid increased scrutiny of its Title IX policies.

“GW welcomes comments from all members of the community about the University’s ongoing work on Title IX programs and services as it implements the new policy,” Csellar said in an email.

She declined to comment on the specifics of the complaint and the mutual agreement “out of respect for the individuals involved.”

Title IX experts said mutual agreement result in a catalog of recommendations that could improve the University’s Title IX policies, remedying what the complaint faults within the office.

Emily Recko | Graphics Editor

The recommendations approved in the mutual agreement could tack onto several major changes to the Title IX office implemented July 1 following the conclusion of an external review of the way GW handles complaints of sexual misconduct. The new policies included a move from a hearing board to a single investigator for Title IX investigations and a mandate that all faculty must report incidents of sexual misconduct to the Title IX office.

Alan Sash, a partner in the litigation department at the firm McLaughlin & Stern, who has worked on Title IX cases, said the mutual agreement likely includes recommendations to remove “barriers” to reporting, which could mean the implementation of new policies like training and educational programs for students and faculty.

“Universities do not have much control over when the investigation is closed,” Sash said in an email. “They must comply with the investigatory process and wait for a decision.”

Marissa Pollick, a sport management lecturer at the University of Michigan with experience in Title IX research, said a voluntary agreement is often pursued by a university as a means to protect its image because schools don’t have to admit that they are “responsible or liable.”

“It protects them in the future because they don’t want to admit that they violated anything,” she said.

The University fell under scrutiny after an alumna led a series of protests and petitions after she felt administrators mishandled her Title IX case. The high-profile demonstrations were followed by officials publicly addressing student concerns with its Title IX office and hiring an external law firm to review its policies.

Pollick added that the resolution agreement the University signed last month is probably similar to the agreement reached between GW and OCR in 2011, when the Department of Education last investigated GW’s Title IX policies. The last resolution agreement forced the University to enact a series of Title IX policy changes, including listing sexual assault as a separate offense within the student code of conduct.

Dan Schorr, the managing director at Kroll Associates, a corporate investigations and risk consulting firm, said a complainant can appeal the outcome of a federal investigation or file a civil suit in court if they see that officials aren’t complying with the terms of a mutual agreement. He said legal action is “always an option.”

“That’s not precluded by the fact that OCR’s done an investigation,” Schorr said.

Experts said GW is not out of hot water after the closure of the federal investigation because under the Trump administration – where Title IX complaints are reviewed on a case-by-case basis – several complaints are likely to arise over at least the next two years.

Under former President Barack Obama, individual complaints launched large-scale investigations of a school’s Title IX procedures, while President Donald Trump’s administration evaluates whether there has been a violation only on the basis of a specific incident.

Carly Mee, the interim executive director for SurvJustice, a nonprofit organization offering legal assistance to survivors of sexual violence, said Trump-era Title IX investigations could mean a school might face complaints more often, as widespread, systemic issues go uncorrected.

The same alumna who launched high-profile on-campus demonstrations last year to protest the outcome of her Title IX hearing filed a federal Title IX complaint last fall. The complaint has not yet launched a federal inquiry.

“It does put the burden on students to keep filing complaints, like complaint after complaint, instead to show that this is a common practice instead of OCR working on its own to investigate whether there’s a pattern,” Mee said. “It could be resolved in a different way that’s not going to help as many people who report in the future.”

Editor’s note: This post was updated to clarify a paraphrase from Dan Schorr.