For the first time in at least nine years, none of the prospective students on the waitlist for the Class of 2022 will receive an acceptance letter from GW.

Emily Recko | Graphics Editor

Source: Institutional research

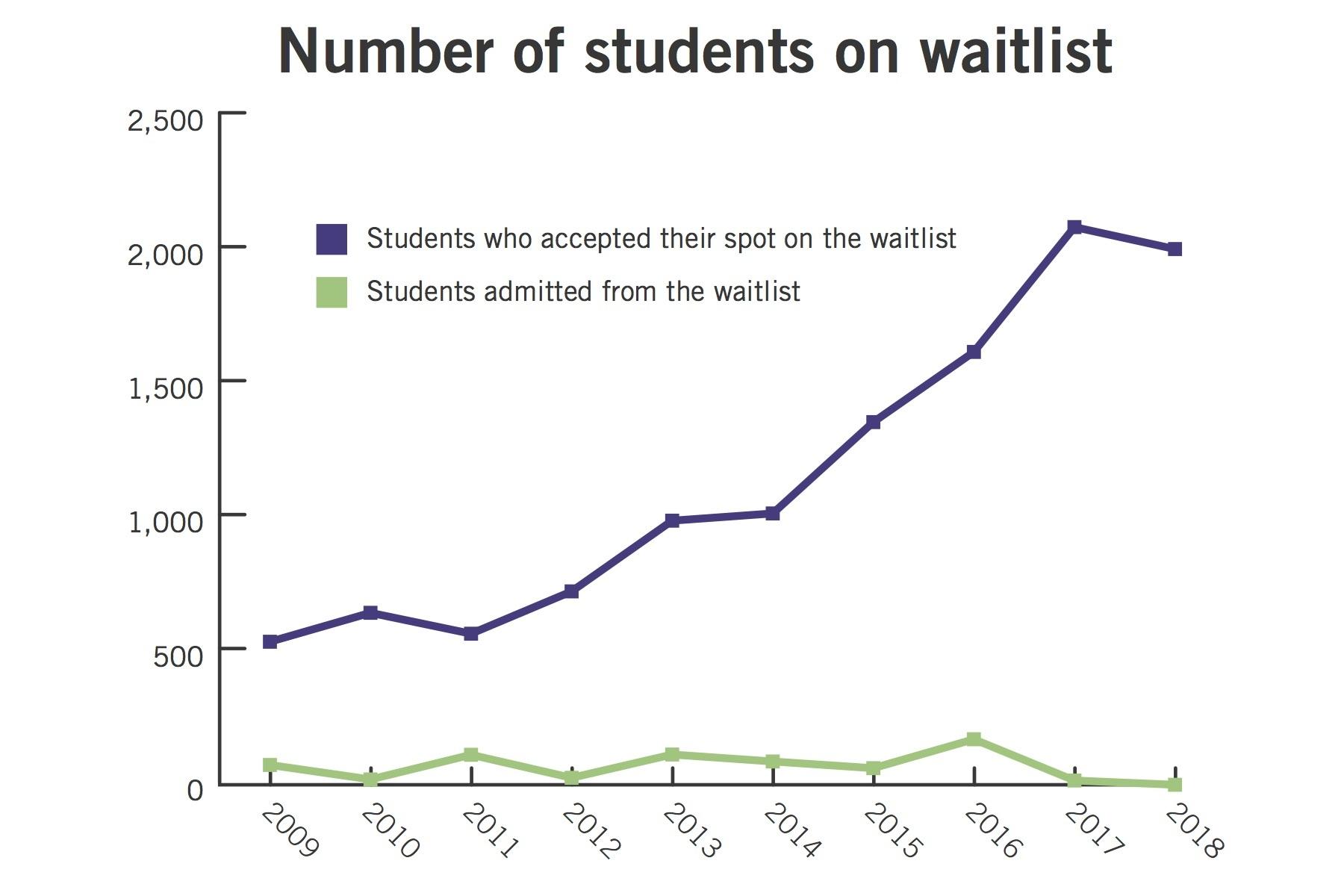

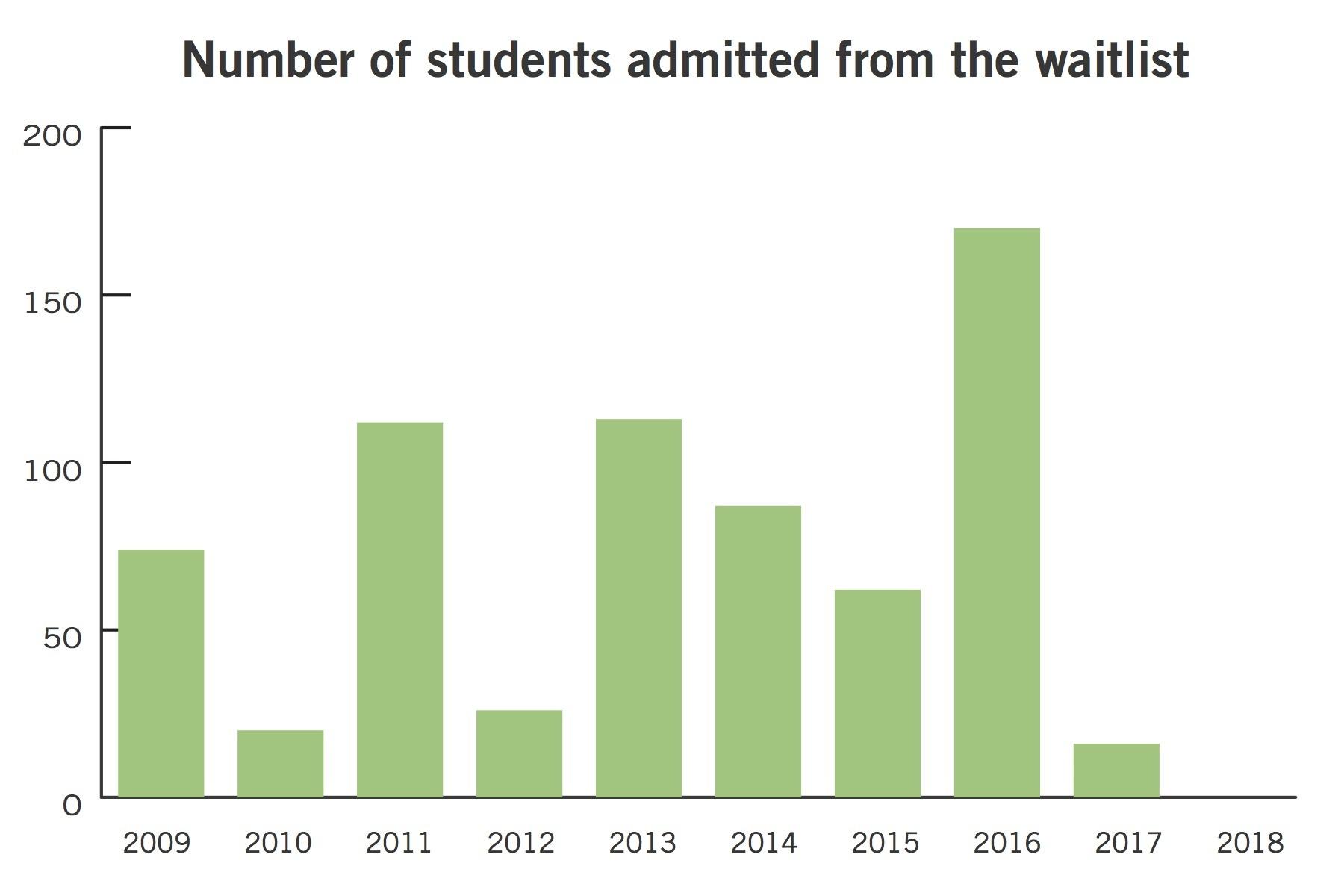

Dean of Admission Costas Solomou announced to waitlisted students May 1 that after receiving nearly 27,000 applications for the incoming freshman class, GW hit its capacity and does not “anticipate admitting anyone from the waitlist this year,” according to an email obtained by The Hatchet. The University admitted an average of 76 students from its waitlist between 2009 and 2017 – with a high of 170 students in 2016 and a low of 16 the next year – according to institutional research.

Solomou said about 2,000 students accepted a spot on GW’s waitlist this year in addition to the roughly 11,000 students admitted to the Class of 2022.

He said being waitlisted could cause “anxiety and stress” for students trying to solidify their college plans.

“We were happy to make a quick decision about closing this year’s waitlist to avoid keeping those students in limbo any longer than necessary,” Solomou said in an email.

While officials did not say how many students were offered a waitlist spot for the Class of 2022, the University offered roughly 5,600 students a spot on the waitlist last year, according to institutional research. About 2,100 students took up the offer for a spot on the waitlist, but just 16 students were accepted to GW.

Solomou declined to say if officials anticipated that students wouldn’t be accepted off the waitlist this year and if officials have any plans to alter the current waitlist system.

Jamie Moddelmog, a high school senior from California who was put on the waitlist, said he was disappointed to receive a definite rejection from GW because the school was one of his top picks. But he said being waitlisted first and then rejected was easier than being denied from the start.

Moddelmog said he didn’t expect an acceptance from GW because waitlist acceptance rates across the country are typically very low, but he was surprised the University wasn’t accepting anyone from the waitlist.

“I wasn’t that hopeful, but I figured they’d at least go to the waitlist a little bit, so it was something different than I expected,” he said.

Emily Recko | Graphics Editor

Source: Institutional research

The notice comes as colleges across the country are offering a higher number of waitlist spots than the number of students they anticipate enrolling for their incoming classes, according to an Inside Higher Ed article published last month.

The University has increased the size of its waitlist from roughly 500 in 2009 to 2,100 in 2017, according to institutional research. The University typically enrolls about 2,500 students in its freshman class each year.

Brown University offered waiting list spots to about 2,700 of its applicants this year, while its freshman class size last fall only had roughly 1,700 students, according to the Inside Higher Ed article. The University of Pennsylvania’s incoming class is anticipated to be about 2,400 students, but it waitlisted about 3,500, the article read.

Admission experts said universities might waitlist a large number of students to ensure that they can fill openings throughout the summer, as some students could change their college plans at the last minute. But they said students are often unaware of the size of the waitlisted pool and don’t fully understand the minimal chance that they have of being admitted.

Cristiana Quinn, a counselor at College Admission Advisors, a company that offers high school students college application counseling, said universities typically waitlist a high number of students because it’s hard to gauge the number of accepted students that will actually enroll.

The University accepted a record-high 11,000 students in 2017, predicting fewer students would enroll as students apply to an increasing number of schools. The University had a yield rate – the number of accepted students who enroll – of roughly 23.6 percent last year, down from 24.7 percent in 2016 and 25.5 percent in 2015.

She said placing students on a waitlist could also boost students’ confidence, especially in the case that the school was likely out of reach for the student or is known for being selective.

“There’s a lot of buzz that it’s good PR,” she said. “It’s funny – for years I have heard people say, ‘well, my child almost got into X school,’ referring to them being on the waiting list, and for some reason, it actually does make people feel good about it.”

Peter Lake, the director of the Center for Excellence in Higher Education Law and Policy at Stetson University, said universities may keep waitlist numbers high to pull students of different geographical and socioeconomic backgrounds that weren’t offered acceptances during general admission.

“It reminds me a lot of drafting in the NFL, trying to get the right types of players and when free agency is on, people are popping in and out,” he said. “It takes a keen eye to create the cohort of students you want.”

Jon Reider, the director of college counseling at San Francisco University High School, said it’s typical for universities like GW to waitlist high numbers of students to protect themselves from falling beneath their anticipated class size.

But he added that waitlisted students develop a false hope of being admitted because they aren’t informed about generally low waitlist acceptance rates. He said providing information about waitlist numbers is important to clarify their chances of being admitted.

“It’s hard on the kids if the kids believe, ‘oh I’m still alive, I still have a chance,’” Reider said. “Yeah, numerically you have a chance, but go buy a lottery ticket – you have a chance. I’m very, very clear with my students – I tell them, ‘your chances are very low.’”

Sarah Roach contributed reporting.