Updated: May 1, 2018 at 12:11 p.m.

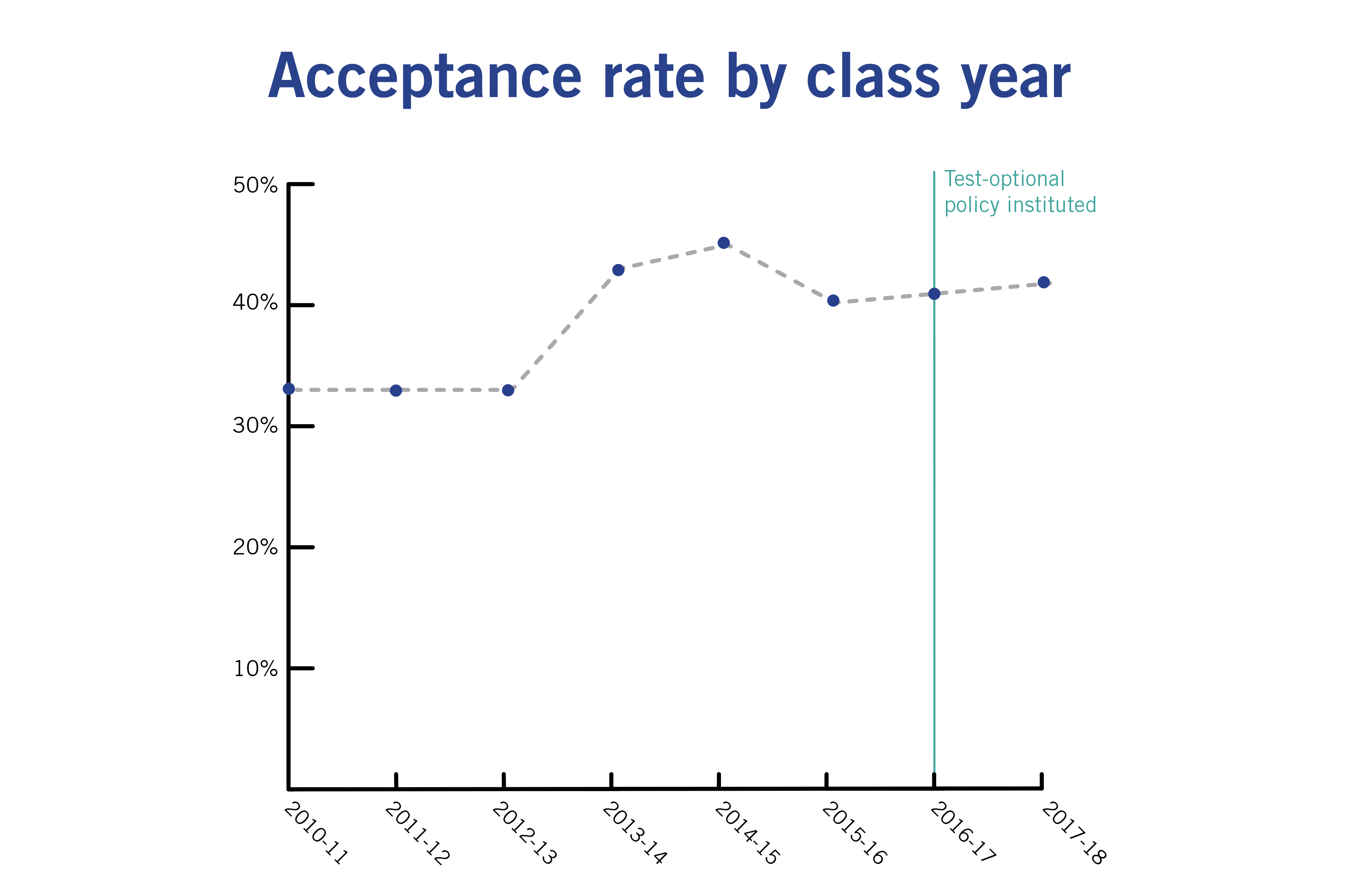

The University’s admission rate rose this year, continuing an upward trend that began three years ago.

The acceptance rate for the Class of 2022 stands at 41.8 percent – nearly one full percentage point up from last year’s 41 percent. Admissions experts said as prospective students send their applications to more schools each year, the University’s acceptance rate will rise to compensate for the decreased likelihood that students will attend – a trend seen at universities across the nation.

About 11,100 students were accepted into the Class of 2022 – roughly the same as last year when GW admitted a record number of students, Laurie Koehler, the vice provost for enrollment management and retention, said.

Emily Recko | Graphics Editor

Source: Office of Institutional Research

The acceptance rate stood at 40.2 percent in 2016. The University admitted a record 45 percent of applicants in 2015 – a slight increase from the year before – after hovering around 33 percent for three years.

Koehler said officials prioritize the quality of the students who enroll at the University over how many students are accepted – favoring candidates who would likely graduate within six years to fill the Class of 2022.

“A lot of schools may want to toot their horns about application numbers or admit rates,” she said. “It’s not that those things aren’t important, they’re indicators of something – but they’re not indicators of what, at the end of the day, we actually care about, which is who enrolls.”

For the first time this year, admissions officers used a new feature that asks prospective students to self-report grades on the Common Application and provide officials with raw writing samples that haven’t been through editing processes.

Koehler said the additional material allowed officials to “weed out” students who weren’t likely to attend GW because it required extra time to fill out the application. The feature will be evaluated throughout the summer to determine if officials will continue to require more information from next year’s applicants, she said.

“The students who did apply are more serious about GW,” she said. “If you really love a school, you’re going to do what they ask you to do to complete the application.”

Officials also hosted 21 programming events, called Inside GW Days, for admitted students to visit the University in smaller sessions than years past before deciding whether to enroll. More than 2,000 admitted students and their families visited the University as of April 27 – 14 percent more than last year’s turnout, Costas Solomou, the dean of admissions, said.

“We have to really pay attention to what the needs of our students are – our own students but also families who are trying to make a decision between GW and a list of other great schools,” he said. “I think we did it right this year.”

Solomou said admissions officers used a more “holistic” approach this application cycle that evaluates students’ raw writing samples, test grades and life experiences together instead of just high school performance or standardized test scores.

The University switched to a test-optional policy in 2015.

“Understanding some of that behavior becomes incredibly important too,” he said, “So you’re not looking at every student one-dimensionally as grades and test scores.”

Admissions experts said the increased acceptance rate demonstrates that the University is expecting fewer students to enroll because applicants are considering more universities. High school students applied to at least seven schools on average during the fall 2016 admission cycle, according to a report by the National Association for College Admission Counseling.

Paul Seegert, the admissions director at the University of Washington, said an increased acceptance rate likely means the University is recognizing that all applicants don’t have GW as their top choice. The University could bring down its acceptance rate if officials incentivized more students to send in their applications.

“If you don’t have a corresponding proportional increase in the applicant pool, then the offer rate is going to have to increase and you’re going to have to offer a higher number of applicants to get the same number of students,” he said.

David Trott, an admissions officer at the College of William and Mary, said the University might admit more students because they need to ensure they’re making enough tuition revenue from the incoming class.

The University depends on tuition dollars for about 60 percent of its total revenue to fund the University’s operating budget.

“Obviously schools are trying to be more competitive, depending on the institution,” he said. “If your admittance rate continues to go up and up and up, you’re generally perceived to be a little less competitive.”

Adam Rosenfeld, Leah Potter and Meredith Roaten contributed reporting.