Emily Recko | Hatchet Designer

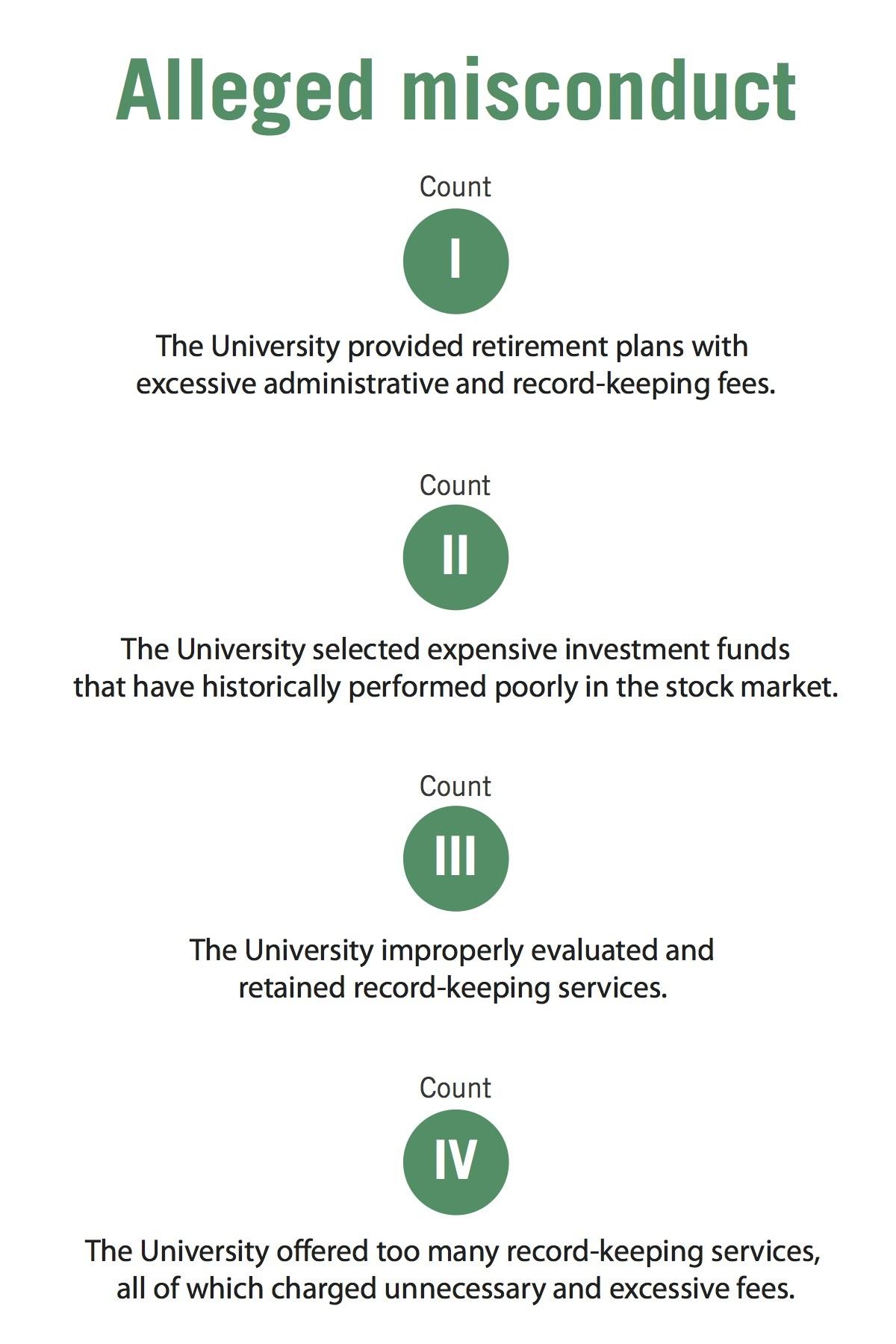

A former employee representing faculty and staff filed a class-action lawsuit earlier this month against the University for allegedly providing unnecessarily expensive retirement plans.

Former and current employees allege in a 74-page class-action complaint – filed April 13 in D.C.’s U.S. District Court – that GW breached its legal obligation to act in the best interest of its clients by offering a “dizzying array” of overpriced retirement plans that leave employees unsure of the best investment option. Experts said similar claims have been increasingly common over the past several years, and that while the plaintiff has good legal standing, parties are likely to settle out of court to avoid superfluous spending.

The plaintiffs claim GW violated the Employee Retirement Income Security Act, which compels the University to “act prudently and loyally to safeguard plan participants’ retirement dollars.” The plaintiffs request that the University reimburse its employees for retirement plan losses after the court determines the best way to calculate them.

The plaintiffs allege the University did not properly vet investment choices available for faculty and staff, which caused employees to pay higher fees than they would if they were offered plans from lower-cost fund providers. The University provides retirement plan participants with roughly 135 investment options from four companies instead of offering plans from a single provider, the suit states.

“The participants lost the potential growth their investments could have achieved had the defendants properly discharged their fiduciary duties,” the complaint states. “By selecting a single recordkeeper, plan sponsors can enhance their purchasing power and negotiate lower, transparent investment fees for participants.”

University spokeswoman Lindsay Hamilton said the case is the 18th the plaintiff’s lawyers – a series of attorneys from four separate firms – have filed against “the nation’s most prestigious universities.” She said the University intends to “vigorously defend itself in court.”

“The University provides its retirement plan participants with a very competitive retirement savings program that is administered prudently and that offers its participants an array of investment options and tools to assist in making investment choices,” Hamilton said.

Jason Rathod – an attorney at Migliaccio and Rathod LLP, one of the firms representing the plaintiffs and the only one to represent the plaintiff in court – declined to comment on the case.

Combating excessive fees

The complaint states that, despite offering lower-cost options, the University mostly offers investment options with higher administrative fees – payments that cover record-keeping costs – which has wasted millions of dollars in the past six years.

Norman Stein, a law professor at Drexel University, said administrative and investment fees are much lower than they were 10 to 15 years ago, and there is no perfect way to choose which retirement fund options to offer. But, he said there is a “strong argument” that institutions should constantly re-evaluate how costly their retirement plan fees are to avoid giving faculty and staff options that are unaffordable.

“You shouldn’t assume employees simply have the ability to sift through and figure out which of the investments have the lowest fees,” he said.

He added that the complaint highlights the need for low-priced retirement plan options because costly plans can negatively impact participants’ quality of life after retirement.

“Small differences of fees throughout a 25- or 30-year career make a tremendous difference in how much money you accumulate in retirement,” Stein said.

Tyler Anbinder, a history professor who has researched the cost of faculty benefits, said the plaintiffs claim the University should have negotiated a better deal for its retirement plan options, but that the companies mentioned, like Fidelity or AXA Equitable, are not the most expensive when compared to providers like Merrill-Lynch.

“Vanguard has super cut-rate expenses,” Anbinder said, referring to another of the University’s platforms. “The suit is kind of getting at the fact that we have these medium-priced options, that we are paying these companies a healthy amount to manage the funds and we could have shopped at something cheaper, like Vanguard.”

Abundance of plans

The plaintiffs allege in the complaint that the University provides too many retirement plan options, citing roughly 135 different funding plans offered by various companies, which cause plan participants to lose confidence in their investment decision or not invest in retirement plans at all.

“The inefficient and costly structure maintained by defendants caused plans’ participants to pay duplicative, excessive and unreasonable fees for record-keeping and administrative services,” the complaint states. “There was no prudent reason for defendants’ failure to engage in a process to reduce duplicative services and fees.”

John Banzhaf, a public interest law professor, said the University must find a middle-ground between offering too few options – which could trap employees in a plan they don’t want – and offering an abundance of plans, which could overwhelm participants.

“There’s a range and there’s a judgement,” he said. “Some people might think three or four choices is more than enough. Exactly where you draw the line is unclear.”

Stein, the Drexel University law professor, said participants in the case likely want fewer options because they don’t have enough knowledge to distinguish the best plans from hundreds of options, which can freeze people’s ability to make decisions.

“There is some academic research that says with too many choices, people make bad decisions because they are just hobbled,” he said.

A pressure to settle

Stein said similar retirement plan cases have been brought before court for years, but he has only seen an increase in cases against universities in the last two years. Within the past two months, two of GW’s peers – Georgetown and New York universities – were sued over high-priced retirement plans and bad investment options.

Duke University announced in February that it will switch from four retirement plan providers to just one in 2019, after employees sued the school in 2016 for offering too many options.

Several of the cases against universities have received class status – allowing multiple groups of people with the same injuries to together sue the same defendant – but the cases have not yet been resolved. Legal experts said GW’s case will most likely settle because class-action lawsuits can quickly become expensive.

Richard Renner, a partner in the D.C.-based employment law firm of Kalijarvi, Chuzi, Newman and Fitch, PC, said once the case is considered a class action, it becomes very expensive for the University to spend court fees to defend itself and the risk of liability is so daunting that most of these cases will settle.

“At that point, it’s actually in the University’s interest to settle because in a class-action settlement, they resolve the possibility that any other class members could bring a similar suit,” he said.

Banzhaf, the public interest law professor, said prestigious universities typically avoid going through trials concerning the mistreatment of students, faculty or staff because the cases can provide adverse publicity to the school. He said there is a tremendous financial pressure to settle to avoid huge court costs.

“This is a class-action lawsuit, and if the other side were to win a complete victory, the University could be facing huge losses,” Banzhaf said.

Lizzie Mintz contributed reporting.