Emily Recko | Staff Designer

Source: Center for Career Services

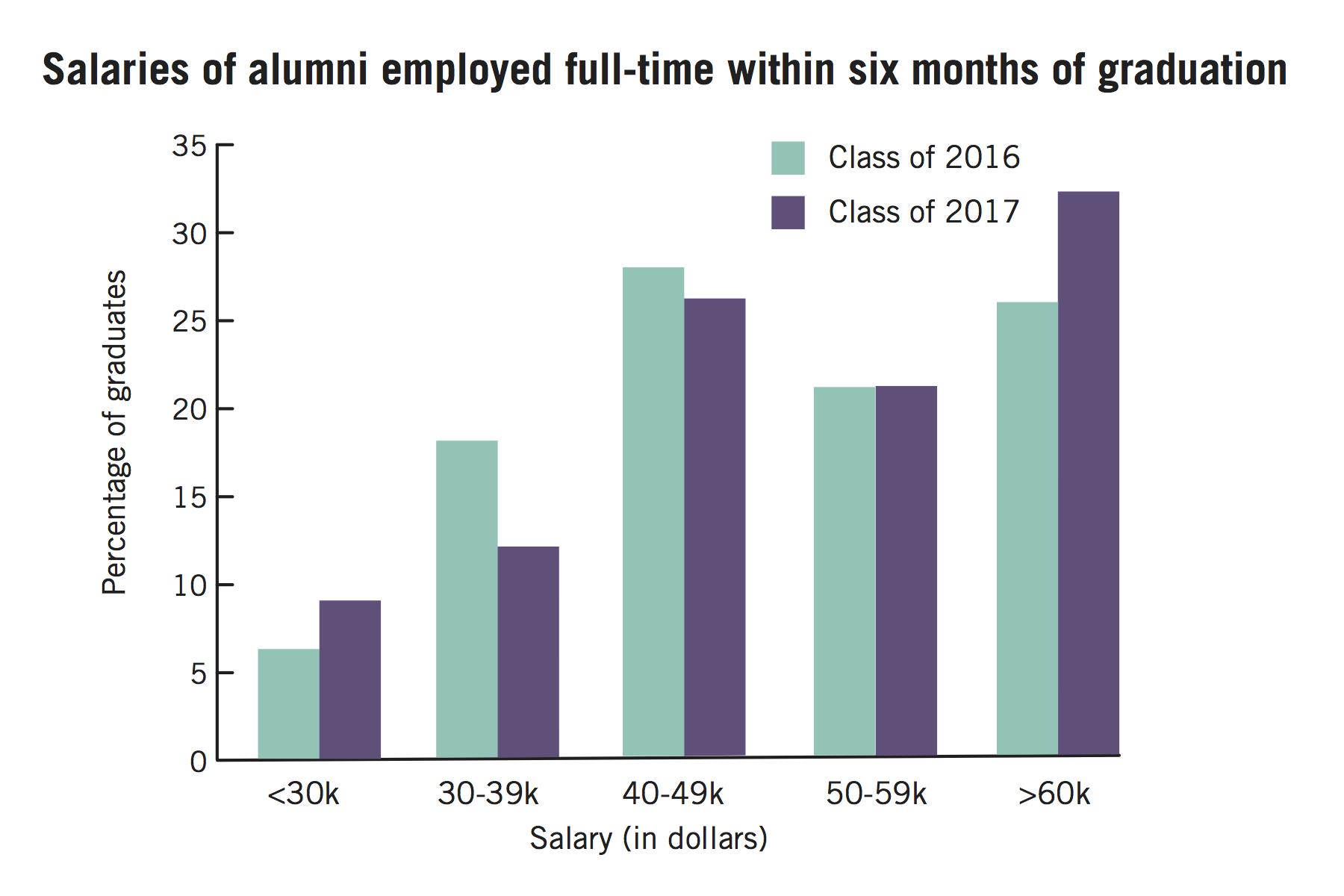

The Class of 2017 is making more money after graduation than previous classes, according to new University data.

More than 2,000 alumni participated in the University’s First Destination Survey – an annual questionnaire released earlier this month that checks in with alumni six months after graduation. The survey found that about a third of students working full-time are making more than $60,000 within a year of graduation – up from 27 percent a year ago. Experts said the increase demonstrates that students are using the career center and the University is recruiting faculty who can help students find secure jobs in their respective fields.

About 89 percent of participants in the survey reported that they were employed, continuing education or involved with other activities, like travel or community service – down two percentage points from the Class of 2016 survey results.

Rachel Brown, the assistant provost for University career services, said the results from the survey were “fairly consistent” with classes in previous years. She said the University’s consistently “high numbers” can be attributed to expanded career center initiatives over the past several years and increased outreach to the Class of 2017 through LinkedIn and faculty connections.

For the first time, the results from the Class of 2017 also included information from the National Student Clearinghouse, which maintains a database that officials can use to verify whether alumni are pursuing graduate degrees.

Brown said the ramped up outreach and added data from National Student Clearinghouse gave the University the most accurate information about post-graduate outcomes in recent years. Officials were able to verify information on 88 percent of students who graduated last year compared to 85 percent from the Class of 2016, she said.

“The success of GW graduates is a testimony to the quality of our students and the quality of the GW experience and our community,” she said in an email.

Officials have placed a heightened focus on career services in recent years, hiring more specialized career coaches and improving communication between career staff and undergraduates. The career center was the top pick for donors in 2015, and funding for the center doubled that year to hire more career coaches.

The fundraising led to new programs and a 50 percent increase in student use of the center since 2013.

Higher education experts said the new data likely reflects the commitment to expanding career services, though there wasn’t a substantial change in graduate outcomes this year. Those experts said the salary increase could also incentivize students to apply to GW, knowing they have the resources to secure a job after graduation.

Peter Lake, the director of the Center for Excellence in Higher Education Law and Policy at Stetson University in Florida, said these surveys help universities determine if they are succeeding at their goal by giving students the right tools to find work or continue their education after they leave.

Lake said the hike in students earning $60,000 or more is a “reflection of the strength” of the University’s career services, which helps students line up work from the time they start as an undergraduate. If the salary continues to increase, he said it will incentivize more students to apply to the University.

“That tells me you’re not going to have any trouble getting people to apply to the school at all and accept your offers,” Lake said. “Those are very good, very impressive numbers.”

But some experts said outliers in the data, like a few students with extremely high salaries, could drastically affect averages, and because the survey collects data over a six-month period, there could be differences between students who fill out the survey immediately after graduation or six months out.

Gary Miller, the director of career services at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, said it’s challenging to compare outcome data across several years because “it might not even be reflective of what the actual employment trend is.”

“It might just be reflective of when someone filled out the survey or some other anomaly like that,” he said.

Career centers and advising offices should make increased efforts to get underclassmen to use their services so universities can continue helping students secure opportunities after graduating, Miller said.

“Students who engage in career conversations earlier during their time in college have a little bit longer runway to make sure that they’re launching to whatever is going to be next for them,” he said. “Universities have responsibilities to help students dialogue around that and provide career education services that are going to help them.”