A group of seven public health professors are conducting a high-profile examination into the death toll in Puerto Rico from Hurricane Maria, which ravaged the island last September.

The professors, from the Milken Institute School of Public Health, will use existing records and death certificates from Sept. 20, 2017 – the day the hurricane struck – to February 2018 to reach a more precise estimate of the death count that can be attributed to the hurricane on the island. The study, which was commissioned and funded by the Puerto Rican government, has received widespread attention since it was announced last month amid controversy over how authorities managed the aftermath of the storm.

Faculty say the research team aims to release preliminary results in three months followed by the entire study within a year.

Six months after Hurricane Maria struck, the worst recorded natural disaster in the region, officials estimate the storm caused more than $100 billion in damages. Many on the island are still without clean water, electricity and other basic necessities.

“This study will help enhance the current methods for estimating mortality after a natural disaster.”

The number of casualties caused by the hurricane remains unclear. The government’s official toll was set at 64, but an investigation by The New York Times found that the actual number could be more than 1,000.

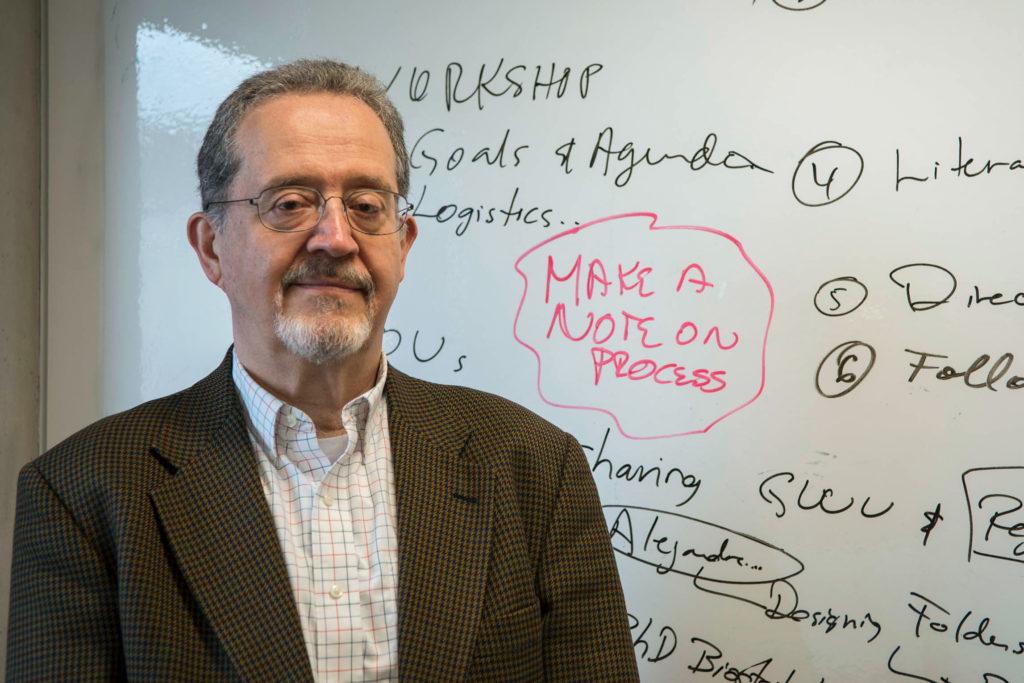

Carlos Santos-Burgoa, a global health professor and the principal investigator for the project, said he began reaching to his public health contacts at the University of Puerto Rico – a project partner – right after Hurricane Irma and Hurricane Maria damaged the island last fall.

“I have always had a relationship with Puerto Rico since I taught there many years ago, therefore it hurt me to watch the situation, desperately trying to contact friends we had there,” he said.

In December, Santos-Burgoa said a Puerto Rican professor and doctor contacted the Puerto Rican government urging them to address and define the impact of the hurricane in the midst of an emergency response that critics called chaotic.

One month later, Gov. Ricardo Rosselló Nevares of Puerto Rico signed an executive order for a more transparent account of the effects of the storm. Santos-Burgoa said Nevares wanted an external, independent group to evaluate the situation and response, selecting the public health school to conduct the inquiry.

“We accepted this project given the commitment from the government for independence and transparency. Whatever the result, we will report the findings and publish the study,” he said.

Santos-Burgoa met with Lynn Goldman, the dean of the public health school, and University President Thomas LeBlanc in the fall to discuss getting GW involved in the project. He assembled the research team in January. GW researchers are now working in tandem with a three-person research team at the University of Puerto Rico, but are still expanding the number of people assisting in the project.

Santos-Burgoa said the professors involved established the two main components of the project, first an assessment of the proper death toll and then an analysis of how the government managed counting facilities and how it communicated with island residents following the storm. The first phase of the project will cost $305,000 with funding from the Puerto Rican government and the second phase will have an estimated $1.1 million price tag, Goldman told the Washingtonian last month.

The final report will be published and presented to the Puerto Rican government and include statistics on total deaths and information on “the circumstances of each individual case.”

The report will also provide an evaluation of official communication before, during and after the hurricane to assess how well the government followed Center for Disease Control and Prevention standards for identifying post-disaster mortality. They also plan to make suggestions for improvements in future storms.

“This study will help enhance the current methods for estimating mortality after a natural disaster,” Santos-Burgoa said. “Ultimately we hope the enhanced method will allow Puerto Rico, the United States and other countries to better identify the morality impact from hurricanes and other disasters.”

“Part of preparedness for these events means there has to be a drill — you have to make a lot of decisions and it’s moving fast so mistakes happen.”

Members of the seven-person GW team include professors specializing in demography, disaster prevention and epidemiology – a medical field that examines populations at risk of health issues and diseases. Santos-Burgoa added that members were chosen based on their capacity for studying mortality and their ability to speak Spanish, which he said eliminates some cultural barriers for the study.

Amira Roess, an assistant global health professor who is working on the project, said the research the team is conducting will provide important information on the consequences – specifically mortality – that come with natural disasters.

Student involvement in the project is not off the table, Roess said.

“We will have opportunities for students to observe how data analysis for this project is completed,” she said. “Graduate students might have opportunities to participate in literature reviews and doctoral students might assist with data analysis.”

Goldman told the Washingtonian last month that the research will be a formal way to gather public health lessons from the aftermath of Maria that can be applied in the next major disaster.

“Part of preparedness for these events means there has to be a drill — you have to make a lot of decisions and it’s moving fast so mistakes happen,” she said. “The whole system is getting better at response but society and the ways in which we live are getting more complicated.”