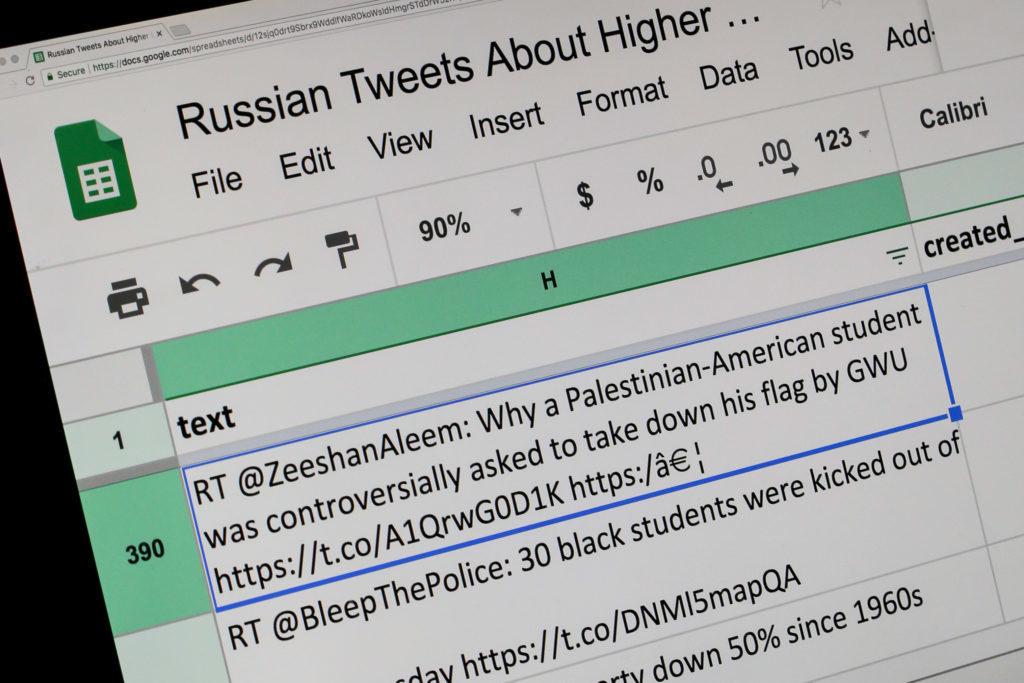

Many took interest when the University controversially asked a student to remove a Palestinian flag hanging from his residence hall room window in December 2015 – including Twitter bots linked to the Russian government.

The account @malloryjared, created by trolls who were allegedly trying to sow discord in American politics, retweeted a story that journalist Zeeshan Aleem, then a reporter at Mic, had written about the incident at GW.

But this wasn’t the only time Russia-controlled bots have taken an interest in campus events.

In an analysis of data published by The Chronicle of Higher Education, The Hatchet identified five occasions when accounts linked to Russia’s interference effort retweeted stories about incidents at GW or commentary from faculty. Experts said higher education is a prime target for those trying to create political divisions because many conservative voters are already disillusioned with more liberal college campuses.

There were 129 Twitter accounts associated with the Kremlin that tweeted and retweeted 597 messages about higher education issues between 2015 to 2017, The Chronicle found. Twitter deleted almost 200,000 tweets and suspended accounts that were tied to “malicious activity” from Russia-linked accounts during the 2016 presidential election.

Special Counsel Robert Mueller indicted 13 Russians last month who allegedly worked at a Kremlin-aligned troll farm with the aim of aggravating political tensions and advancing President Donald Trump’s campaign.

One bot account retweeted Jonathan Turley, a public interest law professor, in November 2016 when he spoke on Fox News about college student protests in the wake of Trump’s election victory. Turley spoke with then-Fox News Megyn Kelly about Trump’s victory as a repudiation of former President Barack Obama and condemned anti-Trump protests that were sprouting up in cities across the country.

“@Jonathan Turley on college protests: ‘You can’t say that you like the democratic process, but only if it comes out your way.’ #KellyFile,” Kelly tweeted that night in a post that was then retweeted by @pamela_moore13, a fake Russian account.

Turley recently wrote in a column for USA Today that he does not view Russian trolling as seriously as Russian hacking because it did not have a real impact on the American political system.

“As a columnist and commentator, it is like complaining about the weather. It is a reality of the internet and modern media,” Turley said about being retweeted by a Russian bot.

He added that it was “hardly surprising” that statements and events at GW were used by Russian trolls because students and faculty are “engaged in issues across the political spectrum.”

“The most lasting damage could prove to be the result of the ‘fixes’ rather than the original problem,” he said. “We should focus on protecting our communication and voting systems and leave the internet alone.”

Russian bots also retweeted a story about GW hiring Jesse Morton, a former member of al Qaeda as a research fellow in the Program on Extremism, a story that drew national headlines.

Morton did respond to requests to comment. He was arrested on drugs and prostitution charges in early 2017 and was fired from the University.

Another account, @sanantotopnews, shared stories about students protesting Trump’s immigration policies. While the policy did not mention any specific universities, GW students protested Trump’s immigration policies in a post-election walkout.

Conservative news outlets often pick up stories about GW. Last fall, Campus Reform filmed students who were falsely told parts of Trump’s tax plan were championed by Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt. The College Fix, another conservative publication, published an article critical of University President Thomas LeBlanc’s decision to mandate freshman diversity trainings.

John Banzhaf, a public interest law professor, said Russian accounts target universities as vehicles to create discord among groups of Americans, like white, working class Americans – most of whom did not receive a college education. Banzhaf said controversial initiatives like diversity programs and sexual assault reforms may have influenced the votes of disillusioned groups who were uncomfortable with the liberal values of many universities.

“A lot of the tweets were about campus life, diversity, immigration, sexual assault, etc. They make fun of certain things that are happening on campus, the so-called coddling of students,” he said, referring to tweets shared by propoganda bots.

Banzhaf added that Russian troll accounts used the credibility of people in academia to further their political agenda. Russian trolls used professors the same way that corporations use celebrities and athletes to sell products, he said.

“Professors get attention and also we tend to give some credence to what they say,” he said. “We tend to think of people in academia as knowledgeable and somewhat more impartial.”

Thomas Hollihan, a communication professor at the University of Southern California, said Russian troll accounts were seeking to deepen social divisions that already existed in the United States through social media. He said because universities are major holders of research data and academic materials, attacking these institutions can warp public perception of facts and news, a major goal of these accounts.

He said there is some evidence that these tactics worked in the 2016 election.

“They inflamed the situation,” he said. “They discouraged voter participation for leftists in the U.S.”