Yonah Bromberg Gaber | Graphics Editor

Despite outspending nearly all of its peer institutions on outside fundraising services in fiscal year 2016, GW raised less money than nearly all universities in its peer group, according to an analysis by The Hatchet.

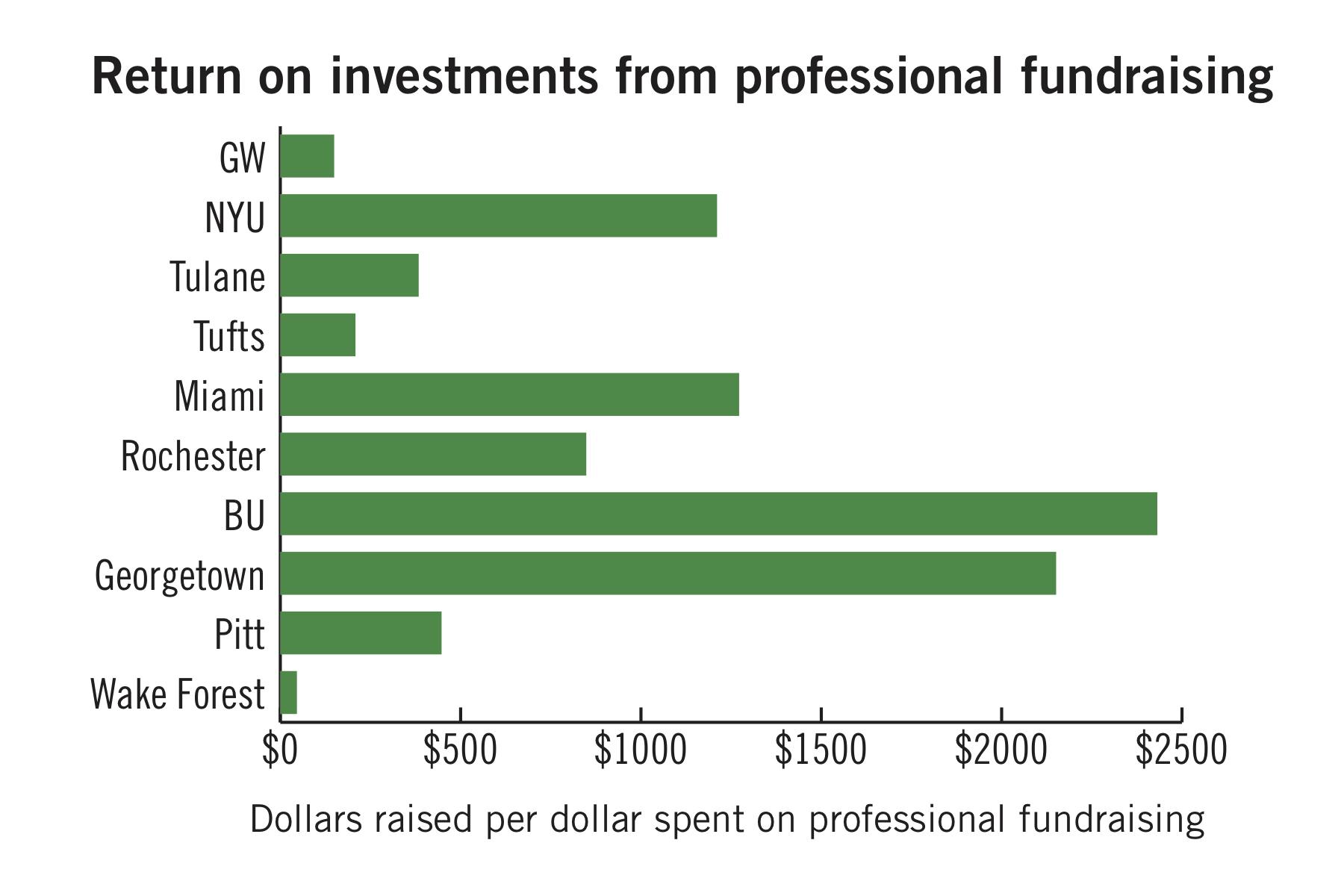

For every $1 the University shelled out for professional fundraising – services like telemarketing and advice on donor outreach – officials raised about $149 in fiscal year 2016, the most recent year for which data is available. GW’s 9 peer schools that also hired outside fundraising consultants raked in on average about six times more – $999 for every $1 spent, according to an analysis of university tax documents.

Experts said professional fundraising services are limited in helping universities attract highly coveted donations because other factors, like alumni engagement, play a much larger role in encouraging donations. GW may have spent more on outside advice than peers to help catch up with other universities that have more established traditions of alumni giving and larger fundraising operations, experts said.

GW spent more than $600,000 on professional fundraising services in fiscal year 2016 and raised more than $95 million in total, officials said. In fiscal year 2015, a more successful fundraising year, GW spent more than $1 million on outside fundraising services, according to tax documents.

Matt Manfra, the interim vice president for development and alumni relations, said professional fundraising services typically include advice on overall strategy, campaign counsel, telemarketing and gift and estate planning.

The University utilized six consulting firms in fiscal year 2016, including Heaton Smith Group and Ruffalo Noel Levitz, which were both paid more than $100,000 for their services, according to tax documents.

The outside firms helped guide the University through its $1 billion fundraising campaign – the largest in University history – that wrapped up last June, a year earlier than originally planned.

Manfra said the University has improved donor relations and that officials evaluate the return on investment rate for all of their spending, but he did not elaborate on how that data is examined.

“The University works with trusted partners who provide support for our engagement and fundraising efforts,” he said in an email. “These contract services supplement the investment the University makes in fundraising, alumni relations and advancement services staff.”

Three of GW’s 12 peer schools didn’t spend money on professional fundraising advice in the year analyzed. Syracuse University, one of the schools that didn’t hire outside firms, was the only peer university that raised less than GW that year.

Boston University raised the most per dollar spent on professional fundraising services, with a total of more than $400 million raised for a little more than $150,000 spent. Wake Forest University is the only peer school to report a worse return on investment in outside fundraising services, raising just $49 for every $1.

Manfra declined to say which professional services the University utilized and how much the University spent on professional fundraising in fiscal year 2017, when the University attracted about $117 million in donations.

University President Thomas LeBlanc announced this month at a Board of Trustees meeting that GW will use return on investment – the amount of money the University raises compared to the amount spent on development – in addition to the raw amount raised to evaluate the strength of the University’s development program.

Experts said hiring outside consultants for fundraising is a common practice across major universities that want to improve their development operations.

Ann Kaplan, the vice president of the Council for Aid to Education, an education data collecting group, said GW may be behind peers because many schools in GW’s peer group have a long tradition of alumni giving and typically outraise GW regardless of spending on outside services.

She said bringing in outside consultants is one way the University can catch up to competitors in attracting major donations, but these services take time to produce results. She said spending money on advancing telemarketing would only yield small gifts, rather than the large donations that are in high demand.

“It’s good to spend money on that because that definitely has a payoff in the large number of relatively smaller gifts,” she said. “You certainly need those because you need the base of the pyramid and you have to have that done properly.”

GW has historically struggled with a low alumni giving rate – a metric officials are trying to improve now that the $1 billion campaign has ended. The Board of Trustees created a task force last summer that will evaluate alumni engagement, and members recently announced they will continue meeting into next academic year.

GW’s alumni giving rate was at 6.8 percent in 2016, as reported by the University to CAE in a survey.

Brigitta Toth, associate director of planed giving at Washington University St. Louis, said professional fundraising services typically help universities raise more than they otherwise would have collected, but she said that advice is most beneficial for development offices with a small staff.

GW’s development office has 19 alumni relations staff and 23 advancement staff, according to its website.

“I’ve talked to someone who has one person as part of their planned giving staff,” she said.

LeBlanc has put a renewed emphasis on fundraising by hiring a new vice president for development and alumni relations, Donna Arbide, from the University of Miami.

Jessica Browning, the senior vice president of communications for the Winkler Group, a fundraising firm hired by universities like Duke, Emory, Harvard and the University of Pennsylvania, said it’s up to the schools to follow through with the consulting firm’s recommendations.

“We can give great advice,” she said. “We can walk a university down a path, but if they’re not willing to follow the recommendations of the consultant then there’s a problem.”

Alumni giving is down across the nation, she said, and consultants can help universities update and personalize their outreach to younger alumni by using new methods to connect them to a university’s fundraising office.

“Alumni giving is challenging, particularly with millenials,” Browning said. “I think universities are having a harder time engaging their alumni, especially the younger alums, because they’re using a lot of traditional methods and millennials aren’t responding to those methods.”